The Shelley Conference - London, 15-16 September 2017

On Friday and Saturday the 15th and 16th of September, in London, the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies at University of York, is presenting a two day conference that celebrates the writings of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. The event is organized by two brilliant young young Romantics scholars: Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal.

I will be speaking at this conference.

Keynote speakers include some of the very top people in this field: Professor Nora Crook, Michael Neill and Kelvin Everest. But there are also a host of panel discussions that look excellent. I strongly recommend this conference to anyone who can make it. The price is right and many of the topics are mouthwatering.

Some of the names that will be familiar to my readers include: Mark Summers who will talk about "Reclaiming Shelley's Radical Republicanism"; Anna Mercer on the extent to which Percy and Mary collaborated; Jacqueline Mulhallen on "1817 - a Philosophical Year for Shelley"; and Lynn Shepherd on "Fictionalizing the Shelleys".

As for me, my topic will be the subject of "Romantic Resistance." Shelley's writing affords modern political activists a veritable treasure trove of ideas and, as one of my readers put it, "Words of Power". As we contemplate a world in which wealth is concentrated in ever fewer hands, a world in which superstition and religion are increasing their pernicious influence, a world in which tyrants are proliferating, we must see that our world is very much Shelley's. We have need of his guidance. He was one of the greatest political thinkers of any age.

The event takes place at the Institute for English Studies, Senate House, Malet Street, London Greater London WC1E 7HU (near to the British Museum).

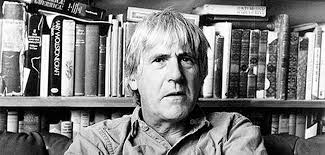

Paul Foot understood this. He persistently and passionately promoted Shelley's ideas to a generation of leftists whom he believed had lost their intellectual vigor as well as their connection to the problems of everyday people.

Paul Foot

He offered this reason for restoring Shelley to prominence: modern activists need, he said in his famous speech to the 1981 London Marxism Conference,

"...a language which has some bite and zest and enthusiasm. That’s what we have to do and that’s why I think reading great revolutionary poets like Shelley is fundamentally important. It is filled with all kinds of images, all kinds of similes and metaphors - ways of saying things, different ways of saying things. The great masters of language really understood language and could use it like great musicians use the piano. These are things we need to soak up. Particularly when those great masters of language are in line with our politics."

But I think there is more, much more, than just language. Timothy Webb once said of Shelley that “politics was probably the dominating concern of his life.” My presentation will demonstrate how Shelley’s politics, his philosophical skepticism and his theory of the imagination combine to offer some potent solutions for the troubles of the early 21st Century. Given recent events, it is time that we cast a fresh eye on romantic, specifically Shelleyan, theories of resistance.

When Shelley declared in Chamonix that he was a “lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist” he did so knowing his words would be widely read. The “Chamonix Declaration”, as I refer to it, was a more revolutionary statement than has commonly been assumed. I will offer a new interpretation of what Shelley meant by these words and the radical programme he proposed to upend the political and religious status quo.

Mont Blanc

To do this I will reopen the question of Shelley’s philosophical skepticism and the role it played in his theory of revolution. For Shelley skepticismwas a critically important tool to undermine authority and attack truth claims. In an age of “alternative facts” and “fake news” the value of skepticism as a discipline and approach to tyranny is all too evident. Mere skepticism was not and still is not, enough, however, to effect permanent political change.

I will argue that Shelley therefore evolved a theory of the imagination, at a time almost exactly contemporaneous to the Chamonix Declaration, to provide a mechanism for permanent revolutionary change; the type of change that would avoid the backsliding into chaos and tyranny he witnessed in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

Shelley has answers that remain as relevant today as they were in his time; just how we communicate those answers to the general public will also be discussed. Shelley famously wrote, "Mont Blanc yet gleams on high: the power is there," he did not mean for us to think the power lay outside us. It is actually within us all. We have the power to change the world. But we have to act. Paul Foot understood this well when he said:

Of all the things about Shelley that really inspired people since his death, the thing that matters above all is his enthusiasm for the idea that the world can be changed. It shapes all his poetry. And when you come to read Ode to the West Wind where he writes about the “pestilence stricken multitudes” and the leaves being blown by the wind; then you understand that he sees the leaves as multitudes of people stricken by a pestilence. You begin to see his ideas, his enthusiasm and his love of life. He believed in life and he really felt that life is what mattered. That life could and should be better than it is. Could be better and should be better. Could and should be changed. That was the thing he believed in most of all.

Please join me and others in London on September 14-15 for a wonderful excursion into the brilliant minds of Percy and Mary Shelley.

Shelley Square in Viareggio, Italy.