Shelley’s Verse

P.B. Shelley, “Ode to Liberty” (1820)

Jean-Pierre Houël, Prise de la Bastille (1789)

“Come thou [Liberty], but lead out of the inmost cave

Of man's deep spirit, as the morning-star

Beckons the Sun from the Eoan wave,

Wisdom. I hear the pennons of her car

Self-moving, like cloud charioted by flame;

Comes she not, and come ye not,

Rulers of eternal thought,

To judge, with solemn truth, life's ill-apportioned lot?

Blind Love, and equal Justice, and the Fame

Of what has been, the Hope of what will be?

O Liberty! if such could be thy name

Wert thou disjoined from these, or they from thee:

If thine or theirs were treasures to be bought

By blood or tears, have not the wise and free

Wept tears, and blood like tears?” (Lines 256-270)

Written in 1820, Shelley’s poem celebrates Liberty, a personified force that, after centuries of slumber, seems to be on the verge of reawakening at long last. While 1819 was a terrible year for reformers across Europe, 1820 brought new optimism: revolutions in Spain, Portugal, and Italy prompts Shelley to imagine the spread of Liberty further, across the world and into countries still under the yoke of tyranny. For Shelley, however, Liberty is not only a matter of representative government, fair pay, and impartial legal systems; it is also a state of mind. Beginning with a cave metaphor that might make us think of Plato’s famous allegory, Shelley imagines Liberty, leading the human spirit out of the shadows and into the light of wisdom, love, and hope—the qualities linked to human perseverance in the quest toward happiness.

But is the spread of freedom inevitable, according to Shelley’s poem? Think of how often Shelley gives us his picture of Liberty—what it is, when it appears—through questions: “Comes she not…?” While anticipated by Shelley, Liberty’s triumph is far from certain. After all, in the view of history presented in the poem, Liberty appears at several epochs—in classical Greece, the Roman Republic, and Saxon England—only to disappear once more. Written at a moment of tremendous upheaval in European history, Shelley’s poem captures the optimism that he and his fellow reformers experienced, but he never shies away from the vulnerability of it all. As his poem explores the struggle for freedom throughout history, it seems to be telling us that if the triumph of Liberty is not simply inevitable, the ongoing struggle to achieve and defend it becomes all the more important.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Men of England”

In Europe’s revolutionary era, the contest over hearts and minds was fought across many cultural arenas. We get a sense of this in “Men of England,” a poem written in the style of the popular songs that, in the England of Shelley’s day, would have been the stuff of riotous sing-alongs in pubs, fairs, and other centres of public life.

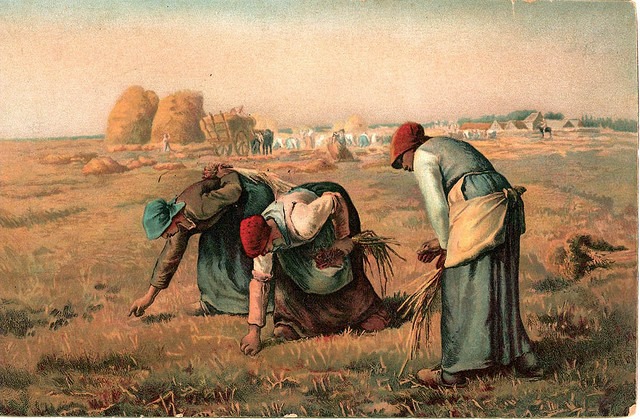

Jean-Francois Millet, The Gleaners (1857)

INTRODUCTION

Welcome the The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. This site is managed by me, Graham Henderson. My blog feature reflections on the philosophy, politics and poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, a radical thinker who has receded into the shadows. Shelley has the power to enthrall, thrill and inspire. His poetry changed the world and can do so again.

When Shelley famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist," he deliberately, intentionally and provocatively nailed his colours to the mast knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus, the titan who rebelled against the gods of Olympus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered "philanthropy" to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley identified closely with his own poetic creation, Prometheus. In using the term, Shelley is telling us he is a humanist - a radical concept in his priest-ridden times.

When he wrote these words he was declaring war against the hegemonic power structure of his time. Shelley was in effect saying: I am against god. I am against the king. I am the modern Prometheus. And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people. Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

As Paul Foot so ably summed it up in his wonderful book, "Red Shelley":

"Shelley was not dull. His poems reverberate with energy and excitement. He decked the grand ideas which inspired him in language which enriches them and sharpen communication with the people who can put them into effect."

It is time to bring him back – we need him; tyrannies, be they of the mind or the world, are phoenix-like and continually threaten to undermine our liberties. Shelley's ideas constitute a tool kit of sorts which have direct applicability to our own times. As did Shelley, we too live in a time when tyrants, theocrats and demagogues are surging into the mainstream.

Please enjoy this website! There are guest contributors, book reviews and much much more.

Men of England

“Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save

From the cradle to the grave

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear? …

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells—

In hall ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom

Trace your grave and build your tomb

And weave your winding-sheet—till fair

England be your Sepulchre.”

In Europe’s revolutionary era, the contest over hearts and minds was fought across many cultural arenas. We get a sense of this in “Men of England,” a poem written in the style of the popular songs that, in the England of Shelley’s day, would have been the stuff of riotous sing-alongs in pubs, fairs, and other centres of public life. In 1820, writing politically-charged content intended for a mass audience was extremely dangerous: reformers who wrote for common people often found themselves facing libel or even treason charges. On the other hand, finding innovative ways to reach out to common, illiterate people was deemed crucial if England was to achieve grassroots change.

Shelley commits himself to just this kind of project in “Men of England.” Shelley writes in easy-to-understand language and adopts a bouncy metrical structure (“tetrameter,” or lines of eight syllables) that makes memorization easy. The metaphors Shelley utilizes for describing the situation in England are simple but powerful: worker bees—the hard-working men of England—toil for the benefit of the “drones,” the non-labouring members of the hive. Capping it all off are a number of rhetorical questions that bring readers or listeners directly into the poem’s action: why “plough for the lords who lay ye low?”

Like the people of London described by William Blake, Shelley’s workers are adorned with “mind-forg’d manacles,” since they wear the very chains they themselves have “wrought.” While they remain complicit in their subjugation, understanding this fact is the first precondition for achieving lasting change. And it couldn’t come at a more crucial time: Shelley writes that by toiling the earth for other people’s profit, the labourers are in fact digging their own mass grave, one Shelley calls “England.”

Commentary by Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, “A New National Anthem” (1819 or 1820)

Nanine Vallain, Liberty (1793)

"God prosper, speed, and save,

God raise from England’s grave

Her murdered Queen!

Pave with swift victory

The steps of Liberty,

Whom Britons own to be

Immortal Queen…

[Bewilder] her enemies

In their own dark disguise,--

God save our Queen!

All earthly things that dare

Her sacred name to bear,

Strip them, as kings are, bare;

God save the Queen!

Be her eternal throne

Built in our hearts alone--

God save the Queen!

Let the oppressor hold

Canopied seats of gold;

She sits enthroned of old

O’er our hearts, Queen!”

Written in 1819 or early 1820, Shelley’s alternative national anthem marks a continuation of the strategies Shelley adopts in works like “Men of England: A Song” and “The Mask of Anarchy”: to write poetry in a “vernacular” style, adopting popular genres like the song to reach the kinds of lower-class readers who might not ordinarily read poetry. Far less dense and challenging than much of his other poetry, Shelley’s anthem is written in a shorter, bouncy metre and evokes the same patriotic emotions that most anthems stoke. But make no mistake: Shelley’s poem is no ordinary celebration of King and country!

The “monarch” celebrated here is not King George III, but “Liberty,” a personified presence that Shelley calls the only true ruler of Britain. Evoking the regicides recently experienced in England and France, Shelley claims that this “Queen” has lately been murdered at the hands of traitorous politicians attempting to curb the reform movement in Britain. But Liberty also lives in the hearts of freedom-loving Britons, which means that she cannot be stopped by shows of force. Thus, while Shelley reflects upon a recent turn for the worse in Britain’s state of political affairs, his poem also offers some consolation: if Liberty lives in the hearts and minds of British people, its reign is inevitable, at least in the long run.

P.B. Shelley, “Sonnet: Political Greatness” (1820 or 1821)

Antonio Joli, View of ... Benevento (1759)

“Nor happiness, nor majesty, nor fame,

Nor peace, nor strength, nor skill in arms or arts,

Shepherd those herds whom tyranny makes tame;

Verse echoes not one beating of their hearts,

History is but the shadow of their shame,

Art veils her glass, or from the pageant starts

As to oblivion their blind millions fleet,

Staining that Heaven with obscene imagery

Of their own likeness. What are numbers knit

By force or custom? Man who man would be,

Must rule the empire of himself; in it

Must be supreme, establishing his throne

On vanquished will, quelling the anarchy

Of hopes and fears, being himself alone.”

Shelley apparently wrote “Political Greatness” with Benevento in mind, an Italian city that briefly established itself as a republic between July 1820 and the spring of 1821. Whether Shelley wrote his poem before or after the fall of the republican city is an interesting conundrum, given the poem’s questioning attitude about the possibilities of political revolution. Do the people of Benevento embody Shelley’s portrait of successful revolutionaries, who must exercise self-awareness and mastery of their own will before they are able to create political change? Or does Benevento illustrate the failure that awaits spontaneous and disorganized mass uprisings?

Whatever the answer to this question, this sonnet certainly captures Shelley at a moment of political uncertainty. While 1820 was a fairly good year for progressives, witnessing successful reform movements in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Brazil, Shelley dedicates his poem to asking hard questions about the possibilities for achieving political change. Shelley doesn’t renounce the hope of revolution or reform; rather, he suggests that an inner revolution—a self-disciplining, whereby we are able to master our desires and better know ourselves—must take place before we are able to achieve widespread social change. Shelley seems to have understood a crucial lesson imparted by reformers from Socrates to William Godwin to Martin Luther King Jr.: that in a world in which power is deeply ingrained not only in social institutions but in the collective psyche, the effort to change minds is perhaps more important than the effort to change laws.

P.B. Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" (1819)

J.M.W. Turner, Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps (1812)

“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse within its grave, until

Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o'er the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver; hear, oh hear!”

The opening stanza of Shelley’s poem “Ode to the West Wind” moves like a gust, pushing the reader through a rich assortment of images. We begin with the Wind itself, ushering in the Fall—the time of impending death in the natural world, where leaves fall from trees, black, red, and yellow, like the plague-stricken. The Wind puts to rest the forest’s seeds as well, although we learn that this death is only temporary: like the trumpets of the apocalypse described in Revelations, the wind, now returned in the Spring, blasts its “clarion” to usher in a second life. This is no Christian vision, however. As is so common in Shelley’s poetry, “Ode to the West Wind” introduces Christian symbolism only to subvert it: the supreme power to give and take life, to “destroy” and “preserve,” belongs solely to Nature and not to God.

What else is going on in Shelley’s effort to make sense of the cyclical movement of the seasons and the elusive power of the Wind? We’d love to hear your thoughts on this Shelley classic!

P.B. Shelley, "Ozymandias" (1817)

The product of a friendly writing competition between Shelley and his friend Horace Smith, the sonnet “Ozymandias” presents us with a striking image: a hulking, shattered, and half-buried statue of Ozymandias, better known as Ramses II, the famed Egyptian pharaoh

Unknown Sculptor, Younger Memnon (c. 1270 BCE)

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert... near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Jon Kerr's comment:

The product of a friendly writing competition between Shelley and his friend Horace Smith, the sonnet “Ozymandias” presents us with a striking image: a hulking, shattered, and half-buried statue of Ozymandias, better known as Ramses II, the famed Egyptian pharaoh. The once mighty king speaks to us through the monument’s inscription: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings.” Surely with “Ozymandias,” Shelley had in mind the great kings of his own historical moment who arrogantly believed, like Ozymandias, that their power was absolute, perhaps even divinely inspired. According to Ozymandias, his power should make even the mightiest of human beings feel small, but in Shelley’s poem, it is the power of time, and not of kings, which prevails. But what kind of power is this? Is time an improving force, bringing down arrogant tyrants like Ramses? Or does time simply destroy everything, both good and bad? It’s worth thinking about the fact that the “Ozymandias” of the poem is not only a king, but a work of art, a beautiful piece of sculpture. Shelley is concerned here with the glorious fall of bad rulers, but is he also using this poem to reflect on his anxiety that time “buries” the artists (like himself) along with the tyrants?

Jon Kerr is a recently graduated from the University of Toironto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doc fellowship.

P.B. Shelley, "Sonnet: Ye Hasten to the Grave"

In England, the sonnet has often been used to explore themes of transience, death, and immortality. Shelley's "Ye Hasten to the Grave" continues this trend; however, it does so by refocusing attention away from contemplation about death and the afterlife and back toward the pleasures of life in the here-and-now. Shelley partly frames his sonnet as a series of rhetorical questions for the kind of person who seeks to embrace death as part of his or her religious convictions. For such a person, of course, death is not the end of life but rather life's transformation into something new and blissful. In keeping with his atheism, Shelley implies that the belief in such an afterlife is a form of misdirected hope stemming from hubris or conventional thinking (what Shelley calls "the world's livery"). But perhaps worst of all, in seeking out "a refuge in the cavern of grey death," such a person flees not only life's pain but also its pleasure, the "green and pleasant path" that suggests a power and beauty in life's here-and-now.

Even so, it's worth considering that Shelley's poem doesn't actually affirm very much. Even though his position is atheistical, Shelley has given us a poem more interested in asking questions (about life, death, and belief) rather than averring a new doctrine.

John William Waterhouse, Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May (1909)

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind, which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go,

And all that never yet was known would know—

O whither hasten ye, that thus ye press

With such swift feet life’s green and pleasant path,

Seeking, alike from happiness and woe,

A refuge in the cavern of grey death?

O heart, and mind, and thoughts! what thing do you

Hope to inherit in the grave below?

In England, the sonnet has often been used to explore themes of transience, death, and immortality. Shelley's "Ye Hasten to the Grave" continues this trend; however, it does so by refocusing attention away from contemplation about death and the afterlife and back toward the pleasures of life in the here-and-now. Shelley partly frames his sonnet as a series of rhetorical questions for the kind of person who seeks to embrace death as part of his or her religious convictions. For such a person, of course, death is not the end of life but rather life's transformation into something new and blissful. In keeping with his atheism, Shelley implies that the belief in such an afterlife is a form of misdirected hope stemming from hubris or conventional thinking (what Shelley calls "the world's livery"). But perhaps worst of all, in seeking out "a refuge in the cavern of grey death," such a person flees not only life's pain but also its pleasure, the "green and pleasant path" that suggests a power and beauty in life's here-and-now.

Even so, it's worth considering that Shelley's poem doesn't actually affirm very much. Even though his position is atheistical, Shelley has given us a poem more interested in asking questions (about life, death, and belief) rather than averring a new doctrine.

This is our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

P.B. Shelley, "An Exhortation" (1820)

In "An Exhortation," Shelley addresses a question that preoccupied his age: what is a poet? In attempting to answer this question, Shelley uses as his primary metaphor the chameleon, the shape-shifting, colour-adjusting reptile. Readers of the Romantics might know that, funny enough, the chameleon was also central to Keats' understanding of the poet. According to Keats, the poet's distinguishing trait was their ability to write convincingly of any life situation, event, or mindset, an (adapt)ability that stemmed from their deep knowledge of human nature.

Chameleons feed on light and air:

Poets’ food is love and fame:

If in this wide world of care

Poets could but find the same

With as little toil as they,

Would they ever change their hue

As the light chameleons do,

Suiting it to every ray

Twenty times a day?

Poets are on this cold earth,

As chameleons might be,

Hidden from their early birth

In a cave beneath the sea;

Where light is, chameleons change:

Where love is not, poets do:

Fame is love disguised: if few

Find either, never think it strange

That poets range.

Yet dare not stain with wealth or power

A poet’s free and heavenly mind:

If bright chameleons should devour

Any food but beams and wind,

They would grow as earthly soon

As their brother lizards are.

Children of a sunnier star,

Spirits from beyond the moon,

Oh, refuse the boon!

In "An Exhortation," Shelley addresses a question that preoccupied his age: what is a poet? In attempting to answer this question, Shelley uses as his primary metaphor the chameleon, the shape-shifting, colour-adjusting reptile. Readers of the Romantics might know that, funny enough, the chameleon was also central to Keats' understanding of the poet. According to Keats, the poet's distinguishing trait was their ability to write convincingly of any life situation, event, or mindset, an (adapt)ability that stemmed from their deep knowledge of human nature.

The chameleon poet of Shelley's strange little poem is a bit different from Keats's, however. Playing with one of his favourite ancient texts, Plato's Symposium, Shelley claims that the poet shape-shifts their way through life in pursuit of their unattainable goals: love and fame. (Elsewhere in Tuesday Verse, we've explored how, in Shelley's writing, "love" is often depicted as a fraternal power, a bond with humankind at large). The poet will never achieve the love they pursue. However, this can be a good thing for Shelley, since the acquisition of this kind of love can bring "wealth and power"--the things that degrade all of us, but especially the poet. If the poet is destined to wander their way through life in pursuit of ideals that cannot be attained, this process also gives to poetry is most important qualities: creative freedom, integrity preserved from the world's corrupting influences, and truth.

This is our Tuesday Verse series. Commentary comes from Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English at the University of Toronto with specialization in the Romantics.

Caption: photo of a chameleon.

P.B. Shelley, “The Flower that Smiles Today” (1821-22)

Likely written in the final year or so of his life, “The Flower that Smiles Today” captures Shelley’s increasing preoccupation with the transience of life and its joys. The final years of Shelley’s life were marked by increasing difficulties, both personal and political: between 1816 and 1819, Shelley and Mary had lost three children, which brought growing strain to their marriage; at the early 1820s came with a series of critical setbacks to England’s reform movement that, just a few years prior, seemed on the verge of creating real change in the country. These issues hang over Shelley’s mutability poems like this one, which ponders how it is possible to survive particular joys—friendship, love, beauty—once we know we can never experience them again.

Some of you might also notice connections, both stylistic and thematic, with some of Byron’s poetry, which often ponders similar questions. Both the Byronic hero and the speaker of Shelley’s poem capture the zeitgeist of Britain’s revolutionary period as it gradually drew to a close: that is, both reflect upon the disappointed hopes that come to people (and societies) that once seemed destined to achieve great things.

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Funeral of Shelley (1889)

INTRODUCTION

Welcome the The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley. This site is managed by me, Graham Henderson. My blog feature reflections on the philosophy, politics and poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, a radical thinker who has receded into the shadows. Shelley has the power to enthrall, thrill and inspire. His poetry changed the world and can do so again.

When Shelley famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist," he deliberately, intentionally and provocatively nailed his colours to the mast knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus, the titan who rebelled against the gods of Olympus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered "philanthropy" to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley identified closely with his own poetic creation, Prometheus. In using the term, Shelley is telling us he is a humanist - a radical concept in his priest-ridden times.

When he wrote these words he was declaring war against the hegemonic power structure of his time. Shelley was in effect saying: I am against god. I am against the king. I am the modern Prometheus. And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people. Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

As Paul Foot so ably summed it up in his wonderful book, "Red Shelley":

"Shelley was not dull. His poems reverberate with energy and excitement. He decked the grand ideas which inspired him in language which enriches them and sharpen communication with the people who can put them into effect."

It is time to bring him back – we need him; tyrannies, be they of the mind or the world, are phoenix-like and continually threaten to undermine our liberties. Shelley's ideas constitute a tool kit of sorts which have direct applicability to our own times. As did Shelley, we too live in a time when tyrants, theocrats and demagogues are surging into the mainstream.

Please enjoy this website! There are guest contributors, book reviews and much much more.

Please tell me where you discovered this post by writing to me at graham@grahamhenderson.ca

The Flower that Smiles Today

The flower that smiles to-day

To-morrow dies;

All that we wish to stay

Tempts and then flies.

What is this world's delight?

Lightning that mocks the night,

Brief even as bright.

Virtue, how frail it is!

Friendship how rare!

Love, how it sells poor bliss

For proud despair!

But we, though soon they fall,

Survive their joy, and all

Which ours we call.

Whilst skies are blue and bright,

Whilst flowers are gay,

Whilst eyes that change ere night

Make glad the day;

Whilst yet the calm hours creep,

Dream thou—and from thy sleep

Then wake to weep.

Likely written in the final year or so of his life, “The Flower that Smiles Today” captures Shelley’s increasing preoccupation with the transience of life and its joys. The final years of Shelley’s life were marked by increasing difficulties, both personal and political: between 1816 and 1819, Shelley and Mary had lost three children, which brought growing strain to their marriage; at the early 1820s came with a series of critical setbacks to England’s reform movement that, just a few years prior, seemed on the verge of creating real change in the country. These issues hang over Shelley’s mutability poems like this one, which ponders how it is possible to survive particular joys—friendship, love, beauty—once we know we can never experience them again.

Some of you might also notice connections, both stylistic and thematic, with some of Byron’s poetry, which often ponders similar questions. Both the Byronic hero and the speaker of Shelley’s poem capture the zeitgeist of Britain’s revolutionary period as it gradually drew to a close: that is, both reflect upon the disappointed hopes that come to people (and societies) that once seemed destined to achieve great things.

Commentary Jonathan Kerr, who has recently completed his PhD in English with specialization in the Romantics.

Welcome to the archives to our Tuesday Verse. Feel free to have a wander through our pages, which provide brief commentary on Shelley's life, times, and writing. Have a recommendation for a Shelley work you'd like us to tackle?Don’t hesitate to reach out!

- John Kerr

- Ode to the West Wind

- Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

- Ode to Liberty

- Blake

- Labour

- perfectibilism

- Liberty

- Freedom

- A New National Anthem

- Lord Sidmouth

- Syncretic

- Pantheism

- Frankenstein

- Lord Eldon

- mutability

- Men of England: A Song

- To S and C

- Byron

- romantic philosophy

- Sonnet: Political Greatness

- Globalization

- Love's Philosophy

- JMW Turner

- The Mask of Anarchy

- Lord Castlereagh

- Julian and Maddalo

- Human rights

- Percy Shelley

- Keats

- Proletariat

- The Flower that Smiles Today

- Mary Shelley

- Democracy

- Politics

- Ramses II

- Ozymandias