Small intro Header

BOOK REVIEWS AND RECOMENDATIONS

Will Britain Make It? The "Mask of Anarchy" is Timelier than Ever

Professor John Mullan analyses how Shelley transformed his political passion, and a personal grudge, into poetry.

Last week we drew attention to P. B. Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy as a critical social comment on class politics that is as fresh and timely today as it was when it was written two hundred years ago in 1819—and certainly no less radical. Its timeless message on the corrupt nature of political power extends into Shelley’s later “Ode to the West Wind.” While we put the Mask of Anarchy into dialogue with “Ode to the West Wind” for the latter’s emphasis on the benefits of the cross-cultural influences of globalization as a counter to the current political climate of xenophobia and myopic nationalism, Mask of Anarchy deserves a closer inspection for its critique of the nature of political authority.

Now, as then, Shelley’s poem asks us to look at the nature of order in conjunction with the dynamics of power, particularly as that power figures in political authority. Shelley wrote the poem in response to the Peterloo Massacre, a working-class uprising on 16 August 1819 at St. Peter’s Fields that sought to protest the corn laws and galvanize Parliamentary Reform to expand the voting franchise to those who did not own land. Nearly 400 were wounded and 11 died after cavalry were let loose on them, but they were ordered to do so by the local magistrates not because they were disruptive or violent. In their attempt to change politics by doing politics differently—as Shelley espouses in A Defence of Poetry—their peaceful organization was conceived as a threat. While Shelley was in Italy at the time, his distance from the events did not prevent him from acting in the only way he could—by writing a poem. Not until after 1832—when the Reform Act was passed—was the poem published, its content deemed far too radical for public eyes. The poem’s title is a multileveled metaphor that refers to a masque as a celebration of political authority, locating the poem’s critique of power alongside John Milton’s similar repudiation of the excesses of King James and Charles I’s reigns. But the word “mask” also gestures toward the way in which public figures in Shelley’s time are cloaked as actors in a medieval morality play, layering literary conventions in order to amplify the poem’s ethical message.

Will Britain, in its current state of political turmoil, make it?

Richard Carlile, Peterloo Massacre, aquatint and etching, 1819, National Portrait Gallery

If you are looking for an interesting introduction to what might be seen as one of Shelley's most radical and intensely political poems, look no further than John Mullan’s “The Mask of Anarchy.” This article is produced by the British Library as part of their "Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians" series. Professor Mullan is Professor of English at University College London and is a specialist in 18th-century literature. In 2012 he published "What Matters in Jane Austen?" I am happy link to this wonderful series because virtually all of the articles, like this one, are written in an approachable, accessible style.

From the article’s Introduction:

Percy Bysshe Shelley was living in Italy when news reached him of the Peterloo Massacre. On 16 August 1819 a crowd of well over 50,000 had gathered at St. Peter’s Fields outside Manchester to support parliamentary reform. The radical orator Henry Hunt was to speak in favour of widening the franchise and reforming Britain’s notoriously corrupt system of political representation, with its ‘pocket’ and ‘rotten’ boroughs. Magistrates ordered the Manchester Yeomanry (recruited from amongst the local middle classes) to disperse the demonstration. The cavalry charged the crowd, sabres drawn. At least 15 demonstrators, including a woman and a child, were killed, and many more wounded.

Eleanor Marx Speaks!!! The Revolutionary Percy Shelley

"We claim him as a Socialist." With these words Eleanor Marx concluded her 1888 address on the politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I strongly recommend this essay to those who want to understand the Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. Marx offers a perceptive, shrewd analysis of the political philosophy that underpinned Shelley's thought. And she offered it in 1888 at a time when English society was doing its level best to wipe out all memory of Shelley's radicalism. This happened almost exactly at the time referred to in Paul Foot's speech which you can read here.

"We claim him as a socialist" - Eleanor Marx to the Shelley Society, 1888.

Eleanor Marx with her husband Edward Aveling (R) and William Liebknecht (L). c. 1886.

With these words Eleanor Marx concluded her 1888 address on the politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I strongly recommend this essay to those who want to understand the Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. Marx offers a perceptive, shrewd analysis of the political philosophy that underpinned Shelley's thought. And she offered it in 1888 at a time when English society was doing its level best to wipe out all memory of Shelley's radicalism - a process that has continued in some quarters until this very day.

One excerpt to whet your appetite:

More than anything else that makes us claim Shelley as a Socialist is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery.

In her speech she also relays a now famous reference anecdote regarding the opinion her father had of Shelley and Byron:

The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of Socialism.

If you want to read more about Victorian attitudes to Shelley, I suggest you watch Tom Mole's presentation on his new book, What Victorians Made of Romanticism. You can buy it here. If you want to get to the crux of the issue, look no further than this brilliant encapsulation by Friedrich Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

Eleanor Marx (front centre) in 1864 with her sisters Laura and Jenny. Behind are Frederick Engels and their father Karl Marx

During these times, there was a struggle for Shelley that was fought out between what in modern terms could be called the "left" and the "right". The "hypocrites" of whom he spoke, the Victorian bourgeoisie, owned the sort of anthologies which Tom Mole talks about in his book and an engaging and accessible lecture you can watch here. Exactly who was the Shelley that the anthologies presented to the Victorian reading public? Professor Mole provides an astonishingly well researched overview of over two hundred different anthologies dating from the years 1822-1900.

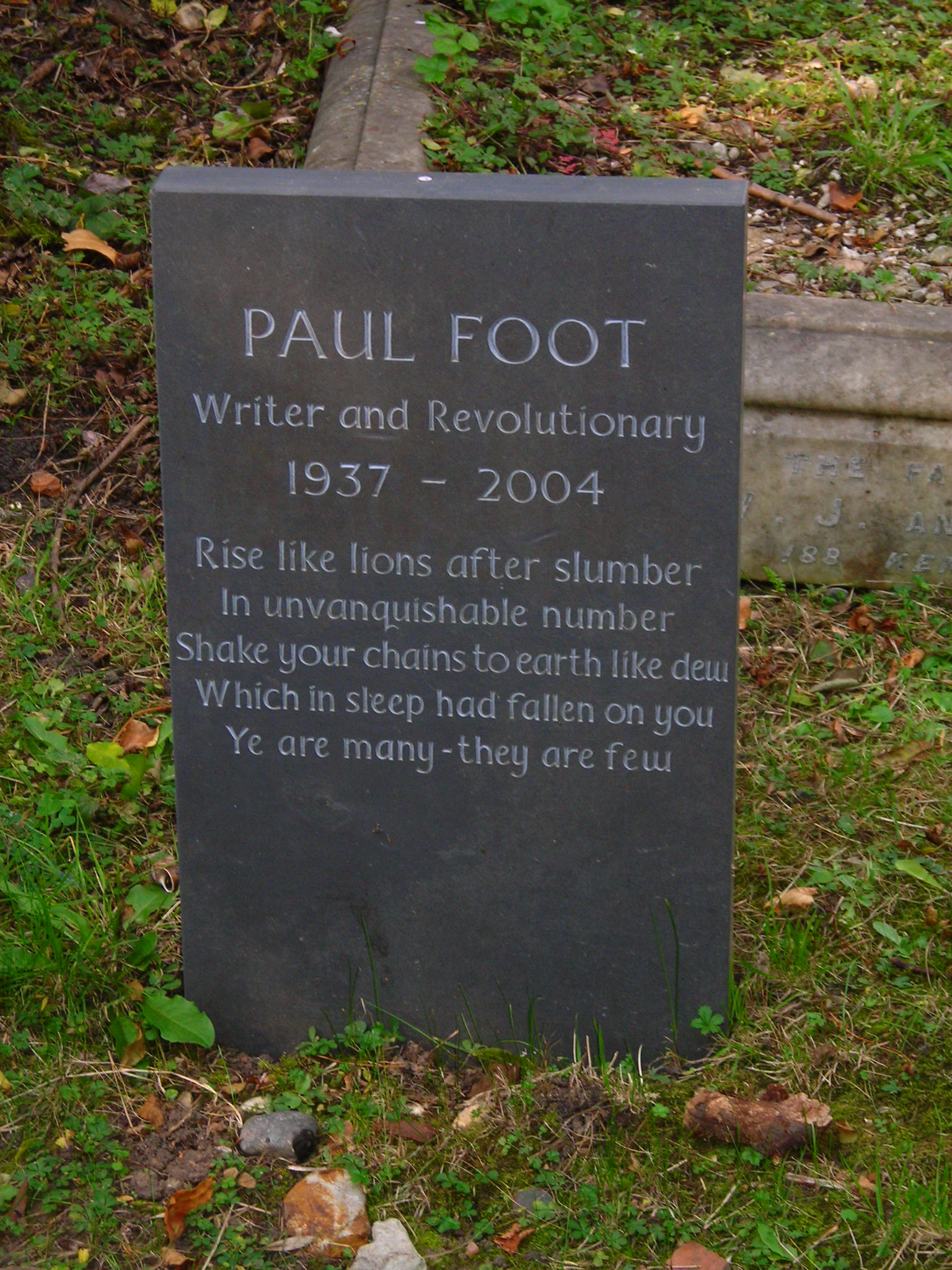

Eleanor Marx and her husband Edward Aveling delivered their speech at the height of this struggle. It was a struggle the leftists largely lost. Shelley's radicalism gradually receded from the public eye and has really never recovered despite pioneering books such as "The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical (by another Marxist, Kenneth Neil Cameron) and The Red Shelley by Paul Foot. This is not to say there was not a robust tradition on the left that continued to be inspired by Shelley. Foot was a good example of this. Reading Marx's essay it is easy to understand why Foot, the greatest crusading journalist of his generation, revered Shelley. Here is his gravestone!

Read more about Eleanor Marx here. You can also read Rachel Holmes terrific biography.

Follow this link to enjoy her speech:

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Alastor

- Alexander Larman

- Annelise Orlek

- Bram Stoker

- Byron

- Chamonix

- Ciarán O'Rourke

- Cicero

- Democracy

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Eleanor Marx

- Elinor Wylie

- England 1819

- Francis Thompson

- Frankenstein

- Gabriel Charton

- Henry Hunt

- Henry Salt

- International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Jessica Quillin

- John Keats

- John Milton

- Julius Caesar

- Larry Henderson

- Leigh Hunt

- Marixism

- Mark Andresen

- Marriage of Figaro

- Marx

- Mary Beard

- Mary Shelley

- Mask of Anarchy

- Matthew Arnold

- Michael Demson

- Michael Scrivener

- Mont Blnac

- Mulhallen

- Newman Ivey White

- Ode to Liberty

- Paradise Lost

- Paul Bond

- Paul Foot

- Paul O'Brien

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philosophical View of Reform

- PMS Dawson

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Roland Duerksen

- Ronald Tetrault

- Sandy Grant

- Song to the Men of England

- The Pan Review

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Tony Astill

- Triangle Fire

- Venetian Glass Nephew

- William Keach