Shelley’s Verse

PB Shelley, “To S and C” (1819-20)

In 1820, Shelley began toying with the idea of publishing (as he put it) “a little volume of popular songs wholly political & destined to awaken & direct the imagination of the reformers.” As with other poems to be included in this collection, “To S. and C.” confronts some of the major events of the day with a bouncy, catchy rhythm, and it offers instruction through a collection of straightforward but powerful similes. Such a style of writing seems to affirm the view that England’s common people, and not just educated elites, have a part to play in the country’s reform movements.

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840)

As from their ancestral oak

Two empty ravens wind their clarion,

Yell by yell, and croak for croak;

When they scent the noonday smoke

Of fresh human carrion:—

As two gibbering night-birds flit

From their homes of deadly yew

Through the night to frighten it—

When the moon is in a fit,

And the stars are none or few:—

As a shark and dogfish wait

Under an Atlantic isle

For the Negroship whose freight

Is the theme of their debate,

Wrinkling their red gills the while:—

Are ye—two vultures sick for battle,

Two scorpions under one wet stone,

Two bloodless wolves whose dry throats rattle,

Two crows perched on the murrained cattle,

Two vipers tangled into one.

In 1820, Shelley began toying with the idea of publishing (as he put it) “a little volume of popular songs wholly political & destined to awaken & direct the imagination of the reformers.” As with other poems to be included in this collection, “To S. and C.” confronts some of the major events of the day with a bouncy, catchy rhythm, and it offers instruction through a collection of straightforward but powerful similes. Such a style of writing seems to affirm the view that England’s common people, and not just educated elites, have a part to play in the country’s reform movements.

Lord Sidmouth and Viscount Castlereagh, two prominent political figures and recurrent targets in Shelley’s poetry, are depicted in Shelley’s poem as birds of prey, safely concealed in “their ancestral oak” (read: England), or as the sharks following slave ships across the Atlantic. The implications of these powerful similes would be clear enough to readers of Shelley’s day: England’s countrymen and women were not merely subjects to a pair of unpredictable, warmongering tyrants; they were also their principle victims.

Commentary by Jon Kerr.

P.B. Shelley, “Ode to Liberty” (1820)

Jean-Pierre Houël, Prise de la Bastille (1789)

“Come thou [Liberty], but lead out of the inmost cave

Of man's deep spirit, as the morning-star

Beckons the Sun from the Eoan wave,

Wisdom. I hear the pennons of her car

Self-moving, like cloud charioted by flame;

Comes she not, and come ye not,

Rulers of eternal thought,

To judge, with solemn truth, life's ill-apportioned lot?

Blind Love, and equal Justice, and the Fame

Of what has been, the Hope of what will be?

O Liberty! if such could be thy name

Wert thou disjoined from these, or they from thee:

If thine or theirs were treasures to be bought

By blood or tears, have not the wise and free

Wept tears, and blood like tears?” (Lines 256-270)

Written in 1820, Shelley’s poem celebrates Liberty, a personified force that, after centuries of slumber, seems to be on the verge of reawakening at long last. While 1819 was a terrible year for reformers across Europe, 1820 brought new optimism: revolutions in Spain, Portugal, and Italy prompts Shelley to imagine the spread of Liberty further, across the world and into countries still under the yoke of tyranny. For Shelley, however, Liberty is not only a matter of representative government, fair pay, and impartial legal systems; it is also a state of mind. Beginning with a cave metaphor that might make us think of Plato’s famous allegory, Shelley imagines Liberty, leading the human spirit out of the shadows and into the light of wisdom, love, and hope—the qualities linked to human perseverance in the quest toward happiness.

But is the spread of freedom inevitable, according to Shelley’s poem? Think of how often Shelley gives us his picture of Liberty—what it is, when it appears—through questions: “Comes she not…?” While anticipated by Shelley, Liberty’s triumph is far from certain. After all, in the view of history presented in the poem, Liberty appears at several epochs—in classical Greece, the Roman Republic, and Saxon England—only to disappear once more. Written at a moment of tremendous upheaval in European history, Shelley’s poem captures the optimism that he and his fellow reformers experienced, but he never shies away from the vulnerability of it all. As his poem explores the struggle for freedom throughout history, it seems to be telling us that if the triumph of Liberty is not simply inevitable, the ongoing struggle to achieve and defend it becomes all the more important.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Men of England”

In Europe’s revolutionary era, the contest over hearts and minds was fought across many cultural arenas. We get a sense of this in “Men of England,” a poem written in the style of the popular songs that, in the England of Shelley’s day, would have been the stuff of riotous sing-alongs in pubs, fairs, and other centres of public life.

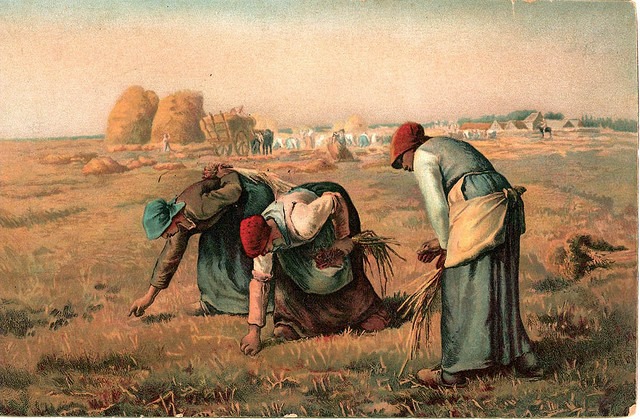

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gleaners (1857)

INTRODUCTION

Welcome the The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. This site is managed by me, Graham Henderson. My blog feature reflections on the philosophy, politics and poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, a radical thinker who has receded into the shadows. Shelley has the power to enthrall, thrill and inspire. His poetry changed the world and can do so again.

When Shelley famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist," he deliberately, intentionally and provocatively nailed his colours to the mast knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus, the titan who rebelled against the gods of Olympus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered "philanthropy" to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley identified closely with his own poetic creation, Prometheus. In using the term, Shelley is telling us he is a humanist - a radical concept in his priest-ridden times.

When he wrote these words he was declaring war against the hegemonic power structure of his time. Shelley was in effect saying: I am against god. I am against the king. I am the modern Prometheus. And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people. Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

As Paul Foot so ably summed it up in his wonderful book, "Red Shelley":

"Shelley was not dull. His poems reverberate with energy and excitement. He decked the grand ideas which inspired him in language which enriches them and sharpen communication with the people who can put them into effect."

It is time to bring him back – we need him; tyrannies, be they of the mind or the world, are phoenix-like and continually threaten to undermine our liberties. Shelley's ideas constitute a tool kit of sorts which have direct applicability to our own times. As did Shelley, we too live in a time when tyrants, theocrats and demagogues are surging into the mainstream.

Please enjoy this website! There are guest contributors, book reviews and much much more.

Men of England

“Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save

From the cradle to the grave

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear? …

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells—

In hall ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom

Trace your grave and build your tomb

And weave your winding-sheet—till fair

England be your Sepulchre.”

In Europe’s revolutionary era, the contest over hearts and minds was fought across many cultural arenas. We get a sense of this in “Men of England,” a poem written in the style of the popular songs that, in the England of Shelley’s day, would have been the stuff of riotous sing-alongs in pubs, fairs, and other centres of public life. In 1820, writing politically-charged content intended for a mass audience was extremely dangerous: reformers who wrote for common people often found themselves facing libel or even treason charges. On the other hand, finding innovative ways to reach out to common, illiterate people was deemed crucial if England was to achieve grassroots change.

Shelley commits himself to just this kind of project in “Men of England.” Shelley writes in easy-to-understand language and adopts a bouncy metrical structure (“tetrameter,” or lines of eight syllables) that makes memorization easy. The metaphors Shelley utilizes for describing the situation in England are simple but powerful: worker bees—the hard-working men of England—toil for the benefit of the “drones,” the non-labouring members of the hive. Capping it all off are a number of rhetorical questions that bring readers or listeners directly into the poem’s action: why “plough for the lords who lay ye low?”

Like the people of London described by William Blake, Shelley’s workers are adorned with “mind-forg’d manacles,” since they wear the very chains they themselves have “wrought.” While they remain complicit in their subjugation, understanding this fact is the first precondition for achieving lasting change. And it couldn’t come at a more crucial time: Shelley writes that by toiling the earth for other people’s profit, the labourers are in fact digging their own mass grave, one Shelley calls “England.”

Commentary by Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, “A New National Anthem” (1819 or 1820)

Nanine Vallain, Liberty (1793)

"God prosper, speed, and save,

God raise from England’s grave

Her murdered Queen!

Pave with swift victory

The steps of Liberty,

Whom Britons own to be

Immortal Queen…

[Bewilder] her enemies

In their own dark disguise,--

God save our Queen!

All earthly things that dare

Her sacred name to bear,

Strip them, as kings are, bare;

God save the Queen!

Be her eternal throne

Built in our hearts alone--

God save the Queen!

Let the oppressor hold

Canopied seats of gold;

She sits enthroned of old

O’er our hearts, Queen!”

Written in 1819 or early 1820, Shelley’s alternative national anthem marks a continuation of the strategies Shelley adopts in works like “Men of England: A Song” and “The Mask of Anarchy”: to write poetry in a “vernacular” style, adopting popular genres like the song to reach the kinds of lower-class readers who might not ordinarily read poetry. Far less dense and challenging than much of his other poetry, Shelley’s anthem is written in a shorter, bouncy metre and evokes the same patriotic emotions that most anthems stoke. But make no mistake: Shelley’s poem is no ordinary celebration of King and country!

The “monarch” celebrated here is not King George III, but “Liberty,” a personified presence that Shelley calls the only true ruler of Britain. Evoking the regicides recently experienced in England and France, Shelley claims that this “Queen” has lately been murdered at the hands of traitorous politicians attempting to curb the reform movement in Britain. But Liberty also lives in the hearts of freedom-loving Britons, which means that she cannot be stopped by shows of force. Thus, while Shelley reflects upon a recent turn for the worse in Britain’s state of political affairs, his poem also offers some consolation: if Liberty lives in the hearts and minds of British people, its reign is inevitable, at least in the long run.

P.B. Shelley, “Sonnet: Political Greatness” (1820 or 1821)

Antonio Joli, View of ... Benevento (1759)

“Nor happiness, nor majesty, nor fame,

Nor peace, nor strength, nor skill in arms or arts,

Shepherd those herds whom tyranny makes tame;

Verse echoes not one beating of their hearts,

History is but the shadow of their shame,

Art veils her glass, or from the pageant starts

As to oblivion their blind millions fleet,

Staining that Heaven with obscene imagery

Of their own likeness. What are numbers knit

By force or custom? Man who man would be,

Must rule the empire of himself; in it

Must be supreme, establishing his throne

On vanquished will, quelling the anarchy

Of hopes and fears, being himself alone.”

Shelley apparently wrote “Political Greatness” with Benevento in mind, an Italian city that briefly established itself as a republic between July 1820 and the spring of 1821. Whether Shelley wrote his poem before or after the fall of the republican city is an interesting conundrum, given the poem’s questioning attitude about the possibilities of political revolution. Do the people of Benevento embody Shelley’s portrait of successful revolutionaries, who must exercise self-awareness and mastery of their own will before they are able to create political change? Or does Benevento illustrate the failure that awaits spontaneous and disorganized mass uprisings?

Whatever the answer to this question, this sonnet certainly captures Shelley at a moment of political uncertainty. While 1820 was a fairly good year for progressives, witnessing successful reform movements in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Brazil, Shelley dedicates his poem to asking hard questions about the possibilities for achieving political change. Shelley doesn’t renounce the hope of revolution or reform; rather, he suggests that an inner revolution—a self-disciplining, whereby we are able to master our desires and better know ourselves—must take place before we are able to achieve widespread social change. Shelley seems to have understood a crucial lesson imparted by reformers from Socrates to William Godwin to Martin Luther King Jr.: that in a world in which power is deeply ingrained not only in social institutions but in the collective psyche, the effort to change minds is perhaps more important than the effort to change laws.

P.B. Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" (1819)

J.M.W. Turner, Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps (1812)

“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse within its grave, until

Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o'er the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver; hear, oh hear!”

The opening stanza of Shelley’s poem “Ode to the West Wind” moves like a gust, pushing the reader through a rich assortment of images. We begin with the Wind itself, ushering in the Fall—the time of impending death in the natural world, where leaves fall from trees, black, red, and yellow, like the plague-stricken. The Wind puts to rest the forest’s seeds as well, although we learn that this death is only temporary: like the trumpets of the apocalypse described in Revelations, the wind, now returned in the Spring, blasts its “clarion” to usher in a second life. This is no Christian vision, however. As is so common in Shelley’s poetry, “Ode to the West Wind” introduces Christian symbolism only to subvert it: the supreme power to give and take life, to “destroy” and “preserve,” belongs solely to Nature and not to God.

What else is going on in Shelley’s effort to make sense of the cyclical movement of the seasons and the elusive power of the Wind? We’d love to hear your thoughts on this Shelley classic!

Percy Shelley, “Love’s Philosophy”

A cheeky seduction poem, “Love’s Philosophy” gives us a speaker who attempts to use his arts to capture the heart (and perhaps more) of a love interest: “look around at the world,” he says to his unnamed lover. “Everywhere, you see things coming together, unifying in matter and spirit. Isn’t it a crime against our nature not to do the same?”

However, the poem doesn’t just showcase Shelley’s playful side. It demonstrates the immense influence that all things natural had on many writers of this time.

John Kerr’s Tuesday Verse

Shelley’s Love’s Philosophy

J.M.W. Turner, "The Bay of Baiae with Apollo and the Sibyl" (1823)

“The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the ocean,

The winds of heaven mix for ever

With a sweet emotion;

Nothing in the world is single;

All things by a law divine

In one spirit meet and mingle.

Why not I with thine?—

See the mountains kiss high heaven

And the waves clasp one another;

No sister-flower would be forgiven

If it disdained its brother;

And the sunlight clasps the earth

And the moonbeams kiss the sea:

What is all this sweet work worth

If thou kiss not me?”

A cheeky seduction poem, “Love’s Philosophy” (1819) gives us a speaker who attempts to use his wiles to capture the heart of a love interest: “look around at the world,” he says to his unnamed, hoped-for lover. “Everywhere, you see things coming together, unifying in matter and spirit. Isn’t it a crime against our nature not to do the same?”

However, the poem doesn’t just showcase Shelley’s playful side (as well as his gift for lyricism). It demonstrates the immense influence that all things natural had on many writers of this time. Nature wasn’t embraced by Romantic writers merely because it looked pretty and allowed people to forget the grind of their daily lives; rather, the natural world was often seen as a system that contained important lessons for how human beings lived their lives. When Shelley looks at nature in this poem, he sees cooperation and reconciliation between living things (like flowers), objects (mountains and skies) and elemental forces (sunlight). Living naturally, the poem concludes, means seeing ourselves as a part of this system and applying its lessons to how we live with others. This is what Shelley means by “love’s philosophy.”

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toronto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doctoral fellowship.

PB Shelley, Preface to Frankenstein

The Preface to Frankenstein—written by Percy, oddly enough—brings us back to the now legendary moment of inspiration that gave us Mary Shelley’s famous novel: vacationing at Lake Geneva with a circle of friends and fellow writers, the Shelleys are confined indoors due to inclement weather. Reading German horror stories by candlelight, the crew eventually settles on a competition proposed by Lord Byron. The competition is simple: who can write the best horror story? In the months and years ahead, Byron and Percy—the two literary heavyweights of the party—lose interest and take up other projects; Mary, meanwhile, sets to work on what will become Frankenstein, one of the most celebrated English novels of all time.

Still from James Whale's Frankenstein (1931)

“The event on which this fiction is founded has been supposed, by Dr. Darwin, and some of the physiological writers of Germany, as not of impossible occurrence. I shall not be supposed as according the remotest degree of serious faith to such an imagination; yet, in assuming it as the basis of a work of fancy, I have not considered myself as merely weaving a series of supernatural terrors. … [H]owever impossible as a physical fact, [Frankenstein] affords a point of view to the imagination for the delineating of human passions more comprehensive and commanding than any which the ordinary relations of existing events can yield…

… Other motives were mingled with [this one] as the work proceeded. I am by no means indifferent to the manner in which whatever moral tendencies exist in the sentiments or characters it contains shall affect the reader; yet my chief concern in this respect has been limited to… the exhibition of the amiableness of domestic affection, and the excellence of universal virtue. The opinions which naturally spring from the character and situation of the hero are by no means to be conceived as existing always in my own conviction; nor is any inference justly to be drawn from the following pages as prejudicing any philosophical doctrine of whatever kind.

It is a subject also of additional interest to the author that this story was begun in the majestic region where the scene is principally laid, and in society which cannot cease to be regretted. I passed the summer of 1816 in the environs of Geneva. The season was cold and rainy, and in the evenings we crowded around a blazing wood fire, and occasionally amused ourselves with some German stories of ghosts, which happened to fall into our hands. These tales excited in us a playful desire of imitation. Two other friends (a tale from the pen of one of whom would be far more acceptable to the public than anything I can ever hope to produce) and myself agreed to write each a story founded on some supernatural occurrence.

The weather, however, suddenly became serene; and my two friends left me on a journey among the Alps, and lost, in the magnificent scenes which they present, all memory of their ghostly visions. The following tale is the only one which has been completed.”

Jon Kerr Comments:

The Villa Diodati.

The Preface to Frankenstein—written by Percy, oddly enough—brings us back to the now legendary moment of inspiration that gave us Mary Shelley’s famous novel: vacationing at Lake Geneva with a circle of friends and fellow writers, the Shelleys are confined indoors due to inclement weather. Reading German horror stories by candlelight, the crew eventually settles on a competition proposed by Lord Byron. The competition is simple: who can write the best horror story? In the months and years ahead, Byron and Percy—the two literary heavyweights of the party—lose interest and take up other projects; Mary, meanwhile, sets to work on what will become Frankenstein, one of the most celebrated English novels of all time.

Percy’s Preface gives us much more than biographical fun-facts, however. It also shines interesting light on the kinds of theories, world events, and reading materials that preoccupied Mary (and Percy) as Frankenstein gradually came into being. The “Dr. Darwin” alluded to in the opening paragraph is not Charles but rather his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, a scientist in his own right who believed that with enough know-how, scientists could soon learn how to galvanize human corpses. According to Percy, Mary’s novel draws on theories put forward by the scientists of her day, which qualifies Frankenstein as one of the first science fiction novels.

The Preface also reveals a little bit about how Percy read his wife’s novel. As Percy sees it, the strength of Mary’s novel lay in its powerful depiction of family relationships and its optimistic rendering of human virtues. Apparently, Percy read Frankenstein as many contemporary readers still do: as expressing Rousseau’s idea that people are born inherently good, only to be made wicked by a corrupt society. It seems clear from this kind of critical engagement that Percy understood the exceptional power of Frankenstein, and regarded Mary as an author with a truly “comprehensive and commanding” understanding of the human condition.

I, for one, am left with some questions on reading the Preface. For example, Percy seems to regard Victor, rather than the creature, as the hero of the novel. What heroic qualities do you think Shelley could have envisioned in a character that most readers now see as the novel’s villain? Give us your thoughts in the comments section!

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toronto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doctoral fellowship.

P.B. Shelley, “To the Lord Chancellor”

As American’s go to the polls today in a series of epochal mid-term elections, Shelley’s To the Lord Chancellor seems a more than appropriate choice for our Tuesday Verse selection. As Timothy Webb once noted, politics was perhaps the consuming passion of Shelley’s life. On the 6 November 1819, right around the time he might have been writing this poem, Shelley wrote to his friends the Gisbornes saying, “I have deserted the odorous gardens of literature to journey across the great sandy desert of Politics; not, you may imagine, without the hope of finding some enchanted paradise.” Shelley was what was known as a perfectibilist, someone who believed in the perfectibility of humans. He even developed a sophisticated political and social theory to compliment this belief. This does NOT mean Shelley was a utopian - he emphatically was not. But he did believe in the gradual evolution of the human species toward something like perfection.

As American’s go to the polls today in a series of epochal mid-term elections, Shelley’s To the Lord Chancellor (written in 1819 or 20) seems a more than appropriate choice for our Tuesday Verse selection. As Timothy Webb once noted, politics was perhaps the consuming passion of Shelley’s life. On the 6 November 1819, right around the time he might have been writing this poem, Shelley wrote to his friends the Gisbornes saying, “I have deserted the odorous gardens of literature to journey across the great sandy desert of Politics; not, you may imagine, without the hope of finding some enchanted paradise.” Shelley was what was known as a perfectibilist, someone who believed in the perfectibility of humans. He even developed a sophisticated political and social theory to compliment this belief. This does NOT mean Shelley was a utopian - he emphatically was not. But he did believe in the gradual evolution of the human species toward something like perfection.

How sad he would be to see our world in the condition it is in - a world in which tyranny is on the rise, not on the wane. A world in which wealth is concentrated in ever fewer hands. A world in which we still have kings and in which religious superstitions govern the behaviour of so many. Despairingly, he might conclude, that things to not appear to be getting more “perfect”.

Perhaps today the people of America will strike a blow against racism, intolerance and bigotry. Perhaps today we can take a step toward a better future. Perhaps today we can aspire to be better.

John Scott (1751–1838), afterwards 1st Earl of Eldon, Lord Chancellor of England by William Owen

“Thy country's curse is on thee! Justice sold,

Truth trampled, Nature’s landmarks overthrown,

And heaps of fraud-accumulated gold,

Plead, loud as thunder, at Destruction's throne.

And whilst that sure slow Angel which aye stands

Watching the beck of Mutability

Delays to execute her high commands,

And, though a nation weeps, spares thine and thee,

Oh, let a father's curse be on thy soul,

And let a daughter's hope be on thy tomb;

Be both, on thy gray head, a leaden cowl

To weigh thee down to thine approaching doom.

I curse thee by a parent's outraged love,

By hopes long cherished and too lately lost,

By gentle feelings thou couldst never prove,

By griefs which thy stern nature never crossed […]

Yes, the despair which bids a father groan,

And cry, 'My children are no longer mine--

The blood within those veins may be mine own,

But--Tyrant--their polluted souls are thine;—

I curse thee--though I hate thee not.-- O slave!

If thou couldst quench the earth-consuming Hell

Of which thou art a daemon, on thy grave

This curse should be a blessing. Fare thee well!”

Jon Kerr Comments:

John Scott (1751-1838), the Earl of Eldon and the Lord Chancellor from 1801-1827, was a major figure in Britain’s conservative establishment for most of Shelley’s adult life. From his position in Britain’s courts of law, the Chancellor had a hand in suppressing the work of radical publishers and writers or revoking the copyright of “seditious” writings—forms of character assassination that significantly impacted the careers of some of the era’s leading reformers. The Chancellor also affected Shelley’s life in a far more personal fashion, however. In 1817, Scott denied Shelley custody of his children on the grounds that the father’s political principles would lead to an “immoral and vicious” upbringing for his children.

“To the Lord Chancellor” affirms the maxim that the personal is the political. In this way, the poem is unique in Shelley’s corpus for its attempt to expose systemic political wrongs from the vantage point of a suffering father. While Shelley begins by outlining the Chancellor’s complicity in British tyranny—“Justice sold, | Truth trampled…”—the poem’s real source of power lies in its focus on the individual rather than the system, on the pain of everyday people that get caught in the wheels of British “law and order.” This also leads Shelley to reflect darkly on the country’s future, since the system Shelley exposes impacts not only parents but children, whose experience in such ordeals leave them scarred, or as Shelley writes, “polluted.”

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toronto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doctoral fellowship.

“Time” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

In his life and writings, Shelley was fascinated with the element—water—that would one day take his life. In the above poem, Shelley explores another subject, “time,” by linking it to the great waterways of the world.

J.M.W. Turner, Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842)

Time

“Unfathomable Sea! whose waves are years,

Ocean of Time, whose waters of deep woe

Are brackish with the salt of human tears!

Thou shoreless flood, which in thy ebb and flow

Claspest the limits of mortality!

And sick of prey, yet howling on for more,

Vomitest thy wrecks on its inhospitable shore;

Treacherous in calm, and terrible in storm,

Who shall put forth on thee,

Unfathomable Sea?”

John Kerr comments:

In his life and writings, Shelley was fascinated with the element—water—that would one day take his life. In the above poem, Shelley explores another subject, “time,” by linking it to the great waterways of the world. Like time, the “unfathomable sea” wields great power over human life, and its unknowability makes it sublime—that is, both captivating and terrifying.

The ocean, whose space appears to stretch on infinitely, would seem to be the best symbol we have for thinking about time. But for Shelley, the ocean also says something about human limitations. Readers of the second-generation Romantics might recognize this convention: as the primary setting of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, for instance, the sea illustrates the confusion and turmoil—you might say adriftness—both of the Byronic hero and the British society he comes from. There is also Keats’ famous epitaph, “here lies one whose name was writ in water,” which shares with Shelley’s poem a fear that our lives might be as transient and unremembered as a wave breaking on the shore. For these writers, the great waterways are both majestic illustrations of the world’s hidden power, and ever-present reminders of our vulnerability as mortal beings.

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toronto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doctoral fellowship.

P.B. Shelley, "Ozymandias" (1817)

The product of a friendly writing competition between Shelley and his friend Horace Smith, the sonnet “Ozymandias” presents us with a striking image: a hulking, shattered, and half-buried statue of Ozymandias, better known as Ramses II, the famed Egyptian pharaoh

Unknown Sculptor, Younger Memnon (c. 1270 BCE)

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert... near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Jon Kerr's comment:

The product of a friendly writing competition between Shelley and his friend Horace Smith, the sonnet “Ozymandias” presents us with a striking image: a hulking, shattered, and half-buried statue of Ozymandias, better known as Ramses II, the famed Egyptian pharaoh. The once mighty king speaks to us through the monument’s inscription: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings.” Surely with “Ozymandias,” Shelley had in mind the great kings of his own historical moment who arrogantly believed, like Ozymandias, that their power was absolute, perhaps even divinely inspired. According to Ozymandias, his power should make even the mightiest of human beings feel small, but in Shelley’s poem, it is the power of time, and not of kings, which prevails. But what kind of power is this? Is time an improving force, bringing down arrogant tyrants like Ramses? Or does time simply destroy everything, both good and bad? It’s worth thinking about the fact that the “Ozymandias” of the poem is not only a king, but a work of art, a beautiful piece of sculpture. Shelley is concerned here with the glorious fall of bad rulers, but is he also using this poem to reflect on his anxiety that time “buries” the artists (like himself) along with the tyrants?

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toironto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doc fellowship.

William Blake, "The Tyger" (1794)

Blake’s “Tyger” is a classic of British Romantic poetry, one we couldn’t resist branching out to explore for this week’s Tuesday Verse. Blake’s poem marvels at the tiger, a sublime creature for its ability to excite both awe and terror. However, Blake is equally attracted to the shadowy figure who, hunched over his anvil, forges into being this majestic apex predator, as if from steel and fire. What kind of prime creator, Blake wonders, could have brought to life such a creature, perfect in its killing ability?

An engraving, made by Blake himself, from an early edition of The Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794).

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Blake’s “The Tyger” is a classic of British Romantic poetry, one we couldn’t resist branching out to explore for this week’s Tuesday Verse. The famous poem considers the tiger, an animal native to South and South-East Asia but which Blake may have seen at the travelling circuses that showcased the earth’s wonders to London’s paying customers. Blake’s poem marvels at the tiger, a sublime creature for its ability to excite both awe and terror. However, Blake is equally attracted to the shadowy figure who, hunched over his anvil, forges into being this majestic apex predator, as if from steel and fire.

What kind of prime creator, Blake wonders, could have brought to life such a creature, perfect in its killing ability? Could such a figure have also created the lamb, the counterpart to the tiger in Blake’s myth whose life suggests both purity and the dangers awaiting it in a world of terrors? Blake’s poem doesn’t answer these questions on its own; rather, like many poems in The Songs of Innocence and of Experience, its interest is in framing competing ways of understanding the world and exploring the oppositions (tiger and lamb, experience and innocence) at the heart of human experience.

This is our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary Comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, "Sonnet: Ye Hasten to the Grave"

In England, the sonnet has often been used to explore themes of transience, death, and immortality. Shelley's "Ye Hasten to the Grave" continues this trend; however, it does so by refocusing attention away from contemplation about death and the afterlife and back toward the pleasures of life in the here-and-now. Shelley partly frames his sonnet as a series of rhetorical questions for the kind of person who seeks to embrace death as part of his or her religious convictions. For such a person, of course, death is not the end of life but rather life's transformation into something new and blissful. In keeping with his atheism, Shelley implies that the belief in such an afterlife is a form of misdirected hope stemming from hubris or conventional thinking (what Shelley calls "the world's livery"). But perhaps worst of all, in seeking out "a refuge in the cavern of grey death," such a person flees not only life's pain but also its pleasure, the "green and pleasant path" that suggests a power and beauty in life's here-and-now.

Even so, it's worth considering that Shelley's poem doesn't actually affirm very much. Even though his position is atheistical, Shelley has given us a poem more interested in asking questions (about life, death, and belief) rather than averring a new doctrine.

John William Waterhouse, Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May (1909)

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind, which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go,

And all that never yet was known would know—

O whither hasten ye, that thus ye press

With such swift feet life’s green and pleasant path,

Seeking, alike from happiness and woe,

A refuge in the cavern of grey death?

O heart, and mind, and thoughts! what thing do you

Hope to inherit in the grave below?

In England, the sonnet has often been used to explore themes of transience, death, and immortality. Shelley's "Ye Hasten to the Grave" continues this trend; however, it does so by refocusing attention away from contemplation about death and the afterlife and back toward the pleasures of life in the here-and-now. Shelley partly frames his sonnet as a series of rhetorical questions for the kind of person who seeks to embrace death as part of his or her religious convictions. For such a person, of course, death is not the end of life but rather life's transformation into something new and blissful. In keeping with his atheism, Shelley implies that the belief in such an afterlife is a form of misdirected hope stemming from hubris or conventional thinking (what Shelley calls "the world's livery"). But perhaps worst of all, in seeking out "a refuge in the cavern of grey death," such a person flees not only life's pain but also its pleasure, the "green and pleasant path" that suggests a power and beauty in life's here-and-now.

Even so, it's worth considering that Shelley's poem doesn't actually affirm very much. Even though his position is atheistical, Shelley has given us a poem more interested in asking questions (about life, death, and belief) rather than averring a new doctrine.

This is our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, "An Exhortation" (1820)

In "An Exhortation," Shelley addresses a question that preoccupied his age: what is a poet? In attempting to answer this question, Shelley uses as his primary metaphor the chameleon, the shape-shifting, colour-adjusting reptile. Readers of the Romantics might know that, funny enough, the chameleon was also central to Keats' understanding of the poet. According to Keats, the poet's distinguishing trait was their ability to write convincingly of any life situation, event, or mindset, an (adapt)ability that stemmed from their deep knowledge of human nature.

Chameleons feed on light and air:

Poets’ food is love and fame:

If in this wide world of care

Poets could but find the same

With as little toil as they,

Would they ever change their hue

As the light chameleons do,

Suiting it to every ray

Twenty times a day?

Poets are on this cold earth,

As chameleons might be,

Hidden from their early birth

In a cave beneath the sea;

Where light is, chameleons change:

Where love is not, poets do:

Fame is love disguised: if few

Find either, never think it strange

That poets range.

Yet dare not stain with wealth or power

A poet’s free and heavenly mind:

If bright chameleons should devour

Any food but beams and wind,

They would grow as earthly soon

As their brother lizards are.

Children of a sunnier star,

Spirits from beyond the moon,

Oh, refuse the boon!

In "An Exhortation," Shelley addresses a question that preoccupied his age: what is a poet? In attempting to answer this question, Shelley uses as his primary metaphor the chameleon, the shape-shifting, colour-adjusting reptile. Readers of the Romantics might know that, funny enough, the chameleon was also central to Keats' understanding of the poet. According to Keats, the poet's distinguishing trait was their ability to write convincingly of any life situation, event, or mindset, an (adapt)ability that stemmed from their deep knowledge of human nature.

The chameleon poet of Shelley's strange little poem is a bit different from Keats's, however. Playing with one of his favourite ancient texts, Plato's Symposium, Shelley claims that the poet shape-shifts their way through life in pursuit of their unattainable goals: love and fame. (Elsewhere in Tuesday Verse, we've explored how, in Shelley's writing, "love" is often depicted as a fraternal power, a bond with humankind at large). The poet will never achieve the love they pursue. However, this can be a good thing for Shelley, since the acquisition of this kind of love can bring "wealth and power"--the things that degrade all of us, but especially the poet. If the poet is destined to wander their way through life in pursuit of ideals that cannot be attained, this process also gives to poetry is most important qualities: creative freedom, integrity preserved from the world's corrupting influences, and truth.

This is our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

Caption: photo of a chameleon.

P.B. Shelley, from "Julian and Maddalo" (1818-19)

“Julian and Maddalo” is a conversation poem that centres on the relationship between two figures: the aristocratic Maddalo (who resembles Shelley’s friend and fellow poet Lord Byron) and Julian (an idealist who closely resembles Shelley himself). Throughout the poem, the conversations and experiences of the two compatriots touch on subjects that preoccupied both Shelley and Byron in their life and writing. Julian argues for the mind’s power to change itself and the world around it. The far more skeptical Maddalo calls this “Utopian.” The will is not free, says Maddalo; rather, our lives are shaped by forces beyond our control.

Lord Byron and Shelley remained close friends influenced each other's writing, despite their notable and differences in outlook.

“‘See

This lovely child, blithe, innocent and free;

She spends a happy time with little care,

While we to such sick thoughts subjected are

As came on you last night. It is our will

That thus enchains us to permitted ill.

We might be otherwise. We might be all

We dream of happy, high, majestical.

Where is the love, beauty, and truth we seek

But in our mind? and if we were not weak

Should we be less in deed than in desire?’

‘Ay, if we were not weak—and we aspire

How vainly to be strong!’ said Maddalo:

‘You talk Utopia.’ ‘It remains to know,’

I then rejoin'd, ‘and those who try may find

How strong the chains are which our spirit bind;

Brittle perchance as straw…’”

“Julian and Maddalo” is a conversation poem that centres on the relationship between two figures: the aristocratic Maddalo (who resembles Shelley’s friend and fellow poet Lord Byron) and Julian (an idealist who closely resembles Shelley himself). Throughout the poem, the conversations and experiences of the two compatriots touch on subjects that preoccupied both Shelley and Byron in their life and writing. Julian (whose voice begins our excerpt) argues for the mind’s power to change itself and the world around it: “look at your child,” he encourages Maddalo; “there is nothing preventing us from achieving this state of innocent happiness except our own self-imposed agony. Like William Blake, Julian proposes that the chains we wear in our lives are “mind forg’d.” But we “might be otherwise,” he says; “We might be all | we dream of.”

The far more skeptical Maddalo calls this “Utopian”—Julian is being naively idealistic, in other words. Maddalo takes Julian’s rhetorical question—“if we were not weak | Should we be less in deed than in desire?”—and turns it on its head: the problem, he says, is that we are weak, and only “aspire… vainly to be strong.” The will is not free, says Maddalo; rather, our lives are shaped by forces beyond our control.

As is common in debates staged between the two companions throughout the poem, the argument here ends in a stalemate: Julian gets the closing word, but merely says “it remains for us to find out | How strong the chains are which our spirit bind.” In other words, even if Shelley closely resembles Julian in certain ways, his objective in this poem isn’t to demonstrate the superiority of his worldview over that of Byron’s. Neither side is proven correct or incorrect in the poem; rather, Shelley seems far more interested in faithfully exploring competing ways of seeing the world. In fact, Shelley might even be using some of Byron’s ideas to test out the durability of his own convictions: can I be absolutely certain that “we might be all | We dream of”? How do I know? Shelley seems to be asking himself. As we’ve explored elsewhere on Tuesday Verse, this willingness to ask hard questions about his own values and worldview is a recurrent characteristic of Shelley’s scepticism.

This is our "Tuesday Verse" series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

Captions: Thomas Phillips, Lord Byron (1813); Alfred Clint, Percy Shelley (1829)

P.B. Shelley, “The Flower that Smiles Today” (1821-22)

Likely written in the final year or so of his life, “The Flower that Smiles Today” captures Shelley’s increasing preoccupation with the transience of life and its joys. The final years of Shelley’s life were marked by increasing difficulties, both personal and political: between 1816 and 1819, Shelley and Mary had lost three children, which brought growing strain to their marriage; at the early 1820s came with a series of critical setbacks to England’s reform movement that, just a few years prior, seemed on the verge of creating real change in the country. These issues hang over Shelley’s mutability poems like this one, which ponders how it is possible to survive particular joys—friendship, love, beauty—once we know we can never experience them again.

Some of you might also notice connections, both stylistic and thematic, with some of Byron’s poetry, which often ponders similar questions. Both the Byronic hero and the speaker of Shelley’s poem capture the zeitgeist of Britain’s revolutionary period as it gradually drew to a close: that is, both reflect upon the disappointed hopes that come to people (and societies) that once seemed destined to achieve great things.

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Funeral of Shelley (1889)

INTRODUCTION

Welcome the The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. This site is managed by me, Graham Henderson. My blog feature reflections on the philosophy, politics and poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, a radical thinker who has receded into the shadows. Shelley has the power to enthrall, thrill and inspire. His poetry changed the world and can do so again.

When Shelley famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist," he deliberately, intentionally and provocatively nailed his colours to the mast knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus, the titan who rebelled against the gods of Olympus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered "philanthropy" to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley identified closely with his own poetic creation, Prometheus. In using the term, Shelley is telling us he is a humanist - a radical concept in his priest-ridden times.

When he wrote these words he was declaring war against the hegemonic power structure of his time. Shelley was in effect saying: I am against god. I am against the king. I am the modern Prometheus. And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people. Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

As Paul Foot so ably summed it up in his wonderful book, "Red Shelley":

"Shelley was not dull. His poems reverberate with energy and excitement. He decked the grand ideas which inspired him in language which enriches them and sharpen communication with the people who can put them into effect."

It is time to bring him back – we need him; tyrannies, be they of the mind or the world, are phoenix-like and continually threaten to undermine our liberties. Shelley's ideas constitute a tool kit of sorts which have direct applicability to our own times. As did Shelley, we too live in a time when tyrants, theocrats and demagogues are surging into the mainstream.

Please enjoy this website! There are guest contributors, book reviews and much much more.

Please tell me where you discovered this post by writing to me at graham@grahamhenderson.ca

The Flower that Smiles Today

The flower that smiles to-day

To-morrow dies;

All that we wish to stay

Tempts and then flies.

What is this world's delight?

Lightning that mocks the night,

Brief even as bright.

Virtue, how frail it is!

Friendship how rare!

Love, how it sells poor bliss

For proud despair!

But we, though soon they fall,

Survive their joy, and all

Which ours we call.

Whilst skies are blue and bright,

Whilst flowers are gay,

Whilst eyes that change ere night

Make glad the day;

Whilst yet the calm hours creep,

Dream thou—and from thy sleep

Then wake to weep.

Likely written in the final year or so of his life, “The Flower that Smiles Today” captures Shelley’s increasing preoccupation with the transience of life and its joys. The final years of Shelley’s life were marked by increasing difficulties, both personal and political: between 1816 and 1819, Shelley and Mary had lost three children, which brought growing strain to their marriage; at the early 1820s came with a series of critical setbacks to England’s reform movement that, just a few years prior, seemed on the verge of creating real change in the country. These issues hang over Shelley’s mutability poems like this one, which ponders how it is possible to survive particular joys—friendship, love, beauty—once we know we can never experience them again.

Some of you might also notice connections, both stylistic and thematic, with some of Byron’s poetry, which often ponders similar questions. Both the Byronic hero and the speaker of Shelley’s poem capture the zeitgeist of Britain’s revolutionary period as it gradually drew to a close: that is, both reflect upon the disappointed hopes that come to people (and societies) that once seemed destined to achieve great things.

Commentary Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, “Lines Written During the Castlereagh Administration” (1819-20)

Unknown Painter, “Lord Castlereagh, Marquess of Londonderry” (1809-10)

“Corpses are cold in the tomb;

Stones on the pavement are dumb;

Abortions are dead in the womb,

And their mothers look pale—like the death- white shore

Of Albion, free no more.

Her sons are as stones in the way--

They are masses of senseless clay--

They are trodden, and move not away,--

The abortion with which SHE travaileth

Is Liberty, smitten to death.

Then trample and dance, thou Oppressor!

For thy victim is no redresser;

Thou art sole lord and possessor

Of her corpses, and clods, and abortions—they pave

Thy path to the grave.

Hearest thou the festival din

Of Death, and Destruction, and Sin,

And Wealth crying 'Havoc!' within?

’Tis the bacchanal triumph that makes Truth dumb,

Thine Epithalamium.

Ay, marry thy ghastly wife!

Let Fear and Disquiet and Strife

Spread thy couch in the chamber of Life!

Marry Ruin, thou Tyrant! and Hell be thy guide

To the bed of the bride!”

Viscount Castlereagh, the British Secretary of State from 1812-22, casts a dark shadow in Shelley’s poetry. This is because Castlereagh lead some of the most pivotal—and controversial—foreign policy moves of Shelley’s era: in addition to breaking Irish independence movements and bringing the Celtic island under the dominion of the United Kingdom, Castlereagh spearheaded the work of restoration in the years following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. Royal families reassumed positions of power, and with them came a new era in Europe, one committed to crushing the reform movements spurred by the French Revolution two decades earlier.

Shelley’s poem invokes a gristly image that captures this dispiriting moment in European history. Shelley describes “Albion” (that is, “England”) as a failed pregnancy, a symbol that evokes how optimism about a better life ahead can so swiftly transition toward despair about the future. England, a country formerly looked on as Europe’s most progressive country, now lies broken, her son, “Liberty,” dead in the womb.

It’s worth comparing Shelley’s picture of England to William Blake’s “London” (1794), another poem that uses a “blasted” child and ailing mother to reflect on England’s uncertain future. Shelley was likely unfamiliar with Blake’s poem, but the similarities between their poetry is worth noting. Both poems reflect a fear experienced by many in this period: that decades of dearly-bought progress was on the brink of being dissolved by the kinds of backroom dealing that “makes Truth dumb” and spreads “Fear, Discomfort, and Strife.”

P.B. Shelley, “Mask of Anarchy” (1819)

“The Mask of Anarchy” begins on an unassuming note: Shelley’s claim that his “visions of Poesy” have come to him in a dream might lead the reader to imagine that what follows is a flight into imaginative wonder and away from reality. But as with “Queen Mab,” Shelley’s dream vision does not take us away from the world but forces us to confront its ugliest features. Alluding to the four horsemen of the apocalypse described in the Book of Revelations, the opening of “The Mask of Anarchy” presents four figures who, according to Shelley, were undertaking their own world-destroying fury: Murder, Fraud, Hypocrisy, and Anarchy. Unlike in Revelations, however, these are not abstract forces in a spiritual conflict between good and evil. Shelley gives his evil corporeal form and well-recognized names: Viscount Castlereagh; Lord Eldon; Lord Sidmouth; and the royalty, churchmen, and timeservers of Britain’s establishment class. If the apocalypse is coming, in other words, it will be achieved through Britain’s unholy trinity of “God, and King, and Law.”

In 1819, it might very well have felt like the apocalypse was coming: food shortages, economic turmoil, and widespread civil unrest plagued the realm. But Shelley’s poem also registers some hope. If poets are prophetic figures whose deep knowledge of their times creates knowledge and permits change (ideas explored in the essay “Defense of Poetry”), then Shelley’s dream vision might produce “the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time”—a different, brighter future, in other words.

Unknown Illustrator, illustration of the Peterloo Massacre (1819)

I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

I met Murder on the way -

He had a mask like Castlereagh -

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him…

Next cam Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

His big tears, for he wept well,

Turned to mill-stones as they fell…

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,

Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy

On a crocodile rode by.

And many more Destructions played

In this ghastly masquerade,

All disguised, even to the eyes,

Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw -

'I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!"

“The Mask of Anarchy” begins on an unassuming note: Shelley’s claim that his “visions of Poesy” have come to him in a dream might lead the reader to imagine that what follows is a flight into imaginative wonder and away from reality. But as with “Queen Mab,” Shelley’s dream vision does not take us away from the world but forces us to confront its ugliest features. Alluding to the four horsemen of the apocalypse described in the Book of Revelations, the opening of “The Mask of Anarchy” presents four figures who, according to Shelley, were undertaking their own world-destroying fury: Murder, Fraud, Hypocrisy, and Anarchy. Unlike in Revelations, however, these are not abstract forces in a spiritual conflict between good and evil. Shelley gives his evil corporeal form and well-recognized names: Viscount Castlereagh; Lord Eldon; Lord Sidmouth; and the royalty, churchmen, and timeservers of Britain’s establishment class. If the apocalypse is coming, in other words, it will be achieved through Britain’s unholy trinity of “God, and King, and Law.”

In 1819, it might very well have felt like the apocalypse was coming: food shortages, economic turmoil, and widespread civil unrest plagued the realm. But Shelley’s poem also registers some hope. If poets are prophetic figures whose deep knowledge of their times creates knowledge and permits change (ideas explored in the essay “Defense of Poetry”), then Shelley’s dream vision might produce “the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time”—a different, brighter future, in other words.

P.B. Shelley, from “A Defense of Poetry” (1821)

Alfred Clint, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1829)

“Poets… are not only the authors of language and of music, of the dance, and architecture, and statuary, and painting: they are the institutors of laws, and the founders of civil society, and the inventors of the arts of life, and the teachers… Poets, according to the circumstances of the age and nation in which they appeared, were called, in the earlier epochs of the world, legislators, or prophets: a poet essentially comprises and unites both these characters. For he not only beholds intensely the present as it is, and discovers those laws according to which present things ought to be ordered, but he beholds the future in the present, and his thoughts are the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time.”

In his great essay “A Defense of Poetry,” Shelley gives us his famous definition of the poet: to be a poet is to represent a spirit of change, both within the world of letters and beyond it. Those who write verse are poets, of course, but poets also create in other ways: musicians, performers, sculptors, and painters all embody the force of poetry—that is to say, a kind of creativity that challenges and thereby inspires change.

Shelley returns to an ancient understanding of the poet as a prophet, one who, like the writer of Job or The Odyssey, was gifted with a rich and mysterious language from the gods. But Shelley’s prophet-poet is not literally given a glimpse into the future from on high, as a Biblical prophet would be. Rather, with his ear to the ground, the poet possesses a deep understanding of the world, and this gives him or her a sense of where their society is going. This, finally, is what makes the poet an ideal “legislator”: the poet’s deep knowledge both of human nature and the social conditions of his/her time means that their best gifts come in the form of social instruction and leadership.

Shelley wrote at a time in which the value of what we now call “the arts” was questioned like never before. Up went the cries: what is the value of reading or writing something like poetry? Shouldn’t a young man like Shelley commit himself to something more socially beneficial and less self-indulgent? Shelley responds by claiming that in order for a society to function at its best, it requires the kind of creative voices that allows it to know itself, to be self-critical, and to change.

P.B. Shelley, “One Word is Too Often Profaned” (1821)

George Clint, Jane Williams (c. 1822).

"One word is too often profaned

For me to profane it,

One feeling too falsely disdained

For thee to disdain it;

One hope is too like despair

For prudence to smother,

And pity from thee more dear

Than that from another.

I can give not what men call love,

But wilt thou accept not

The worship the heart lifts above

And the Heavens reject not,—

The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow?"

“One Word” was written for Jane Williams, a family friend with whom Shelley had become infatuated toward the end of his life. (Fun fact: Shelley’s boating companion on that ill-fated trip across the Gulf of Spezia was Edward Williams, Jane’s husband. He also drowned when their boat foundered in a storm.) The poem captures both the intensity and necessary secrecy of Shelley’s love: “love” is the “one word” Shelley refuses to use in the opening stanza both because it is often used too freely (and thus degraded) and because it might be dangerous: what if Jane “disdains” his avowal of love? What if there is something “profane” about how Shelley loves? We sense the claustrophobia of the poem, as Shelley struggles to give language to his feelings for a woman with whom he, Mary, and her husband Edward shared a home during the final period of his life.

The compromise, voiced in the poem’s second stanza, is platonic: “wilt thou accept,” Shelley asks Jane, “The worship the heart lifts above | And the Heavens reject not”? Jane becomes something like a muse, as Shelley voices his love in spiritual terms: it is now a form of devotion toward “something afar | From the sphere of our sorrow.”

This is part of our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

Welcome to the archives to our Tuesday Verse. Feel free to have a wander through our pages, which provide brief commentary on Shelley's life, times, and writing. Have a recommendation for a Shelley work you'd like us to tackle?Don’t hesitate to reach out!

- John Kerr

- Ode to the West Wind

- Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

- Ode to Liberty

- Blake

- Labour

- perfectibilism

- Liberty

- Freedom

- A New National Anthem

- Lord Sidmouth

- Syncretic

- Pantheism

- Frankenstein

- Lord Eldon

- mutability

- Men of England: A Song

- To S and C

- Byron

- romantic philosophy

- Sonnet: Political Greatness

- Globalization

- Love's Philosophy

- JMW Turner

- The Mask of Anarchy

- Lord Castlereagh

- Julian and Maddalo

- Human rights

- Percy Shelley

- Keats

- Proletariat

- The Flower that Smiles Today

- Mary Shelley

- Democracy

- Politics

- Ramses II

- Ozymandias