Images and stories from around the world

AUDIO VISUAL PRESENTATIONS

Michael O'Neill (1953-2018) - A Brief Remembrance

Professor Michael O’Neill was a renowned poet and also one of the great modern scholars of Romanticism. No less an authority than Seamus Perry recently called him “one of our leading Shelleyan commentators.” He has died - at the dismayingly young age of 66. You can read the obituary published by the Keats Foundation here: This is a great loss and one which it will not be easy to recover from. In this, the third and final keynote of the Shelley Conference 2017, Professor Michael O’Neill takes us on an extraordinary excursion through Shelley’s prose. Alighting on works such as A Defense of Poetry, On Life, Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte, A Philosophical Review of Reform, On Christianity, and Speculations of Metaphysics, O’Neill conveys a deep and abiding knowledge and love of his subject. He offers common sense, close readings which bring Shelley alive and illustrate what he calls Shelley’s "drama of thought". The first 15 minutes set the scene and once O’Neill hits his stride with a magisterial reading of An Address to the People on the Death of Princess Charlotte, we are comfortably in the hands of a master who takes us on a tour of Shelley’s metaphysical, polemical and religious ruminations.

Michael O'Neill (1953-2018) - A Brief Remembrance

Michael O’Neill, 1952-2018

Professor Michael O’Neill was a renowned poet and also one of the great modern scholars of Romanticism. No less an authority than Seamus Perry recently called him “one of our leading Shelleyan commentators.” He has died - at the dismayingly young age of 66. You can read the obituary published by the Keats Foundation here: This is a great loss and one which it will not be easy to recover from. Personally, I did not know Michael, but I was lucky to have witnessed and recorded one of his bravura performances in 2017 at the Shelley Conference in London. One of Professor O’Neill’s greatest attributes was his ability to write and speak plainly and accessibly - unpacking often highly complex thoughts and presenting them in a simple, straightforward manner. In her touching obituary for the Keats Foundation, Heidi Thomson wrote, “above all, Michael lived for his love of poetry and he had a tremendous gift for talking about the intricacies of poetic form and poetic dynamics.“

This capacity of his was on full display that day in London when he spoke about Shelley’s use of language. I have read many books on the subject and for the most part they descend into almost impenetrable jargon from the get go. Not O’Neill. He also has a mellifluous speaking voice and could read poetry like no other. You don’t need to take my word for this - with the permission of the conference organizers I recorded it! I urge you to set aside some time to listen to one of THE great romantic scholars speaking on a subject near and dear to his heart. It will change the way you think of Percy Shelley and it will help us to keep the memory of Professor O’Neill alive.

Professor O’Neill wrote extensively in his subject area. Two of my favourite books of his are The Human Mind's Imaginings: Conflict and Achievement in Shelley's Poetry and Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Literary Life. Do yourself a favour, find these gems and spend sometime with them.

Professor O’Neill delivered the third and final keynote of the Shelley Conference 2017, and takes us on an extraordinary excursion through Shelley’s prose. Alighting on works such as A Defense of Poetry, On Life, Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte, A Philosophical Review of Reform, On Christianity, and Speculations of Metaphysics, O’Neill conveys a deep and abiding knowledge and love of his subject. He offers common sense, close readings which bring Shelley alive and illustrate what he calls Shelley’s "drama of thought". The first 15 minutes set the scene and once O’Neill hits his stride with a magisterial reading of An Address to the People on the Death of Princess Charlotte, we are comfortably in the hands of a master who takes us on a tour of Shelley’s metaphysical, polemical and religious ruminations.

Rain, Steam and Speed, JMW Turner. I think Turner's approach to his painting resonates with Shelley's approach to his poetry. Can you see how?

Professor O'Neill's keynote digs into how Shelley uses language to challenge custom and habit; or, as O’Neill puts it, to "invite [his readers] to reconsider the world in which we live." This, to me, strikes at the heart of Shelley’s entire output; this was a man who believed that poetry (or more generally cultural products) could literally change the world. I have written about this here and here.

Of great interest to me is O’Neill’s opinion that Shelley’s prose can be thought of more as poetry – or rather an amalgam of prose AND poetry. This interests me because I have often thought of his poetry as prose in disguise. For example, take the final portion of the Spirit of the Hour’s speech at the end of Act III in Prometheus Unbound. In poetic form, there are 40 lines of poetry. However, a cursory inspection reveals a startling fact: the passage is composed of only two long sentences. It is tough sledding as a performance piece. But if you render the verse into paragraph form it looks like this:

Thrones, altars, judgement-seats, and prisons; wherein, and beside which, by wretched men were borne sceptres, tiaras, swords, and chains, and tomes of reasoned wrong, glozed on by ignorance, were like those monstrous and barbaric shapes, the ghosts of a no-more-remembered fame, which, from their unworn obelisks, look forth in triumph o'er the palaces and tombs of those who were their conquerors: mouldering round, these imaged to the pride of kings and priests a dark yet mighty faith, a power as wide as is the world it wasted, and are now but an astonishment; even so the tools and emblems of its last captivity, amid the dwellings of the peopled earth, stand, not o'erthrown, but unregarded now.

And those foul shapes, abhorred by god and man, -- which, under many a name and many a form strange, savage, ghastly, dark and execrable, were Jupiter, the tyrant of the world; and which the nations, panic-stricken, served with blood, and hearts broken by long hope, and love dragged to his altars soiled and garlandless, and slain amid men's unreclaiming tears, flattering the thing they feared, which fear was hate, -- frown, mouldering fast, o'er their abandoned shrines: the painted veil, by those who were, called life, which mimicked, as with colours idly spread, all men believed or hoped, is torn aside; the loathsome mask has fallen, the man remains sceptreless, free, uncircumscribed, but man equal, unclassed, tribeless, and nationless, exempt from awe, worship, degree, the king over himself; just, gentle, wise: but man passionless? -- no, yet free from guilt or pain, which were, for his will made or suffered them, nor yet exempt, though ruling them like slaves, from chance, and death, and mutability, the clogs of that which else might oversoar the loftiest star of unascended heaven, pinnacled dim in the intense inane.

Depiction of Aias' suicide.

I believe that rendered into a prose format, the poetry scans much more easily. Try it yourself - read it aloud both ways. I think Shelley's models for this sort of speech were the classical Greek dramatists. I am thinking, for example, of some of Sophocles' lengthy speeches in, say, Aias. As an actor or reader, you must manage your way through two densely packed sentences with nested sub-clauses and hope to come out the other side alive. This is not easy. But it is easier if you convert the lines of poetry into paragraphs. Then, to my mind, the speeches flow on, beautifully and serenely - like a sylvan river! It does not surprise me to find Shelley challenging the boundaries of convention.

At the outset, O’Neill makes it clear that he is not taking us on a voyage into Shelley’s belief system – he challenges us to read him not to determine "what system of thought we can gather" from his prose or to distill "Shelley’s essential tenets", but rather "to live with the words, to see the process of the mind at work". For me, this was a novel and refreshing approach. O’Neill wants us to see "the way he uses language and see the way he delights in language". Shelley, he notes, plays with words to "free the mind from its own constructions".

My take away from this is that Shelley does not want his readers to passively absorb his prose. It is through an active engagement in unpacking his word play that Shelley expects his readers to undergo a change which is personal to them. The distilled ideas become the our own. Shelley, a skeptic to his core, is not attempting to impose any doctrinal truth upon his audience. Shelley intends that we undergo a process of imaginative transformation or reinvention – that belongs to us. I believe that this dovetails with his theory of the imagination, and I am reminded of PMS Dawson’s shrewd observation that for Shelley,

The world must be transformed in imagination before it can be changed politically, and here it is that the poet can exert an influence over “opinion.” This imaginative recreation of existence is both the subject and the intended effect of Prometheus Unbound.

As with his poetry, so it is with his prose. Shelley is asking us to read, engage and be present. Shelley expects us to reinvent ourselves and therefore the world around us because as O’Neill so trenchantly observes: "we live the lives we lead because of the thoughts we think".

Sketch of Percy Bysshe Shelley by Edward Williams. This drawing most closely resembles Leigh Hunt's late-in-life description of him.

This is why many readers find Shelley confusing. It is because words are often wrenched out of their context and applied in circumstances that are novel or counter-intuitive. He holds words up like objects to be marveled at and examined from all sides. A good example of all of this occurs in one of my favourite segments: O’Neill’s consideration of A Philosophical View of Reform which starts at 27:30.

Shelley was, as O’Neill remarks, "always battling with what he takes to be illusory or self-deceiving modes of thinking that are embodied in the language of politics". This was particularly important for Shelley because as a republican his goal was to upend the existing political order: monarchy. To accomplish his task, Shelley undertakes what O’Neill calls a "deliberative but explosive assault" on the concept of "aristocracy". Shelley asks at the outset "why an aristocracy exists at all"? He goes further and questions why we even have the very word. In what O’Neill refers to one of Shelley’s wittiest passages, Shelley goes on to define "aristocracy as that class of persons who possess a right to the labour of others without dedicating to the common service any labour in return". Shelley considers the mere existence of such a class as a "prodigious anomaly in the social system".

Shelley’s goal, it would seem, was to rob the word of its power or fascination – a goal he seems singularly (and sadly) to have failed to achieve given the fact that 200 years later England is class-ridden and burdened with a noisome, irksome, entitled aristocracy. But we can applaud him for the attempt.

Michael O’Neill is to be commended for a thrilling glimpse into the mind and heart of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I left the conference with a renewed interest in Shelley’s prose and a new method of approach. If we can approach his prose without seeking definitive philosophical statements or conclusions; then perhaps we can free our own minds from custom and habit.

Sir William Drummond. After Arminius Mayer. Hand coloured engraving, early 19th century.

I also think such an approach suits Shelley’s formal skeptical agenda. Shelley was a skeptic in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Sir William Drummond. He actually met Drummond in Rome in 1819. He read, re-read and extensively commented upon Drummond's writings during a period of time that was co-extensive with his entire philosophical output. Drummond's book, Academical Questions was his favourite work of contemporary philosophy. He was deeply suspicious of what the Greeks called doxa (“opinion”) and believed opinion to be the foundation of organized religion and therefore most of the world's woes. He advocated suspension of judgement and applied the doctrine of lack of certainty to most of his worldly interactions (in the Greek, epochê and akatalepsia, respectively). He wrote of the "prodigious depth and extent of our ignorance respecting the causes and nature of sensation". This was also tied to his political theory as he linked skepticism (which questions all dogma) with political liberty and ethical behaviour.

Professor O’Neill’s presentation will appear in a new book, Shelleyan Reimaginings and Influence: New Relations - to be issued by Oxford University Press at the beginning of March.. You can read more about it here and pre-order it.

You can also pre-order his final book of poetry, Crash and Burn; it is coming out in April.

Or, even better, ask your local bookseller to order these books for you.

Thank you Michael, you will be sorely missed and the world is much impoverished by your departure.

This presentation of Professor Michael O'Neill's keynote was done with both his permission and that of the Shelley Conference 2017. Michael was a Professor of English at Durham University. He was Head of Department from 1997 to 2000 and from 2002 to 2005. From 2005-11, he was a Director (Arts and Humanities) of the Institute of Advanced Study (IAS) at Durham University; he served as the Acting Executive Director of the IAS from January 2011 until May 2012. He is a Founding Fellow of the English Association, on the Editorial Boards of the Keats-Shelley Review, Romantic Circles, Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, Romanticism, The Wordsworth Circle, and CounterText, Chair of the International Byron Society's Advisory Board and Chair of the Wordsworth Conference Foundation. In 2005 he established and was Director of an intra-departmental research group working on Romantic Dialogues and Legacies. He has written many books on Shelley, including The Oxford Handbook of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Literary Life and The Human Mind's Imaginings: Conflict and Achievement in Shelley's Poetry. Read more about him here.

Background on The Shelley Conference

What follows is an edited version of the CFP prepared by conference organizer, Anna Mercer for The Shelley Conference 2017. You can read the original version here.

On 14 and 15 of September 2017 a two-day conference in London, England celebrated the writings of two major authors from the Romantic Period: Percy Bysshe Shelley (PBS) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (MWS).

There is a continuing scholarly fascination with all things 'Shelley' which is due in part to the

unprecedented access we now have to their texts (in annotated scholarly editions) and manuscripts (presented in facsimile and transcript). The Shelleys' works are more readily available than ever before. However somewhat disturbingly, there is no annual or even semi-regular conference dedicated to PBS (comparable to those that exist for other Romantic writers). It was this fact that prompted Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal to organise The Shelley Conference 2017.

Shockingly, it has taken almost 200 years for detailed, comprehensive editions of PBS's works to appear. I believe he is the only major poet in the English literary canon to be so woefully under served. However, two editions are nearing completion: The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook; and The Poems of Shelley edited Kelvin Everest, G.M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan. There is much, therefore, to celebrate. In addition there is the astonishing Shelley-Godwin Archive which will provide, according to the website, "the digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft, bringing together online for the first time ever the widely dispersed handwritten legacy of this uniquely gifted family of writers." It must be seen to be believed.

Conferences at Gregynog in 1978, 1980, and 1992 and the Percy Shelley Bicentennial Conference in New York in 1992 have provided a wonderful legacy for future Shelleyan academics, and it is in the spirit of these events The Shelley Conference 2017 was undertaken. MWS is included in this new conference, as she also does not have her own regular academic event. However, the recent conference 'Beyond Frankenstein's Shadow' (Nancy, France, 2016) focused specifically on MWS, and the emphasis placed on her work at the 'Summer of 1816' conference (Sheffield, 2016) indicated that her role on the main stage of Romanticism is increasingly appreciated.

It is for these reasons that the 'Shelley' of the conference title was left ambiguous. The Shelleys are increasingly seen as a collaborative literary partnership, and modern criticism reinforces the importance of reading their works in parallel. The nuances of this, however, are far from simple, and this statement does not imply there is anything like a sense of either consistent 'unity' or 'conflict' when considering the Shelleys' literary relationship. This is the kind of issue which was explored at The Shelley Conference 2017 by speakers such as the legendary Nora Crook.

Multiple parallel panel sessions allowed the organizers to present a wide range of exciting papers delivered by researchers from the UK, Europe, and beyond, as well as three featured presentations by eminent Shelley scholars: Kelvin Everest, Nora Crook and Michael O'Neill. These are some of the "superstars" of the Shelleyan world.

A City of Death: The Shelleys and Mont Blanc

In September of 2017 "The Shelley Conference" took place in London, England. It brought together some of the greatest Shelleyans alive, and it introduced to the world a new generation of young scholars brimming with interesting ideas about Mary and Percy. Carl McKeating is one of those young scholars. Carl introduces some startling insights into what and who shaped the impressions the Shelley's formed of Mont Blanc and its environs. Those impressions were to influence some of the most important literature in the western canon: Percy's poem, Mont Blanc and Mary's novel, Frankenstein. Please join Carl for a thrilling, insightful 20 minute excursion to Chamonix in 1816!

Graham with Mont Blanc in the background, 2016.

One of the genuine highlights of the Shelley Conference 2017 was a dynamic presentation by University of Leeds scholar Carl McKeating: "A City of Death: The Shelleys and Mont Blanc." Taking Mary and Percy’s History of a Six Weeks Tour as his focus, McKeating explores what was for me an exciting but hitherto poorly understood aspect of the book: the extent to which Mary’s and Percy’s perceptions of Mont Blanc were influenced and even conditioned by the tour guides they employed.

Carl McKeating.

When I met Carl at the Shelley Conference 2017, I was delighted to discover that we shared a love of the mountains and rock climbing. He has even authored books and articles on the subject. You can learn more about him here. Of his experiences, Carl writes,

I feel my research benefits from the insight offered by a climbing and mountaineering background. I have had a varied career that for the most part has prioritised spending time in mountain ranges. Nonetheless, I momentarily settled down to teach and left my most recent post as a secondary English teacher to commence the PhD at Leeds. I studied at Lancaster University for my undergraduate degree, where the tutorship of the poet Paul Farley was an inspiration for future academic and creative writing.

But before getting to McKeating's great talk (included in audio-visual below), I wanted set the scene a little and share some of my own experiences with a mountain that in some ways can feel a bit anti-climactic after having read all the great literature about it. So, buckle up: we're headed to the Alps!

Mont Blanc seen from Geneva. Copyright Graham Henderson, 2016.

The photograph above provides a view of the Mont Blanc Massif that is identical to that which the Shelleys might have enjoyed from their window in the Hotel d'Angleterre. I say might because the summer the Shelleys spent in Switzerland came to be known as the "Year Without Summer." Cold, dark, rainy - even snowy - the summer of 1816 was exceptionally bad. The unseasonable weather was attributable to a combination of factors. Europe was still in the grips of what today we call the "little ice age". But the conditions were exacerbated by the eruption in 1815 of a massive volcano, Mount Tambora. You can read about it here. It is more likely that the Shelley's saw something like this (perhaps minus the dramatic rainbow!):

View of Mont Blanc Massif, obscured by clouds. Copyright Graham Henderson, 2016.

If you travel to Mont Blanc today, you will have a very different experience from that of the Shelleys, who described the famous Swiss mountain as sublime and infused with supernatural terrors. Today, you can leave Geneva on a modern superhighway and be in your hotel room in just over an hour. Mary and Percy's journey required almost three days on horseback.

If you wanted to avoid the superhighways and follow the footsteps of the Shelleys instead, you follow the old “Imperial Highway” which takes you through Servox (not shown on the map above). The first part of the journey is through wide open, picturesque countryside with no hint of sublimity. Here is what it would have looked like to the Shelleys when they reached the environs of Bonneville just south of Geneva:

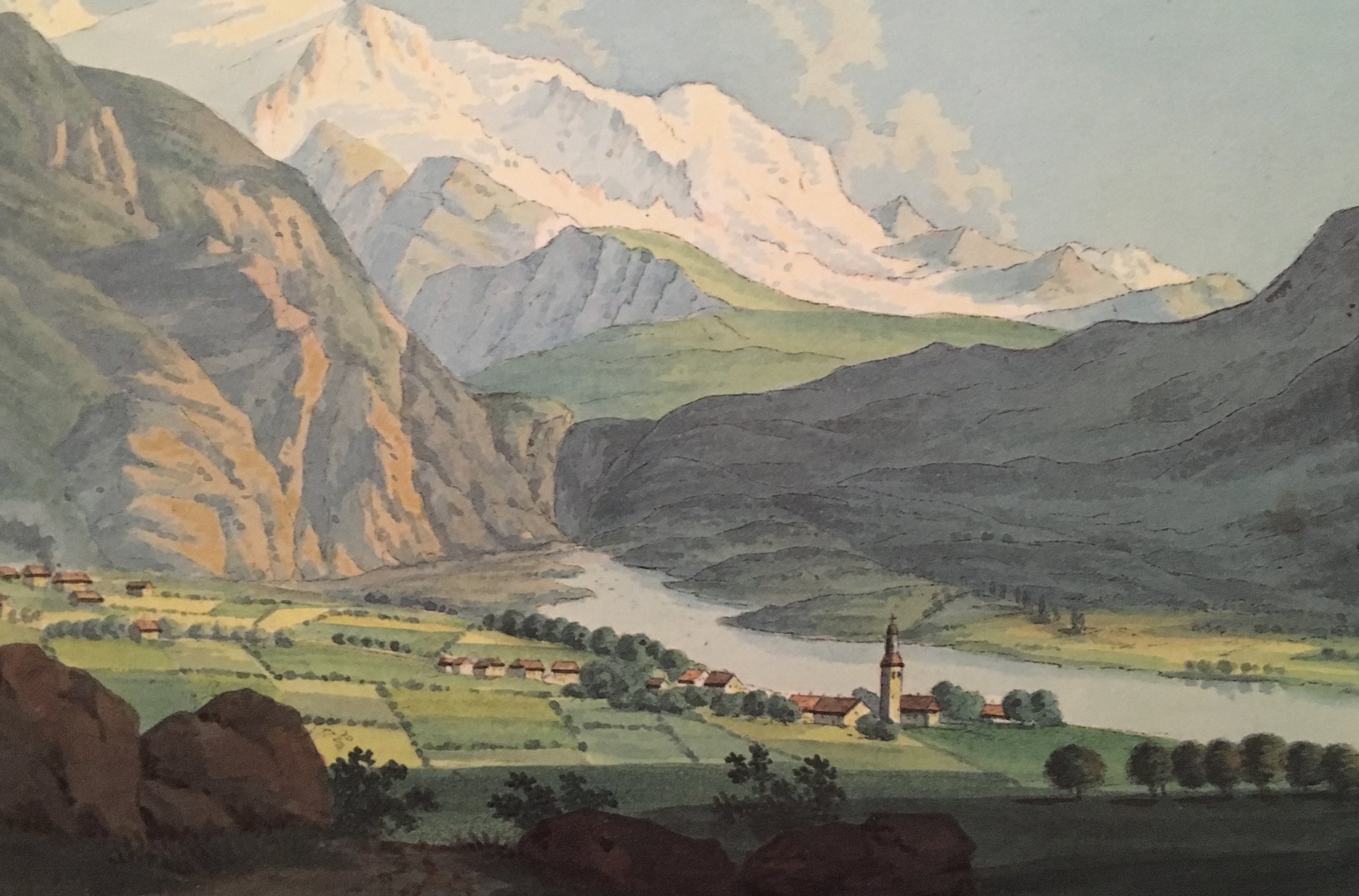

Gabriel Charton, "Saint-Martin". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015

However, the further you go, the more intimations there are of what is to come. For example, I stopped near Oex and walked to the base of the Cascade de l'Arpenaz. Percy Shelley wrote about this place in his letter to Thomas Love Peacock on 22 July 1816. You should carefuly compare it with the image to the right to see how startling accurate Percy's description is:

Cascade de l'Arpenaz. Copyright Henderson

"They were no more than mountain rivulets, but the height from which they fell, at least of twelve hundred feet, made them assume a character inconsistent with the smallness of their stream. The first [i.e. the Arpenaz waterfall] fell from the overhanging brow of a black precipice on an enormous rock, precisely resembling some colossal Egyptian deity. It struck the head of the visionary image, and gracefully dividing there, fell from it in folds of foam more like to cloud than water, imitating a veil of the most exquisite woof. It then united, concealing the lower part of the statue, and hiding itself in a winding of its channel, burst into a deeper fall, and crossed our route in its path towards the Arve."

From there I continued on the Imperial Highway to Servoz. The road climbs up on the shoulder of the valley north of the ravine, reaching a considerable height at Servoz which today is a gorgeous little village where properties are on sale for almost USD $2,000,000. When Shelley visited, it was little more than a hamlet. After Servoz, the road then descends to the valley floor and the valley narrows dramatically. It would have looked like this to Shelley. You can see the ravine of the Arve in the middle distance:

Gabriel Charton, "Servox". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015. The church is still there.

Shortly after you enter this gorge, the river suddenly (and famously) makes a sharp turn to the left which dramatically reveals the Mont Blanc Massif in all of its majesty. Here is what Shelley wrote:

"As we proceeded, our route still lay through the valley, or rather, as it had now become, the vast ravine, which is at once the couch and the creation of the terrible Arve. We ascended, winding between mountains whose immensity staggers the imagination. We crossed the path of a torrent, which three days since had descended from the thawing snow, and torn the road away... From Servoz three leagues remain to Chamouni.—Mont Blanc was before us—the Alps, with their innumerable glaciers on high all around, closing in the complicated windings of the single vale—forests inexpressibly beautiful, but majestic in their beauty—intermingled beech and pine, and oak, overshadowed our road, or receded, whilst lawns of such verdure as I have never seen before occupied these openings, and gradually became darker in their recesses. Mont Blanc was before us, but it was covered with cloud; its base, furrowed with dreadful gaps, was seen above. Pinnacles of snow intolerably bright, part of the chain connected with Mont Blanc, shone through the clouds at intervals on high. I never knew—I never imagined what mountains were before. The immensity of these aerial summits excited, when they suddenly burst upon the sight, a sentiment of extatic wonder, not unallied to madness. And remember this was all one scene, it all pressed home to our regard and our imagination. Though it embraced a vast extent of space, the snowy pyramids which shot into the bright blue sky seemed to overhang our path; the ravine, clothed with gigantic pines, and black with its depth below, so deep that the very roaring of the untameable Arve, which rolled through it, could not be heard above—all was as much our own, as if we had been the creators of such impressions in the minds of others as now occupied our own. Nature was the poet, whose harmony held our spirits more breathless than that of the divinest."

When I arrived in the valley, I encountered the same problem that bedeviled the Shelleys -- Mont Blanc was shrouded with clouds.

The Vale of Chamonix, 2016. Copyright Henderson.

One thing that the modern traveler misses is the thundering of the Arve. The modern roads are far removed from the river and the roar of traffic obscures that of the river itself. One other thing I can tell you is this – pictures do the valley absolutely no justice whatsoever. No picture I have ever seen conveys the manner in which the mountains seem to, as Shelley notes, “overhang” the valley floor. Here is a contemporary painting which offers a view the Shelleys would not have seen because they did not travel to the Col de Voza:

Gabriel Charton, "Le Col de Voza." From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015

Mont Blanc is not even in the picture; it is off to the right. In the foreground, you can see the Glacier des Bossons. Just beyond it lies the spire of the church in Chamonix and then the terminus of the Mer de Glace, which you can see actually encroaches on the valley floor itself. Today these glaciers have long since receded into the mountains.

It is a point worth making that for travelers in the early 19th century, even for those such as the Shelleys who had never seen the Alps, there is an aura of the picturesque that infuses the valley – not the sublime. In other words, the landscape around Mont Blanc is ruggedly beautiful, rather than overwhelmingly powerful, a quality we do find in Shelley's great poem "Mont Blanc." While they were in the valley, the Shelleys had difficulty actually seeing Mont Blanc – and this is not at all unusual. A cloud deck seems to perpetually overhang the valley. But even when you can see it, the mountain is not exactly imposing in-and-of-itself. Here is a photo I took a couple of years back that will give you a better idea of this:

Mont Blanc Massif from Chamonix. Copyright Henderson, 2016.

Mont Blanc is not the sharp peak the left. Nor is it the one on the right. In fact, it is the subtle summit set back from the rest almost dead center of the photograph. Trust me, it does not in-and-of-itself inspire the feelings of awe and dread we encounter in Shelley's poem bearing the mountain's name. It is not at all evident that it is even the tallest mountain. In fact, the reverse seems to be true. The Aguile de Midi looms precipitously above your head in Chamonix – Mont Blanc is a distant and altogether benign presence. Not like Mount Everest, for example. I have stood at North Face Base Camp – and let me tell you, up close Mount Everest looks like a stone-cold killer:

North Face of Mount Everest from Rongbuk. Copyright Henderson, 1994.

There is no doubt that the Shelleys’ minds would have been very much more impressionable than ours are today – and less inured to wild landscapes. They had never actually seen real mountains. Very few travel guides existed that could prepare you for what you were about to see. As I mentioned before, in the 1810s, the Mont Blanc glaciers actually spilled out onto the valley and were menacingly advancing (for an idea of how this might have looked to the Shelleys, see the image below). The Shelleys were also fresh from their stay at the Villa Diodati where they had engaged in a ghost-story competition! Then there was the outlandish weather that was the hallmark of the “Year Without Summer”. All of this may well have perhaps primed then for, shall we say, a heightened experience.

Gabriel Charton, "La Source de l'Arvenon". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015.

The glacier can not even be seen from Montanvert. It is around the corner having retreated 10 miles thanks to climate change- why am I smiling!? Copyright Henderson, 2016.

This leaves us with an obvious dilemma: if the mountain is somewhat unremarkable, why do the Shelleys write about it as if it were the most imposing, threatening presence in the Alps? This is where Carl McKeating picks up the story, for as he tells us, there was another factor which led to the Shelley’s highly emotional response to what they saw: they were powerfully influenced by their tour guides. As McKeating points out, critics have rarely viewed the Shelleys as tourists, but this is exactly what they were. In fact, in several instances, Percy bluntly complains about the presence of other tourists – demonstrating that the more things change, the more they stay the same!

Both Mary and Percy frame Mont Blanc as a place where supernatural forces lurked and where death was imminent. References to Mont Blanc as the abode of witches appears in Byron’s Manfred, Mary’s Frankenstein and Percy’s "Mont Blanc." Percy at one point records witnessing an avalanche -- in July 1816. McKeating speculates on the role the guides might have played at such a moment. While their duty was to keep the guests safe, they also wanted to take tourists to the most exciting places – places which also might involve an experience of danger.

The guides also regaled their charges with folklore and wild tales. McKeating suggests that much of what we read in the accounts of Mary and Percy is derived directly from stories they were told. Mary often begins an episode with the words, “our guide told us a story….”

McKeating also notes how Percy’s impression of Mont Blanc radically evolved over an extremely short period of time. Before he left, Percy had written to Byron referring to the mountains as “palaces of nature.” By the time he wrote about them in his great poem, they had become “palaces of death.”

McKeating is also one of the most entertaining presenters I have ever seen inside or outside of the academy. You will thank me if you take my advice and spend 20 minutes with him while he spins his own tale of mystery, intrigue, witches......and the palace of death!!!

You can visit Carl's profile here. And this is an overview of the research Carl is undertaking at the University of Leeds:

Mont Blanc was a towering presence in the imaginative geography of British eighteenth and early nineteenth century writing, featuring in poetry, fiction, travel literature, and natural philosophy. My work uses a broadly chronological and geocritical approach to investigate the cultural prominence of Western Europe's highest mountain. The period of my study addresses the 'discovery' of Mont Blanc by William Windham's party of 'Eight Englishmen' in 1741, Mont Blanc's first ascent by the Horace Benedict de Saussure-sponsored Paccard and Balmat in 1786, and the mountain's literary blossoming during the Romantic period when it played a key role in the re-evaluation of mountain topography and the formation of identity for British writers including William Wordsworth, Helen Maria Williams, Mary Robinson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

What the Victorians Made of Shelley. By Tom Mole

In September at the London Shelley Conference 2017 I had the pleasure of listening to an expert, Professor Tom Mole, speak about one of my favourite subjects: what Victorians thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. This is actually an extremely important question, because what the Victorians thought about Shelley set the tone for succeeding generations of readers and critics. They played a crucial and controversial role in the transmission of Shelley's poetry to the modern era. Professor Mole has done Shelleyans a great service.

Visit my Shelley blog! www.grahamhenderson.ca

Introduction

In September at the London Shelley Conference 2017 I had the pleasure of listening to an expert, Professor Tom Mole, speak about one of my favourite subjects: what Victorians thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. A link to the speech is provided below.

I have written at length about this myself including here: "My Father's Shelley - A Tale of Two Shelleys". This is actually extremely important because what the Victorians thought about Shelley set the tone for succeeding generations of readers and critics. They played a crucial and controversial role in the transmission of Shelley's poetry to the modern era.

There have been many treatments of this subject. But to set the scene, it is important to remember that Shelley was not very well known in his own time. Shortly after he died Mary prepared a slim volume called "Posthumous Poems" which presented a very different Shelley from the one that lived and breathed. She gave the world a poet who was a far cry from the radical revolutionary who died in 1822. It was the beginning of a tradition of misrepresentation that has continued almost to this day. My views on this have been recently tempered by the brilliant Nora Crook, whose presentation on the question of Mary's editing of Shelley can be seen here. Other views appear in Michael Gamer's wonderful book, "Romanticism, Self-Canonization, and the Business of Poetry". You can buy it here. Then there is a wonderful book by one of the most underrated Shelley scholars of all time, Roland Duerksen: "Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature."

If you want to get to the crux of the issue, look no further than this brilliant encapsulation by Frederich Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

During these times, there was a struggle for Shelley that was fought out between what in modern terms could be called the "left" and the "right". The "hypocrites" of whom he spoke, the Victorian bourgeoisie, owned the sort of anthologies which Tom Mole talks about in this wonderful, engaging and accessible lecture. Exactly who was the Shelley that the anthologies presented to the Victorian reading public? Professor Mole provides an astonishingly well researched overview of over two hundred different anthologies dating from the years 1822-1900. He has saved us all the trouble!

in his book, Mole did not just focus on Shelley, but he does so in his speech. The anthologies of which he speaks were, he writes, "magic casements" that showcased the "oceanic breadth of romantic poetry, while at the same time framing and limiting the readers view of it." This matters because Shelley was a poet who set out to change the world. As he wrote to Leigh Hunt once, “I am undeceived in the belief that I have powers deeply to interest, or substantially improve, mankind.” An intensely political individual, I think Shelley would have been horrified to have been presented to the reading public - many of whom would have been from the proletariat - as a lyric love poet.

But as Mole demonstrates, the anthologists favoured his short lyrics over his longer more political poems. When they did turn to his longer poetry, they had tricky choices to make. Poems like Queen Mab, The Cenci and Alastor were clearly associated with subversive political themes which the bourgeoisie had absolutely no interest in showcasing. The solution was to focus on what Mole calls "passages of isolated description" which, he notes, is "exactly what Shelley sought to avoid."

The pickings were thin, but the anthologists were nothing if not dedicated to their task. Mole walks of through three examples from the aforementioned poems. The most popular excerpt from Queen Mab was a descriptive section: lines 420-449. Mole points out that the passage selected, presents a lyrical, sylvan environment free from "narrative, tension and decay." In other words the exact opposite of what Shelley would have wanted a reader to encounter. We have to remember that during the period immediately after his death, Chartists and other radicals were gorging themselves on the radicalism of Queen Mab - to thus drain it of its political foundations was a grotesque misappropriation.

Mole does make the point that Victorian anthologies nonetheless circulated what amounted to links to the subversive substrata that existed beyond their pages. For my part I think the damage that was done far outweighs this modest gain. Even today those of us inspired by Shelley's radicalism, for example Paul Foot, must wrestle with the legacy of misdirection these incredibly influential anthologies left behind. To here Foot on the subject, please read the entirety of his speech to the London Marxism Conference of 1981 here.

I, however, have said enough - let's turn our attention to Professor Mole!!! You will thoroughly enjoy his presentation.

About Tom Mole

Tom Mole is Reader in English Literature and Director of the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. He studied at the University of Bristol and has worked at the University of Glasgow, the University of Bristol and, most recently, as Associate Professor and William Dawson Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. You can find him on Twitter here. Tom's website is here. Read more about his new book here.

About Tom's Book

"This insightful and elegantly written book examines how the popular media of the Victorian era sustained and transformed the reputations of Romantic writers. Tom Mole provides a new reception history of Lord Byron, Felicia Hemans, Sir Walter Scott, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Wordsworth--one that moves beyond the punctual historicism of much recent criticism and the narrow horizons of previous reception histories. He attends instead to the material artifacts and cultural practices that remediated Romantic writers and their works amid shifting understandings of history, memory, and media. Mole scrutinizes Victorian efforts to canonize and commodify Romantic writers in a changed media ecology. He shows how illustrated books renovated Romantic writing, how preachers incorporated irreligious Romantics into their sermons, how new statues and memorials integrated Romantic writers into an emerging national pantheon, and how anthologies mediated their works to new generations. This ambitious study investigates a wide range of material objects Victorians made in response to Romantic writing--such as photographs, postcards, books, and collectibles--that in turn remade the public's understanding of Romantic writers. Shedding new light on how Romantic authors were posthumously recruited to address later cultural concerns, What the Victorians Made of Romanticism reveals new histories of appropriation, remediation, and renewal that resonate in our own moment of media change, when once again the cultural products of the past seem in danger of being forgotten if they are not reimagined for new audiences."

From the Back Cover!

"This ambitious book is a major contribution to our understanding of Romanticism, not only what it was but also what it became. It will be an essential guide to the web of reception and remaking for period specialists, while also posing urgent questions--and answers--for our own moment of hypermediation."--Clifford Siskin, New York University

"What have Victorian temperance lectures to do with Shelley, retrofitted illustrations to say about Wordsworth, or snuffboxes and postcards to tell us about Scott? In fascinating case studies, Tom Mole traces the unexpected shapes that literature is requisitioned to fill in the interests of its own survival. Mole writes with relish and flair, and with a canny awareness that these are the stories of what happens as texts and reputations are remade and reused for more purposes than those of the professional critic."--Kathryn Sutherland, University of Oxford

"Original and compelling. What the Victorians Made of Romanticism presents a number of valuable insights and perspectives on its topic."--Antony H. Harrison, author of Victorian Poets and Romantic Poems: Intertextuality and Ideology

"Convincing and nuanced. Mole extends existing knowledge of the Victorian reshaping of Romanticism by tracing the cultural transmission of selected Romantic poets through often overlooked reception practices such as sermons, illustrations, anthologies, and statues."--Kim Wheatley, author of Romantic Feuds: Transcending the "Age of Personality"

"A splendid book. Mole provides a much needed perspective on how the broader culture of the Victorian age responded to a highly selective and heavily mediated and remediated version of Romanticism."--David G. Riede, author of Matthew Arnold and the Betrayal of Language

Background on the Shelley Conference 2017

What follows is an edited version of the CFP prepared by conference organizer, Anna Mercer for The Shelley Conference 2017. You can read the original version here.

On 14 and 15 of September 2017 a two-day conference in London, England celebrated the writings of two major authors from the Romantic Period: Percy Bysshe Shelley (PBS) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (MWS).

There is a continuing scholarly fascination with all things 'Shelley' which is due in part to the

unprecedented access we now have to their texts (in annotated scholarly editions) and manuscripts (presented in facsimile and transcript). The Shelleys' works are more readily available than ever before. However somewhat disturbingly, there is no annual or even semi-regular conference dedicated to PBS (comparable to those that exist for other Romantic writers). It was this fact that prompted Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal to organise The Shelley Conference 2017.

Shockingly, it has taken almost 200 years for detailed, comprehensive editions of PBS's works to appear. I believe he is the only major poet in the English literary canon to be so woefully under served. However, two editions are nearing completion: The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook; and The Poems of Shelley edited Kelvin Everest, G.M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan. There is much, therefore, to celebrate. In addition there is the astonishing Shelley-Godwin Archive which will provide, according to the website, "the digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft, bringing together online for the first time ever the widely dispersed handwritten legacy of this uniquely gifted family of writers." It must be seen to be believed.

Conferences at Gregynog in 1978, 1980, and 1992 and the Percy Shelley Bicentennial Conference in New York in 1992 have provided a wonderful legacy for future Shelleyan academics, and it is in the spirit of these events The Shelley Conference 2017 was undertaken. MWS is included in this new conference, as she also does not have her own regular academic event. However, the recent conference 'Beyond Frankenstein's Shadow' (Nancy, France, 2016) focused specifically on MWS, and the emphasis placed on her work at the 'Summer of 1816' conference (Sheffield, 2016) indicated that her role on the main stage of Romanticism is increasingly appreciated.

It is for these reasons that the 'Shelley' of the conference title was left ambiguous. The Shelleys are increasingly seen as a collaborative literary partnership, and modern criticism reinforces the importance of reading their works in parallel. The nuances of this, however, are far from simple, and this statement does not imply there is anything like a sense of either consistent 'unity' or 'conflict' when considering the Shelleys' literary relationship. This is the kind of issue which was explored at The Shelley Conference 2017 by speakers such as the legendary Nora Crook.

“We Live the Lives We Lead Because of the Thoughts We Think”

In this, the third and final keynote of the Shelley Conference 2017, Professor Michael O’Neill takes us on an extraordinary excursion through Shelley’s prose. Alighting on works such as A Defense of Poetry, On Life, Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte, A Philosophical Review of Reform, On Christianity, and Speculations of Metaphysics, O’Neill conveys a deep and abiding knowledge and love of his subject. He offers common sense, close readings which bring Shelley alive and illustrate what he calls Shelley’s "drama of thought". The first 15 minutes set the scene and once O’Neill hits his stride with a magisterial reading of An Address to the People on the Death of Princess Charlotte, we are comfortably in the hands of a master who takes us on a tour of Shelley’s metaphysical, polemical and religious ruminations.

In this, the third and final keynote of the Shelley Conference 2017, Professor Michael O’Neill takes us on an extraordinary excursion through Shelley’s prose. Alighting on works such as A Defense of Poetry, On Life, Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte, A Philosophical Review of Reform, On Christianity, and Speculations of Metaphysics, O’Neill conveys a deep and abiding knowledge and love of his subject. He offers common sense, close readings which bring Shelley alive and illustrate what he calls Shelley’s "drama of thought". The first 15 minutes set the scene and once O’Neill hits his stride with a magisterial reading of An Address to the People on the Death of Princess Charlotte, we are comfortably in the hands of a master who takes us on a tour of Shelley’s metaphysical, polemical and religious ruminations.

Professor O'Neill's keynote digs into how Shelley uses language to challenge custom and habit; or, as O’Neill puts it, to "invite [his readers] to reconsider the world in which we live." This, to me, strikes at the heart of Shelley’s entire output; this was a man who believed that poetry (or more generally cultural products) could literally change the world. I have written about this here and here.

Rain, Steam and Speed, JMW Turner. I think Turner's approach to his painting resonates with Shelley's approach to his poetry. Can you see how?

Of great interest to me is O’Neill’s opinion that Shelley’s prose can be thought of more as poetry – or rather an amalgam of prose AND poetry. This interests me because I have often thought of his poetry as prose in disguise. For example, take the final portion of Spirit of the Hour’s speech at the end of Act 3 in Prometheus Unbound. In poetic form, there are 40 lines of poetry. Rendered in paragraph form it looks like this:

Thrones, altars, judgement-seats, and prisons; wherein, and beside which, by wretched men were borne sceptres, tiaras, swords, and chains, and tomes of reasoned wrong, glozed on by ignorance, were like those monstrous and barbaric shapes, the ghosts of a no-more-remembered fame, which, from their unworn obelisks, look forth in triumph o'er the palaces and tombs of those who were their conquerors: mouldering round, these imaged to the pride of kings and priests a dark yet mighty faith, a power as wide as is the world it wasted, and are now but an astonishment; even so the tools and emblems of its last captivity, amid the dwellings of the peopled earth, stand, not o'erthrown, but unregarded now. And those foul shapes, abhorred by god and man, -- which, under many a name and many a form strange, savage, ghastly, dark and execrable, were Jupiter, the tyrant of the world; and which the nations, panic-stricken, served with blood, and hearts broken by long hope, and love dragged to his altars soiled and garlandless, and slain amid men's unreclaiming tears, flattering the thing they feared, which fear was hate, -- frown, mouldering fast, o'er their abandoned shrines: the painted veil, by those who were, called life, which mimicked, as with colours idly spread, all men believed or hoped, is torn aside; the loathsome mask has fallen, the man remains sceptreless, free, uncircumscribed, but man equal, unclassed, tribeless, and nationless, exempt from awe, worship, degree, the king over himself; just, gentle, wise: but man passionless? -- no, yet free from guilt or pain, which were, for his will made or suffered them, nor yet exempt, though ruling them like slaves, from chance, and death, and mutability, the clogs of that which else might oversoar the loftiest star of unascended heaven, pinnacled dim in the intense inane.

Depiction of Aias' suicide.

A cursory inspection reveals a starting fact: the above passage is composed of only two long sentences. It is a difficult read in poetic form, but rendered into a prose format, it scans much more easily. Try it yourself. I think Shelley's models for this sort of speech were the classical Greek dramatists. I am thinking, for example, of some of Sophocles' lengthy speeches in, say, Aias.

As an actor, you would have to manage your way through densely packed sentences with nested sub-clauses and hope to come out the other side alive. This is not easy. But it is easier if you convert the lines of poetry into paragraphs. Then, to my mind, the speeches flow on, beautifully and serenely - like a sylvan river! It does not surprise me to find Shelley challenging the boundaries of convention.

At the outset, O’Neill makes it clear that he is not taking us on a voyage into Shelley’s belief system – he challenges us to read him not to determine "what system of thought we can gather" from his prose or to distill "Shelley’s essential tenets", but rather "to live with the words, to see the process of the mind at work". For me, this was a novel and refreshing approach. O’Neill wants us to see "the way he uses language and see the way he delights in language". Shelley, he notes, plays with words to "free the mind from its own constructions".

My take away from this is that Shelley does not want his readers to passively absorb his prose. It is through an active engagement in unpacking his word play that Shelley expects his readers to undergo a change which is personal to them. The distilled ideas become the our own. Shelley, a skeptic to his core, is not attempting to impose any doctrinal truth upon his audience. Shelley intends that we undergo a process of imaginative transformation or reinvention – that belongs to us. I believe that this dovetails with his theory of the imagination, and I am reminded of PMS Dawson’s shrewd observation that for Shelley,

The world must be transformed in imagination before it can be changed politically, and here it is that the poet can exert an influence over “opinion.” This imaginative recreation of existence is both the subject and the intended effect of Prometheus Unbound.

As with his poetry, so it is with his prose. Shelley is asking us to read, engage and be present. Shelley expects us to reinvent ourselves and therefore the world around us because as O’Neill so trenchantly observes: "we live the lives we lead because of the thoughts we think".

Sketch of Percy Bysshe Shelley by Edward Williams. This drawing most closely resembles Leigh Hunt's late-in-life description of him.

This is why many readers find Shelley confusing. It is because words are often wrenched out of their context and applied in circumstances that are novel or counter-intuitive. He holds words up like objects to be marveled at and examined from all sides. A good example of all of this occurs in one of my favourite segments: O’Neill’s consideration of A Philosophical View of Reform which starts at 27:30.

Shelley was, as O’Neill remarks, "always battling with what he takes to be illusory or self-deceiving modes of thinking that are embodied in the language of politics". This was particularly important for Shelley because as a republican his goal was to upend the existing political order: monarchy. To accomplish his task, Shelley undertakes what O’Neill calls a "deliberative but explosive assault" on the concept of "aristocracy". Shelley asks at the outset "why an aristocracy exists at all"? He goes further and questions why we even have the very word. In what O’Neill refers to one of Shelley’s wittiest passages, Shelley goes on to define "aristocracy as that class of persons who possess a right to the labour of others without dedicating to the common service any labour in return". Shelley considers the mere existence of such a class as a "prodigious anomaly in the social system".

Shelley’s goal, it would seem, was to rob the word of its power or fascination – a goal he seems singularly (and sadly) to have failed to achieve given the fact that 200 years later England is class-ridden and burdened with a noisome, irksome, entitled aristocracy. But we can applaud him for the attempt.

Michael O’Neill is to be commended for a thrilling glimpse into the mind and heart of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I left the conference with a renewed interest in Shelley’s prose and a new method of approach. If we can approach his prose without seeking definitive philosophical statements or conclusions; then perhaps we can free our own minds from custom and habit. As O’Neill reminds us: "we live the lives we lead because of the thoughts we think".

I also think such an approach suits Shelley’s formal skeptical agenda. Shelley was a skeptic in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Sir William Drummond. He actually met Drummond in Rome in 1819. He read, re-read and extensively commented upon Drummond's writings during a period of time that was co-extensive with his entire philosophical output. Drummond's book, Academical Questions was his favourite work of contemporary philosophy. He was deeply suspicious of what the Greeks called doxa (“opinion”) and believed opinion to be the foundation of organized religion and therefore most of the world's woes. He advocated suspension of judgement and applied the doctrine of lack of certainty to most of his worldly interactions (in the Greek, epochê and akatalepsia, respectively). He wrote of the "prodigious depth and extent of our ignorance respecting the causes and nature of sensation". This was also tied to his political theory as he linked skepticism (which questions all dogma) with political liberty and ethical behaviour.

I understand that Michael O’Neill’s presentation will appear in a new book soon to be issued by Oxford University Press. In the meantime, we have his wonderful keynote to enjoy and treasure for all time, thank you Michael!

This presentation of Professor Michael O'Neill's keynote is done with both his permission and that of the Shelley Conference 2017. I thank them both. Michael is a Professor of English at Durham University. He was Head of Department from 1997 to 2000 and from 2002 to 2005. From 2005-11, he was a Director (Arts and Humanities) of the Institute of Advanced Study (IAS) at Durham University; he served as the Acting Executive Director of the IAS from January 2011 until May 2012. He is a Founding Fellow of the English Association, on the Editorial Boards of the Keats-Shelley Review, Romantic Circles, Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, Romanticism, The Wordsworth Circle, and CounterText, Chair of the International Byron Society's Advisory Board and Chair of the Wordsworth Conference Foundation. In 2005 he established and is Director of an intra-departmental research group working on Romantic Dialogues and Legacies. He has written many books on Shelley, including The Oxford Handbook of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Literary Life and The Human Mind's Imaginings: Conflict and Achievement in Shelley's Poetry.Read more about him here.

Background on The Shelley Conference

What follows is an edited version of the CFP prepared by conference organizer, Anna Mercer for The Shelley Conference 2017. You can read the original version here.

On 14 and 15 of September 2017 a two-day conference in London, England celebrated the writings of two major authors from the Romantic Period: Percy Bysshe Shelley (PBS) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (MWS).

There is a continuing scholarly fascination with all things 'Shelley' which is due in part to the

unprecedented access we now have to their texts (in annotated scholarly editions) and manuscripts (presented in facsimile and transcript). The Shelleys' works are more readily available than ever before. However somewhat disturbingly, there is no annual or even semi-regular conference dedicated to PBS (comparable to those that exist for other Romantic writers). It was this fact that prompted Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal to organise The Shelley Conference 2017.

Shockingly, it has taken almost 200 years for detailed, comprehensive editions of PBS's works to appear. I believe he is the only major poet in the English literary canon to be so woefully under served. However, two editions are nearing completion: The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook; and The Poems of Shelley edited Kelvin Everest, G.M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan. There is much, therefore, to celebrate. In addition there is the astonishing Shelley-Godwin Archive which will provide, according to the website, "the digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft, bringing together online for the first time ever the widely dispersed handwritten legacy of this uniquely gifted family of writers." It must be seen to be believed.

Conferences at Gregynog in 1978, 1980, and 1992 and the Percy Shelley Bicentennial Conference in New York in 1992 have provided a wonderful legacy for future Shelleyan academics, and it is in the spirit of these events The Shelley Conference 2017 was undertaken. MWS is included in this new conference, as she also does not have her own regular academic event. However, the recent conference 'Beyond Frankenstein's Shadow' (Nancy, France, 2016) focused specifically on MWS, and the emphasis placed on her work at the 'Summer of 1816' conference (Sheffield, 2016) indicated that her role on the main stage of Romanticism is increasingly appreciated.

It is for these reasons that the 'Shelley' of the conference title was left ambiguous. The Shelleys are increasingly seen as a collaborative literary partnership, and modern criticism reinforces the importance of reading their works in parallel. The nuances of this, however, are far from simple, and this statement does not imply there is anything like a sense of either consistent 'unity' or 'conflict' when considering the Shelleys' literary relationship. This is the kind of issue which was explored at The Shelley Conference 2017 by speakers such as the legendary Nora Crook.

Multiple parallel panel sessions allowed the organizers to present a wide range of exciting papers delivered by researchers from the UK, Europe, and beyond, as well as three featured presentations by eminent Shelley scholars: Kelvin Everest, Nora Crook and Michael O'Neill. These are some of the "superstars" of the Shelleyan world.

The Heart's Echo

The Heart's Echo is a keynote address delivered by Professor Kelvin Everest to The Shelley Conference 2017 in London, England. In a literary tour de force, Kelvin Everest draws on a lifetime of Shelley scholarship to discern patterns and consistency in the complex poetic universe of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I found this speech to be profoundly moving; it was like watching a great painter at work on his masterpiece - I was in awe. Professor Everest's love for his subject matter shone through also in moving readings of some of Shelley's most beautiful poetry including The Cloud, When the Lamp is Shattered, Hellas and To Jane, The Recollection. In a letter to me Nora Crook, who Kelvin referred to as our "greatest living Shelley scholar", remarked, that "it was the most intense conference speech I have ever experienced." Now you too can enjoy Professor Everest's brilliant presentation.

The Heart's Echo is a keynote address delivered by Professor Kelvin Everest to The Shelley Conference 2017 in London, England. In a literary tour de force, Kelvin Everest draws on a lifetime of Shelley scholarship to discern patterns and consistency in the complex poetic universe of Percy Bysshe Shelley. I found this speech to be profoundly moving; it was like watching a great painter at work on his masterpiece - I was in awe. Professor Everest's love for his subject matter shone through also in moving readings of some of Shelley's most beautiful poetry including The Cloud, When the Lamp is Shattered, Hellas and To Jane, The Recollection. In a letter to me Nora Crook, who Kelvin referred to as our "greatest living Shelley scholar", remarked, that "it was the most intense conference speech I have ever experienced." Now you too can enjoy Professor Everest's brilliant presentation.

Everest tells us that Shelley's poetical development was an "immensely complex consolidation of what's gone before: the journeys of his mind had been on, overlaying and underpinning each new departure." He then sets himself the task of discerning pattern and consistency in what appears to be the chaotic poetic universe of Percy Bysshe Shelley. He notes, "The onward rush of Shelley's life is characterized by elements that repeat, echoingly." He points to what he calls Shelley's "ubiquitous tendency to return again and again to certain poetic conceptions, images, ideas and specific words which is relatively consistent. This quality knits together all of his output from Queen Mab to The Triumph of Life."

Join Professor Everest as he takes on a poignant journey through the mind of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Background

What follows is an edited version of the CFP prepared by conference organizer, Anna Mercer for The Shelley Conference 2017. You can read the original version here.

On 14 and 15 of September 2017 a two-day conference in London, England celebrated the writings of two major authors from the Romantic Period: Percy Bysshe Shelley (PBS) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (MWS).

There is a continuing scholarly fascination with all things 'Shelley' which is due in part to the

unprecedented access we now have to their texts (in annotated scholarly editions) and manuscripts (presented in facsimile and transcript). The Shelleys' works are more readily available than ever before. However somewhat disturbingly, there is no annual or even semi-regular conference dedicated to PBS (comparable to those that exist for other Romantic writers). It was this fact that prompted Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal to organise The Shelley Conference 2017.

Shockingly, it has taken almost 200 years for detailed, comprehensive editions of PBS's works to appear. I believe he is the only major poet in the English literary canon to be so woefully under served. However, two editions are nearing completion: The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook; and The Poems of Shelley edited Kelvin Everest, G.M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan. There is much, therefore, to celebrate. In addition there is the astonishing Shelley-Godwin Archive which will provide, according to the website, "the digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft, bringing together online for the first time ever the widely dispersed handwritten legacy of this uniquely gifted family of writers." It must be seen to be believed.

Conferences at Gregynog in 1978, 1980, and 1992 and the Percy Shelley Bicentennial Conference in New York in 1992 have provided a wonderful legacy for future Shelleyan academics, and it is in the spirit of these events The Shelley Conference 2017 was undertaken. MWS is included in this new conference, as she also does not have her own regular academic event. However, the recent conference 'Beyond Frankenstein's Shadow' (Nancy, France, 2016) focused specifically on MWS, and the emphasis placed on her work at the 'Summer of 1816' conference (Sheffield, 2016) indicated that her role on the main stage of Romanticism is increasingly appreciated.

It is for these reasons that the 'Shelley' of the conference title was left ambiguous. The Shelleys are increasingly seen as a collaborative literary partnership, and modern criticism reinforces the importance of reading their works in parallel. The nuances of this, however, are far from simple, and this statement does not imply there is anything like a sense of either consistent 'unity' or 'conflict' when considering the Shelleys' literary relationship. This is the kind of issue which was explored at The Shelley Conference 2017 by speakers such as the legendary Nora Crook.

Multiple parallel panel sessions have allowed the organizers to present a wide range of exciting papers delivered by researchers from the UK, Europe, and beyond, as well as three featured presentations by eminent Shelley scholars: Kelvin Everest, Nora Crook and Michael O'Neill. These are some of the "superstars" of the Shelleyan world.

Mary Shelley's Editing of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Today I am pleased to present the first of the plenaries which were featured at The Shelley Conference 2017: Nora Crook's: Mary Shelley's Editing of Percy Bysshe Shelley. This lyrical, intimate and passionate presentation by one of the preeminent authorities on Percy and Mary Shelley provides insights into the extraordinary care with which Mary edited her husband's poetical works. I was spell bound. It is not to be missed. Grab a favourite beverage, pull up a chair and prepare to be beguiled!

What follows is an edited version of the CFP prepared by Anna Mercer for The Shelley Conference 2017. You can read the original version here.

On 14 and 15 of September 2017 a two-day conference in London, England celebrated the writings of two major authors from the Romantic Period: Percy Bysshe Shelley (PBS) and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (MWS).

There is a continuing scholarly fascination with all things 'Shelley' which is due in part to the

unprecedented access we now have to their texts (in annotated scholarly editions) and manuscripts (presented in facsimile and transcript). The Shelleys' works are more readily available than ever before. However somewhat disturbingly, there is no annual or even semi-regular conference dedicated to PBS (comparable to those that exist for other Romantic writers). It was this fact that prompted Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal to organise The Shelley Conference 2017.

Shockingly, it has taken almost 200 years for detailed, comprehensive editions of PBS's works to appear. I believe he is the only major poet in the English literary canon to be so woefully under served. However, two editions are nearing completion: The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley edited by Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook; and The Poems of Shelley edited Kelvin Everest, G.M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan. There is much, therefore, to celebrate. In addition there is the astonishing Shelley-Godwin Archive which will provide, according to the website, "the digitized manuscripts of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft, bringing together online for the first time ever the widely dispersed handwritten legacy of this uniquely gifted family of writers." It must be seen to be believed.

Conferences at Gregynog in 1978, 1980, and 1992 and the Percy Shelley Bicentennial Conference in New York in 1992 have provided a wonderful legacy for future Shelleyan academics, and it is in the spirit of these events The Shelley Conference 2017 was undertaken. MWS is included in this new conference, as she also does not have her own regular academic event. However, the recent conference 'Beyond Frankenstein's Shadow' (Nancy, France, 2016) focused specifically on MWS, and the emphasis placed on her work at the 'Summer of 1816' conference (Sheffield, 2016) indicated that her role on the main stage of Romanticism is increasingly appreciated.

It is for these reasons that the 'Shelley' of the conference title was left ambiguous. The Shelleys are increasingly seen as a collaborative literary partnership, and modern criticism reinforces the importance of reading their works in parallel. The nuances of this, however, are far from simple, and this statement does not imply there is anything like a sense of either consistent 'unity' or 'conflict' when considering the Shelleys' literary relationship. This is the kind of issue which was explored at The Shelley Conference 2017 by speakers such as the legendary Nora Crook.

Prof. Nora Crook speaking at The Shelley Conference 2017

Multiple parallel panel sessions have allowed the organizers to present a wide range of exciting papers delivered by researchers from the UK, Europe, and beyond, as well as three featured presentations by eminent Shelley scholars: Kelvin Everest, Nora Crook and Michael O'Neill. These are some of the "superstars" of the Shelleyan world.

Today I am pleased to present the first of the three featured presentations: Nora Crook speaking on Mary Shelley's Editing of Percy Bysshe Shelley. This lyrical and passionate presentation provides insights into the extraordinary care with which Mary edited and even enhanced her husband's poetic works. 21st Century scholarship is increasingly focused on the literary collaboration of these two uniquely gifted creators. The picture that is emerging is wondrous, and nothing at all like the two dimensional, comic book perversion offered by Haifaa al-Mansour's movie "Mary Shelley". See my review here.

Next week? Professor Kelvin Everest on "The Heart's Echo"; a touching, beautifully judged paean to the way in which certain themes echoed down the corridors of Percy Shelley's short life.

Nora Crook is Emeritus Professor at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. Her chief

publications include the co-authored Shelley's Venomed Melody (Cambridge University

Press 1986), a monograph on Shelley and medicine, which was followed by Kipling's

Myths of Love and Death (Macmillan, 1990) and numerous journal articles and chapters.

Her international reputation was established by her textual work on the Shelleys

between 1991-2002. Editions of two of P.B. Shelley's notebooks in the Bodleian Library

alternated with her general editorship of twelve volumes of Mary Shelley's works, which

included her own editions of Frankenstein and Valperga. Currently she is co-general

editor of the multi-volume Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Johns Hopkins, 2000

onward), with special responsibility for poems edited by Mary Shelley after PB Shelley's death.

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte

- Adonais

- Alastor

- Anna Mercer

- Anna Valle

- Byron

- Carl McKeating

- Chamonix

- Ciaran O'Rourke

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Trelawney

- Engels

- Frankenstein

- G. John Samuel

- Gabriel Charton

- Gandhi

- Heidi Thompson

- Hellas

- Hymn Before Sunrise

- James Bieri

- James Connolly

- Jitendra Mishra

- Joseph Severn

- Keats Foundation

- Kelvin Everest

- Larry Henderson

- Manfred

- Mary Shelley

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Mont Blanc

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- On Christianity

- On Life

- Pandemic

- Paul Foot

- PMS Dawson

- Prometheus Unbound

- Protestant Cemetery

- Queen Mab

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Roland Duerksen

- Rome

- Shelley Conference 2017

- Sir william Drummond

- Skepticism

- Stuart Curran

- Subramania Bharati

- The Cenci

- The Cloud

- The Shelley Conference 2017

- The Sublime

- To Jane With a Guitar

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Ulisse Lendaro

- Ursula K Le Guin

- Victorian Literature

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- William Bell Scott