Sir Humphrey Davy and the Romantics - an Online Course

Professor Sharon Ruston of Lancaster University is offering a free online course through Future Learn called "Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp". These types of course are fun and informative. If you are interested in Shelley you will want to learn more about Davy because Shelley studied him closely. Shelley was one of the last great polymaths - he was well versed with a range of subjects that dwarfs most of his famous contemporaries. Science was one of them. To understand Shelley fully, you need to understand his interest in science - this course can help you to do this.

I am pleased to introduce Sharon Ruston to my readers. Sharon is a Shelley and Romantics scholar who is the Chair of the English Department at Lancaster University. Her main research interests are in the relations between the literature, science and medicine of the Romantic period, 1780-1820. Her first book, Shelley and Vitality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), explored the medical and scientific contexts which inform Shelley's concept of vitality in his major poetry. Her most recent book, Creating Romanticism: Case Studies in the Literature, Science, and Medicine of the 1790s (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) has chapters on Mary Wollstonecraft's interest in natural history, William Godwin's interest in mesmerism, and Humphry Davy’s writings on the sublime. Sharon is currently co-editing the Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy and his Circle, to be published in four volumes by Oxford University Press.

Sharon Ruston, Chair, Department of English, Lancaster University.

Sharon is offering a free online course through Future Learn called "Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp". These types of course are fun and informative. If you are interested in Shelley you will want to learn more about Davy because Shelley studied him closely. Shelley was one of the last great polymaths - he was well versed with a range of subjects that dwarfs most of his famous contemporaries. Science was one of them. To understand Shelley fully, you need to understand his interest in science - this course can help you to do this.

You can find Sharon on Twitter @SharonRuston and at Lancaster University. Here is her guest column.

This autumn you can participate in a free, online course on a man of science whom P. B. Shelley greatly admired, Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829).

Sir Humphry Davy. Thomas Phillips National Portrait Gallery, London

Anyone can sign up and all are welcome from people who know nothing about Davy to those who are already aware of just how fascinating a figure he is. Shelley was certainly interested in Davy: Shelley made copious, extensive notes on one of Davy’s most popular works Elements of Agricultural Chemistry (1813) sometime around 1820. I have speculated on why Shelley was so interested in these in my book Shelley and Vitality, which more generally considered Shelley’s interest in science and medicine.

Davy was a friend of S. T. Coleridge, Maria Edgeworth, William Godwin, Robert Southey, William Wordsworth, and many other poets and novelists of the period. He was the first person to inhale nitrous oxide – when it was thought to be fatal to do so – and he did this in Bristol with a circle of radical figures. Anna Barbauld even tried it (and Davy appears in her poem Eighteen Hundred and Eleven), as did Peter Mark Roget, the physician who would write the Thesaurus. Davy isolated more chemical elements than any other person has before or since and he did this using the new science of electrochemistry, something that Shelley was extremely interested in.

At Oxford University, T. J. Hogg reported that Shelley possessed ‘an electrical machine, an air-pump, the galvanic trough, a solar microscope, and large glass jars and receivers’ with which to create various chemical and medical preparations. Hogg ridiculed Shelley’s vision of a galvanic battery of ‘colossal magnitude, a well-arranged system of hundreds of metallic plates’, but in doing so only revealed his own lack of scientific knowledge. Davy built such a battery, a pile of 2000 plates, with which to conduct his experiments. Davy was also the friend of Byron, meeting him in London and Ravenna, and indeed he wrote two poems about Byron, one written after he heard of Byron’s death. Byron immortalized the miners’ safety lamp that came to be known as the ‘Davy Lamp’ in Canto One of Don Juan, writing: ‘Sir Humphry Davy's lantern, by which coals / Are safely mined for’.

The Davy Lamp which saved countless lives.

Mary Shelley noted in her journal that she read one of Davy’s books almost every day in 1816. This is exactly when she was writing Frankenstein.

Laura E. Crouch, writing in the Keats-Shelley Journal in 1978 suggests the book she read was Davy's A Discourse, Introductory to a Course of Lectures on Chemistry. Crouch suggests this work accurately reflects "the scientific ideas presented in the novel and the scientific optimism that shaped the character of the young Frankenstein and thus led him to undertake his "monstrous" project. She also observed the similarities between Victor Frankenstein’s and Professor Waldman’s pronouncements on nature and the progress of modern science:

"The spirit of enthusiasm that Davy conveyed to his fashionable London audience was the same spirit that led Frankenstein to begin his scientific experiments. The feeling of awe concerning the potential for scientific discovery was excited in Frankenstein during the introductory lecture to M. Waldman's course in chemistry at the university at Ingolstad." (38)

Davy and his wife, like most English aristocrats of their time were well aware of second generation romantics like Shelley and Byron. And we have some indication of what they thought of them. We have, for example, a letter from Sir Humphry’s wife to friends in Geneva written during the summer of 1816. This was the so-called “year without summer” and the year when Byron and the Shelleys had taken up summer residence at the Villa Diodati across the lake from Geneva.

The Villa Diodati

Clearly word of the allegedly scandalous behavior at the Villa had travelled to London because Lady Davy wrote to her friends alluding to it. She wrote:

‘I conclude all our late publications have reached you, from the very many English who must have lately been at Geneva. (some of them say little for our morality or good nature, & indeed that Readers of Libel & Indecency scarcely escape the weight of censure due to the Authors. Helenism is our last poetical flower, neither very potent nor sweet in my opinion; but Sir H’s sentence on its merits is very favourable & & he may be more just.’

Lady Davy was clearly unimpressed by the kind of poetry being written by the Shelley-Byron circle (which she curiously refers to as “Helenism”), whereas, as she admits, Davy was more in its favour – “his sentence on [meaning opinion of] its merits is very favourable…” I am sure that such a verdict from someone they so highly respected would have gratified Percy and Mary. It is uncertain whether Davy ever actually met Percy and Mary, though they were in Rome at the same time in April 1819 (Shelley arrived in Rome on 5th March 1819 and left Rome on 10th June), but if they had it seems likely they would have had lots to talk about.

The online course ‘Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp’ will explore some of the many connections between Davy and the Romantic poets. We will look at Davy’s relationship with key writers of the day such as Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, Byron and Coleridge. Perhaps the most innovative thing about the course is the emphasis it gives to Davy’s poetry: many of his poems can be read and heard on the course. Davy will be considered as a Romantic poet himself, and his poems on Mont Blanc, Cornwall, ‘genius’, and ‘life’ put into this context for all to enjoy.

You can buy Sharon's book, Shelley and Vitality, here:

I heartily recommend buying this book from your local bookseller. Just send them this link and ask them to order it for you. Support your local community.

David, or The Modern Frankenstein: A Romantic Analysis of Alien: Covenant by Zac Fanni

I was very excited to hear that Shelley's poem Ozymandias features prominently in the new movie in the Alien franchise: Alien: Covenant. The poem's theme is woven carefully into the plot of the movie, with David (played again by Michael Fassbender) quoting the famous line, "Look on my works ye mighty and despair." What immediately drew me to Zac Fanni's excellent article was his discussion of the Ozymandias scene. However, what I found amounted to so much more. We are offered a kaleidoscopic array of classic romantic allusions including some which are more obvious, for example Frankenstein and Rime of the Ancient Mariner; and some that are decidedly less so: Shelley's Alastor makes an unexpected appearance!

I was very excited to hear that Shelley's poem Ozymandias features prominently in the new movie in the Alien franchise: Alien: Covenant. The poem's theme is woven carefully into the plot of the movie, with David (played again by Michael Fassbender) quoting the famous line, "Look on my works ye mighty and despair."

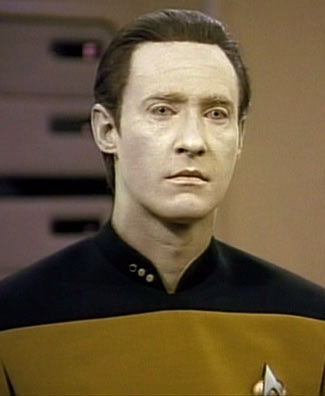

David, as followers of the movies will know, is a xenomorph - a "synthetic humanoid" - one in a long line of such creatures, one of the most famous being Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation.

That David quotes the poem without a trace of irony is central to the question of whether or not these creatures are fully human or not. For David not to see that Shelley is employing one of his trademark ironic inversions, suggests that something is not quite right with him. That he mistakenly attributes the poem to Byron is another twist altogether.

What immediately drew me to Zac Fanni's excellent article was his discussion of the Ozymandias scene. However, what I found amounted to so much more. We are offered a kaleidoscopic array of classic romantic allusions including some which are more obvious, for example Frankenstein and Rime of the Ancient Mariner; and some that are decidedly less so: Shelley's Alastor makes an unexpected appearance!

Now, does this make the movie an expression of Shelley's philosophy or values? Alas no. The movie strikes me more as an empty repository of romantic motifs and riffs than anything else. Some of these are undoubtedly extremely clever, others are surely accidental or unconscious. The philosophy which underpins the movie is one of profound cynicism and nihilism. Shelley was a skeptic, not a cynic and certainly not a nihilist. As Paul Foot observed, "It’s very, very easy for the skeptic to topple over into being a cynic. And a cynic can never be a revolutionary. [It is] absolutely impossible for a cynic to be a revolutionary because they don’t see the possibilities - they don’t believe that it’s possible that working people can change their lives and change society." Read more about this here.

One point of overlap between the many Alien movies and Shelley is that women take the lead. Foot observed this of Shelley when he wrote, "All through Shelley’s poetry, all his great revolutionary poems, the main agitators, the people that do most of the revolutionary work and [who he gives] most of the revolutionary speeches, are women. Queen Mab herself, Asia in Prometheus Unbound, Iona in Swellfoot the Tyrant, and most important of all, Cyntha in The Revolt of Islam." In the case of the movie franchise we have Alien's Ripley (Sigorney Weaver), Prometheus’ Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and Covenant’s Dany Branson (Katherine Waterston). These are all strong women, but there the similarities end. Shelley imagines his female leads as engaged in important revolutionary work, they are gradually but inexorably changing the world for the better. The same is not true of Ripley, Shaw or Branson, as Fanni himself notes. Ripley makes a lonely, solitary escape, while the other two die miserably in the grasp of an overweening, inexorable fate. This is distinctly un-Shelleyan.

But what about the links to Alastor? Certainly, I think we have to take as a starting point that not one single person connected with the movie has ever read or even heard of Alastor. But that does not mean that the themes of Alastor do not resonate, and Fanni makes a very compelling case for this. Roland Duerksen, in his short but brilliant book, Shelley Poetry of Involvement, makes the point that 'Shelley's art always brings us round to a direct confrontation of what it really means to live - which for him is synonymous with really to love." Fanni's version of this is this: "In “Alastor,” Shelley shows us our two conditions: first, that the poverty of our language and imagination causes us to be deeply, metaphysically anxious about our nature; and second, that pursuing answers to these mysteries entails transcending the self, a form of death where you become part of the great design."

The term "alastor", which suggests a pursuing vengeful spirit, was suggested to Shelley by his friend Thomas Love Peacock. Duerksen's conclusion is, therefore, that Shelley must have thought of "separateness or alienation" as that just that vengeful spirit. Very clearly alienation and separateness are one of the central themes of Covenant, indeed all of the Alien movies. The difference, however, between David and the young poet of Alastor, is that the latter aspires to be something more. That he fails is the tragedy of the poem. And he shares a fate very different from that of David in Covenant - he dies. Duerksen describes the poet's "propensity toward unloving, isolated existence" as his great failing. Had he detected it earlier he would have awakened to the potential for what Duerksen calls "human, imaginative identification" with the world.

David, on the other hand, seems to revel in his isolation, learns nothing from it and yet ultimately triumphs. Whereas Shelley extols the maternal power of nature in Alastor, in the world of Covenant, David has absolutely overmastered nature; in fact almost sterilizing it. In one of the great passages from A Defense of Poetry, Shelley contends that love "is an identification of ourselves with the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own." In other words, love is empathy. He later defines imagination as the act of putting oneself in the "position of another." Empathy again - or what Duerksen calls "involvement". The world of Covenant is utterly devoid of any empathy whatsoever and David is utterly lacking in imagination. The xenomorph learns virtually nothing from his exposure to humans. This point is brought home in what Fanni calls "One of the most disturbing moments of the film," which, he continues, "involves no aliens at all: our protagonist, Dany Branson is physically overpowered by David, who bends over her with a pantomimed kiss, threatening sexual violence by whispering, “Is this how it is done?” No empathy, no identification with the other and no imagination. Just the horror of the vacant abyss of self-involvement.

The principal difference between the young poet of Alastor and David is that the poet at least attempts, as Duerksen says, to expel "solitude and silence, replacing them with imaginative union and creative expression." The message of Alastor is ultimately hopeful and uplifting. And the full flowering of this optimism came later in in poems such as Prometheus Unbound and The Triumph of Life. We can see the possibility for growth and development. On the other hand, Covenant presents us with a nihilistic vision almost completely devoid of the possibility for human redemption.

So my conclusion is that while Covenant has many roots in the world of the romantic poets (as Fanni has so ably demonstrated) its fruit is poisoned, sterile and antithetical to everything dear to that world, and in particular to Shelley.

Zac Fanni is a Toronto-based freelance writer and college professor teaching in the Humanities. He tells me he is convinced of two things: that Penny Dreadful is the best television show to have ever aired, and that he will one day get a tenured position at Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters. Both of these things, he says, are probably unlikely. You can find him on twitter here, and on Youtube here.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green,

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—Like one, that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread. (442-451)Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Dread is the fear that lingers, the fear that condenses into an apprehension so tangible that it becomes a part of our environments: once the literal visage of death has been witnessed (in the female, male or double-mawed alien form), the mariner’s ship, the scientist’s laboratory and the space jockey’s stasis pod all become stained and saturated with its horrific presence. This is what 1979’s Alien achieved so thoroughly: it made the familial warmth of the Nostromo’s cafeteria congeal into an intimate terror of a subliminal nightmare birthed from the human body.

Part of the perfection of Alien lies in its totality, as it is a film that needs no sequel, no franchise, no epilogue to Ripley’s final log entry. And while we received the obnoxiously competent Aliens, the resulting entries have deadened us to our beloved xenomorph. Yet with the brave and imperfect Prometheus, Ridley Scott’s creatures became more than a perfected source of physical dread–they emerged as the grotesque manifestations of our deep existential dread about our origin, mortality, and meaning. Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), founder of the company that launches the franchise’s ill-fated missions, opens Alien: Covenant by asking the “only question that matters: Where did we come from?”

As it was with the xenomorph in the previous films, the dread surrounding this question begins with an encounter: the archaeological depictions of alien visitations that form the opening shots of Prometheus both inspire and foreshadow the film’s central quest, a quest that ends when Peter Weyland is bludgeoned to death by the creator he spends his life searching for. This demise provides us with a secularized version of humankind’s fall in Milton’s Paradise Lost, where mankind, seeking godhead, loses all. Killed by his search for immortality, a search that is decidedly male in this franchise (our female heroes avoid this kind of solipsism), Weyland whispers, “there’s…nothing.” It is David (Michael Fassbender), Peter’s android “son,” who alone realizes the dark irony: the questions that matter have no answers. David responds to those final words by telling his creator-father, “I know.”

Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant brilliantly steps forward from this point by focalizing the familiar “Jaws in space” story around the lost android of Prometheus. In Covenant, David is a mythopoeic creature whose knowledge of the metaphysical nothingness lurking just beyond our comprehension drives him to create an answer for it. In the process, David becomes both Frankenstein and his creature (finalizing the series’ chain of created beings who seize that Promethean power for themselves), Milton’s Satan (preferring to reign in his necropolis than serve in civilization), and an unironic version of Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias (commanding his victims to “Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” while creating and using the “lone and level sands” that surround the shattered remains of those endeavors) (11, 14). And while the film’s trailers tell us directly that “the path to paradise begins in hell,”it is their encounter with its ruler that hints at the horrifying truth: there is no paradise to ascend to.

By using David’s metamorphosis to frame the familiar transmogrifications suffered by the Covenant’s hapless crew, Alien: Covenant presents a horrifying inversion of the Romantic pursuit of the sublime – not only are there no meaningful answers to our deepest questions, but the very pursuit of those answers consumes us from the inside out, leaving a literal manifestation of Frankenstein’s “wrecked humanity” to float alone in void of space (Shelley 165). Our survivors, like Coleridge’s Mariner, are condemned to forever “walk in fear and dread” as they recount their tale to reluctant, doomed ears. If, as Percy Shelley wrote, poets “measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature” (850), David does so to the point of nihilism: he reveals that those depths are empty and capable of reflecting back an inner (and literal) monstrosity.

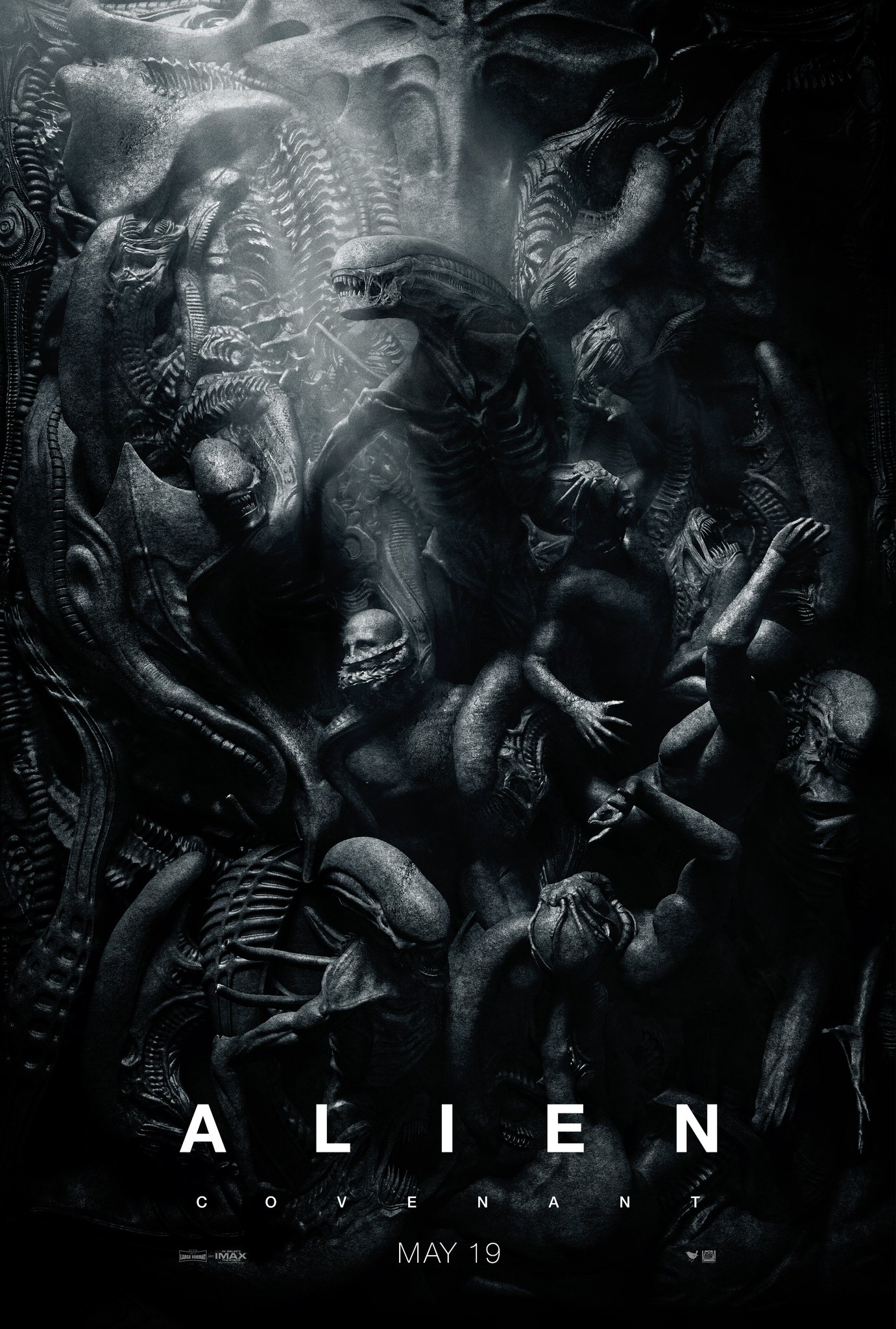

Before we are even exposed to the film itself, the metaphysical dread of Alien: Covenant is prefigured in its marketing. Consider what might just be the best film poster of the year:

The poster retains the inky corporeality of an engraving print, and visually signifies the inverted ascension that becomes the central motif of our prequel films: the xenomorph emerges triumphantly into the sole source of light, atop the suffering, subdued bodies that evoke Giovanni da Modena’s depiction of Dante’s Inferno. These neoclassical figures (where specific personalities are eschewed in favor of an “ideal” human form) also imply a universality–these aren’t characters from the film or franchise, but bodies that instead represent humanity as a category.

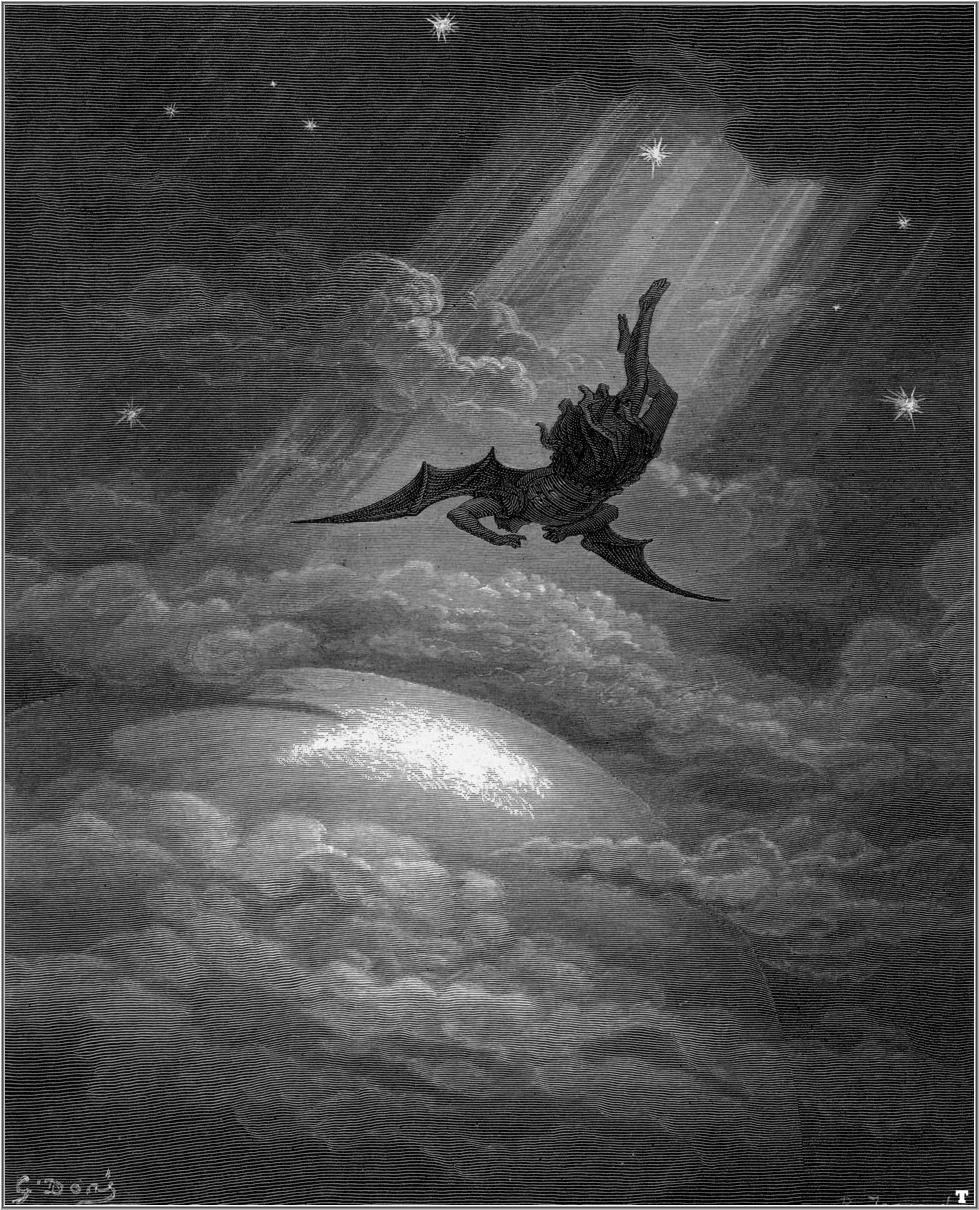

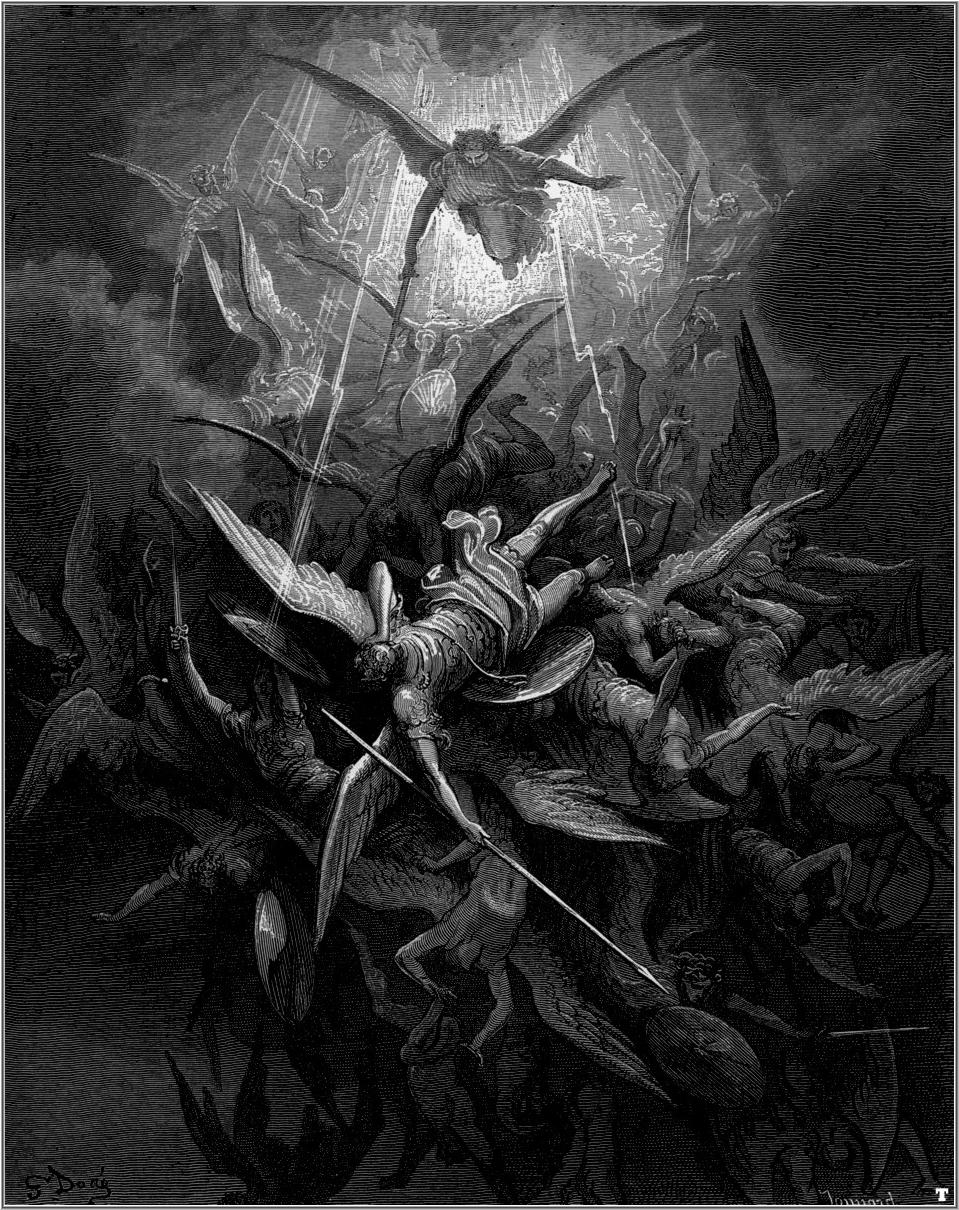

There are innumerable parallels that can be drawn with this image, but Gustave Doré’s engravings for Paradise Lost provide a strong starting point of comparison, especially considering that Ridley Scott once claimed that Alien: Paradise Lost would be the name of the Prometheus sequel. Let’s examine these two illustrations in particular: the first depicts archangel Michael casting Lucifer and his fallen angels out of heaven (1.44-45), while the second depicts Lucifer hurtling towards Earth, eager to corrupt Man and his realm (3.739-41).

In our first illustration [on the right], the vertical arrangement is more traditional: good triumphs, literally, over top evil, with the light source both illuminating the sacred and casting the profane into shadow. In other words, it is the opposite of Alien: Covenant’s poster arrangement, where there is no cosmic ideal to represent–all that exists is a darkness within humankind that emerges into the light, a twisted creature that erupts from the subliminal spaces of our minds and bodies.

In the second illustration [on the left], Satan descends from the heavens to corrupt humankind, God’s new (and perfect) creation. The source of light again both locates the heavens in a more literal way, and (again) frames Satan in contrast to the sacred ideal (the contrast between his dark figure and the heavenly light is particularly extreme), making his descent a direct personification of the Fall (from grace, perfection, etc.) soon suffered by prelapsarian humanity. Again, Alien: Covenant represents an inversion of this motif: evil is not something that arrives from without, but is something that violently, inescapably erupts from within ourselves and as our selves. The nothingness that the franchise’s expeditions seek to confront, the nothingness that Peter Weyland faces as a reward for his life’s labors, is what makes monstrosity possible: seeking to close that existential void engenders our fall, allowing a figure of pure, savage atavism to emerge in our place.

It is no coincidence that Paradise Lost figures heavily in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein–Milton’s poem is the very text through which Victor Frankenstein’s creature comes to understand his own monstrosity. Understandably, the creature identifies with Milton’s Satan, seeing Lucifer as the “fitter emblem” of his condition, and he even envies the fallen angel, telling his creator, “my form is a filthy type of yours, more horrid even from the very resemblance. Satan had his companions, fellow-devils, to admire and encourage him; but I am solitary and abhorred” (132, 133). While the abhorred form draws an obvious parallel to the xenomorph (whose human resemblance constantly reminds us of our bodies’ horrendous mutability), the creature’s more likely analogue in Alien: Covenant is David; what figure other than the android has taken a more coveted place in our collective imagination, precisely because its resemblance to us (in both a physical and metaphysical sense) disrupts our sense of what we are? Our ontological uniqueness, in other words, is threatened by the humanity that can be created.

If you decide to use some sort of Voight-Kampff test to determine your subject’s humanity, the eyes would make for an intuitive starting point – as in Blade Runner, Alien: Covenant features an extreme close-up of a (human?) eye, which we soon realize is David’s. Eyes are an obvious symbolic starting point, as they are the simultaneously the site of both empathy and expression: we observe the subjectivity of others while revealing our own. When characters shield their eyes (as, for example, agents do in the Matrix films), it is a clear symbol for soullessness. This is no different in Mary Shelley’s novel. Victor Frankenstein, after a seemingly fruitless toil to “infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing” before him, sees “the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.”

The creature’s eyes signify his life, but also a life that is cast as nonhuman: “the dull yellow eye” reflects an ontological dullness imposed by Frankenstein, who labels the creature as a ‘monster’. It is no mistake that Frankenstein keeps returning, almost obsessively, to the creature’s eyes: he notes that the “luxuriances” of the creature’s lustrous hair and pearly-white teeth only form “a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes,” and when the creature seeks Frankenstein’s company by invading his bedroom (a scene of horrific, tragic proximity perfectly captured by Bernie Wrightson in his comic book adaptation of the novel), Frankenstein notes that the creature’s “eyes, if eyes they may be called, were fixed” on him. It is only the creature’s words that inspire compassion from Frankenstein, who narrates that the creature’s story of profound, imposed loneliness (itself a tragic version of the Romantic preference for isolated contemplation) “had even power over my heart” (58, 59, 212).

The creature’s experience is shared by our own version of him: the android. David’s perfect diction, posture and figure (which Billy Crudup’s character threatens to “fuck up” in the film) are “luxuriances” that only call attention to his nonhuman ontology. As with Frankenstein, it is our proximity to our created entity that shatters our metaphysical preconceptions and causes us to be deeply unsettled: “now that I had finished,” narrates Frankenstein, “the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” Victor is “unable to endure the aspect of the being” that he creates (58), and it is this proximate encounter that causes him to flee into the rain-drenched street of Ingolstadt, reciting Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” to express the dread that pushes him forward (“on a lonesome road”) while preventing him from looking back (446).

Likewise, David’s uncanny humanity (his creepiness factor goes unchecked in Alien: Covenant) propels us away, and the entire plot of the film’s latter half is moved forward by escalating scenes of discoveries about David’s experimentation and intention. One of the most disturbing moments of the film involves no aliens at all: our protagonist, Dany Branson (played impeccably by Katherine Waterston), is physically overpowered by David, who bends over her with a pantomimed kiss, threatening sexual violence by whispering, “Is this how it is done?” This is Covenant’s version of the creature’s bedroom invasion in Frankenstein, replete with threat of sexual invasion endemic to the Alien films. David not only calls direct attention to his uncanny difference, but also construes that difference as a threat.

It is this knowledge of the human-like creature gained from this kind of close encounter that causes the heart to palpitate in the “sickness of fear” (Shelley 60). Even the word ‘monster’, a word used by Frankenstein against the creature and a word that is often thrown at our ‘malfunctioning’ androids, is rooted in the Latin word monstrum, meaning to exhibit, or make known. The most horrific monsters, therefore, are the ones that are familiar to us – Frankenstein’s creature, David the android, and the xenomorph terrify us because our proximity to them reveals the similarities that accentuate their differences, making them an unsettling (and often direct) threat to our sense of self. We feel as if we have no choice, and cast them out into the “deep, dark, deathlike solitude” found in the wilderness, or on a barren planet, or in the depths of outer space (93). In this way, the disfigurement suffered by Frankenstein’s creature and David is ontological, in that we reject their subjectivity, finding ourselves unable to accept their facsimiles of humanity. Frankenstein, for instance, warns Captain Walton (Victor’s rapt listener) that the creature’s “soul is as hellish as his form, full of treachery and fiendlike malice,” which may be a more accurate description of David than it is of the tragically spurned creature (212). Even David’s confrontation with his ‘brother’ Walter (the ‘improved’ version of the android accompanying the Covenant crew) is itself an encounter that accentuates difference through similarity, and David (like Frankenstein) finds the reflection of his own identity unpalatable. Before attempting to murder him, David says to Walter, with a kiss, “No one will ever love you like I do.” It is precisely because David understands Walter so well that he is driven to destroy him – in Walter is everything David is threatened by (i.e. amenable, claustrophobic servitude), just as we see in the android the metaphysical emptiness that threatens us. David condemns Walter, his mirror image, as thoroughly as we condemn the humanlike figure resurrected in the android.

Whether human or android, encounters with created beings prompt your own existential anxieties – you become akin to Frankenstein’s creature, asking yourself unanswerable questions: “What does this mean? Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination?” (131). Alien: Covenant replicates this likeness directly: humanity discovers itself to be the creation of beings who seem to find us monstrous, in that they find us to be a dreadful mimicry of themselves, and we thus share in the experience of the android, wondering about a greater meaning that must lie somewhere out in the vast infinity of space. And, as we witness during Peter Weyland’s final scene in Prometheus, the answer to these questions is a nihilistic one: there is nothing awaiting the search for our origin, identity and meaning. These recurring questions, as Frankenstein’s creature finds out, are “answered only with groans” (124).

While David is aware of this metaphysical nothingness in Prometheus, evoking the absurdist irony at the heart of humanity’s quest for meaning, he is also responsible for unleashing it in both Prometheus (where he infects Charlie’s drink with the seemingly omnipotent alien gel, leading to the brilliantly twisted med-pod birth scene) and Alien: Covenant (where he creates a literal dark cloud of death that consumes all life on the planet). And while the ‘inky death cloud’ bio-weapon causes us, perhaps understandably, to bemoan a lack of creativity in the film, it does function as a clear metaphor: the dark nothingness awaiting our most urgent questions is not just a vacuum in this franchise, but a dreadful entity waiting to possess and mutilate our very being. And David, whose non-humanity inoculates him against this darkness, is the ‘person’ who emerges capable of fashioning an answer to this void: he seeks to create “the perfect organism.” David is not just a Frankenstein creature to be abhorred as a monster – he is Frankenstein himself, a being obsessed with creating a “new species” who would exalt him “as its creator and source.” And, again, this obsession is really an inversion of that pursuit: while Frankenstein imagines that “many happy and excellent natures would owe their being” to him (55), David imagines a creature who, to use the words of his fellow android, is “perfect” in its “purity. A survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

This is the Alien franchise’s version of the Romantic pursuit of the sublime, a word that shares its Latin root with ‘subliminal’: limus (muddy, oblique) and limen (threshold, limit). To the Romantics, the sublime was an experience of the incomprehensible, an experience of crossing the threshold of human understanding and transcending the boundary of the intelligible. Edmund Burke cites this experience as a form of “astonishment,” which includes feelings of terror and despair–beholding nature’s vast wonders, for example, inspires a sensation of existential terror where we realize our smallness and insignificance in relation to the cosmic forces that shape our world. The poet John Keats termed this our “negative capability”: experiencing, or “being in,” mystery without trying to use our reason to entrap or solve it (194). For the Romantics, this paradoxical conception of the inconceivable is, to borrow Wordsworth’s phrase, a way to actively engage with the burdens of “all this unintelligible world” (40). Published alongside “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” in Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” cites the speaker’s debt to the “forms of beauty” bestowed by nature:

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world

Is lighten’d:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame,

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things. (37-49)

This recollection of beauty, an experience of the ineffable power surrounding us, allows the speaker to transcend the self and touch the periphery of infinity – the speaker approaches that eternal sleep of death, where blood almost stops flowing, to become a “living soul” that takes part in the greater “life of things.” This transcendent experience becomes the “anchor” of the speaker’s “purest thoughts,” forming the “soul” of all his “moral being” (109-111).

20th Century Fox

This is precisely the “moral being” formed by Frankenstein’s creature in Shelley’s novel, where we are provided with an almost evolutionary account of the human experience: the creature is first subject to “a strange multiplicity of sensations,” then discovers and learns the “godlike science” of language, and finally refines his understanding through literature. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives and Milton’s Paradise Lost teach the creature about the experience, language, and history of the human condition. This experience and exploration of the sublime, however, does not lead to a harmonious suspension of self. Instead, the creature is afflicted with an indescribable agony, where his “sorrow [is] only increased with knowledge.” This causes the creature to wish to “shake off all thought and feeling,” which comes from the ability to see himself, for the first time, as a monster, “a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled.” The sublime is also lost to Victor Frankenstein, who throughout the novel grows increasingly akin to his creature – again showing that our creation of other beings precipitates a deeply unsettling disruption of identity. Victor’s experiment causes him to see himself as a “miserable spectacle of wrecked humanity,” where “the sight of what is beautiful in nature” and the experience of what “is excellent and sublime in the productions of man” hold no refuge (105, 115, 123, 165). Thus Frankenstein, like many of the Alien films, explores the human destruction that occurs when there is a collapse of the aesthetic distance between the self and the sublime – grasping the incomprehensible, in all its terror, beauty and power, is an annihilating experience without that distance. Without it, Wordsworth’s sleep-like suspension becomes mortally final: our identities and bodies are obliterated by forces as unceasing as they are insatiable, as devoid of remorse as they are of morality.

Alien: Covenant is similarly occupied with this kind of collapse–the xenomorph is a “perfected” personification of those amoral, perennial forces. However, David’s pursuit of the sublime, of that “perfect organism,” is not a process that destroys him as it does Frankenstein, to reveal a lesson about the perils of aspiring to godhead (the sin that afflicts both Satan and humankind in Paradise Lost). Rather, it is David’s ‘other’ ontology, the fact that his identity is not unitary, that allows him to face the indifferent, annihilating forces behind the “the life of things” and use those forces for his own ends. With David, there is nothing to dismantle. Again, he acts as a Frankenstein figure even while he inverts it: unlike the Covenant and Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory, spaces that build the hope and possibility for new life, David’s spaceship contains only the promise of death and oblivion. As a dark inversion of the Romantic poet, David does not seek the sublime as an end. He seeks instead to harness it as an answer to the nothingness rotting at the heart of human existence. And in creating the xenomorph, David’s response seems clear: if nothingness awaits us at the end of all this spiritual, existential yearning, what use is the ability to ponder it? Our thoughts, our anxieties, and our very cultures, are centered around an aimless, purposeless striving that clouds our natures as organisms.

In executing his vision, David doesn’t just embrace the pride of Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias, commanding all of life to behold his terrible works, but also enacts and seizes the “colossal Wreck” around which the “lone and level sands stretch far away” (13-14). David’s necropolis is the ruin from which he builds his xenomorph, and both feel like grotesque expressions of subliminal fears and anxieties (H.R. Giger’s presence is heavily felt in Alien: Covenant, and the necropolis seems to be heavily derived his work on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune). In this way, David acts as the speaker of Percy Shelley’s Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude, itself a poem about a poet’s relentless pursuit of the sublime.

The speaker claims to be ever gazing “on the depth” of nature’s “deep mysteries,” and says,

I have made my bed

In charnels and on coffins, where black death

Keeps record of the trophies won from thee,

Hoping to still these obstinate questionings

Of thee and thine, by forcing some lone ghost

Thy messenger, to render up the tale

Of what we are. (23-29)

Percy Shelley has his speaker recognize that examining the causes and conditions of life requires, in the words of Frankenstein, a “recourse to death” (Shelley 52). In “Alastor,” Shelley shows us our two conditions: first, that the poverty of our language and imagination causes us to be deeply, metaphysically anxious about our nature; and second, that pursuing answers to these mysteries entails transcending the self, a form of death where you become part of the great design. David offers a horrific inversion of this: he knows that nothing lies at the heart of these mysteries, which exposes the vanity and absurdity of the human expeditions he is a part of, and he uses this metaphysical void to create a being that personifies and perfects the terror at the heart of the sublime. The helplessness one feels when beholding nature’s majesty becomes a literal, fatal helplessness in the face of a perfected hostility.

This is what makes the final scene of Alien: Covenant so disturbing: David places the embryos of his creation alongside the human embryos of the Covenant, collapsing the distance (in a very literal and necessarily fatal way) between humanity and the ineffable forces that move like leviathans at the very edge of our experiences. David is thus literalizing and accentuating the doom that awaits all human beings, a doom that is engendered at birth. And instead of escaping from or clarifying that condition, we have allowed it to invade our most intimate spaces. This is the deep nihilism that the Alien prequels rest upon, as each of our female protagonists (Prometheus’ Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and Covenant’s Dany Branson) do not share in Ripley’s hopeful, if solitary, escape. Both Elizabeth and Dany are forced to rest in full view of the horror that has pierced the veil, the gaping maw that greets their most profound questions. In this way, the final scenes of both Prometheus and Alien: Covenant are perfectly captured by the speaker’s final words in Shelley’s Alastor: after recounting the inevitable death of the poet who strove for the sublime and was lost in that “immeasurable void” (a permanent, troubling version of Wordsworth’s sleep-like suspension), the speaker notes:

It is a woe too “deep for tears,” when all

Is reft at once, when some surpassing Spirit,

Whose light adorned the world around it, leaves

Those who remain behind, not sobs or groans,

The passionate tumult of a clinging hope;

But pale despair and cold tranquillity,

Nature’s vast frame, the web of human things,

Birth and the grave, that are not as they were. (713-720)

For Alien: Covenant, the spirit that leaves, the spirit that adorns the world with its light, is the empty specter of spiritual, metaphysical wholeness. It is no coincidence that both prequel films have deeply religious characters who lose (or at least conflict with) their faith: there is no hope to cling to in such a universe, just the “pale despair” and “cold tranquility” of “Nature’s vast frame.” There is nothing to return to–the constants by which we measured our lives “are not as they were,” and our female heroes depart each film heavy with this knowledge. This has always been the deeply horrific epilogue of the Alien franchise: our surviving woman, weighted by her encounter with the perfect monster, retires from the unceasing struggle unsure if she will survive the night.

Zac Fanni is a Toronto-based freelance writer and college professor teaching in the Humanities. He tells me he is convinced of two things: that Penny Dreadful is the best television show to have ever aired, and that he will one day get a tenured position at Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters. Both of these things, he says, are probably unlikely. You can find him on twitter here, and on Youtube here. This article was originally published by http://www.audienceseverywhere.net and was reproduced with their kind permission. If you wish to view the original article you can find it here.

Sources

- Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Harvard Classics, vol. 24, part 2, 2001, http://www.bartleby.com/24/2/. Accessed 20 May 2017.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The Norton Anthology of EnglishLiterature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W.Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 430-446.

- Doré, Gustave, illustrator. Paradise Lost. By John Milton. Arcturus, 2005.

- Keats, John. The Letters of John Keats: Volume I. Edited by Hyder Edward Rollins, CambridgeUniversity Press, 1958, pp. 193-94.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “A Defence of Poetry.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 837-850.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 745-762.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Ozymandias.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, 768.

- Wordsworth, William. “Lines Composed A Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour, July 13, 1798.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 258-262.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the British Association for Romantic Studies' the ‘On This Day’ blog. Anna discusses P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ and the inclusion of this poem in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. You can find the original post here.

I think this is an extremely important addition to the Guest Contributors series because it introduces the concept of collaboration. When I was a student in the 1970s and 80s, the idea that Mary had meaningfully collaborated with Shelley* on anything was unheard of. Indeed, the extent of Shelley's involvement in Frankenstein was poorly understood. The modern era has been, however, exceedingly kind to Mary and rather less so for for Shelley. As I have alluded to elsewhere, undergraduates around the world can be forgiven for being literally unaware of a personage by the name Percy Shelley; Mary is all anyone seems to talk about. While on the one hand this may be seen as an much overdue re-balancing of the scales of history, on the other it might be thought of as over-kill. This is where Anna comes in, guiding us through the complicated waters of one of the most interesting literary partnerships in the English language.

I think that today no one should approach the poetry of Shelley without understanding that these two creative people without question influenced one another. This will be a topic for one of my own blogs in the coming months, and I hope Anna will allow me to publish more of her work in this area in the future. Now, an area where Anna and I might disagree would be on the question of whether this poem offers evidence of philosophical idealism. My belief is that even by 1815, Shelley was such a thorough-going philosophical skeptic (in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Drummond) that this is doubtful. This is, however, a quibble, and with that thought, let's turn to one of the modern experts on the subject of Shelleyan collaboration, Anna Mercer.

* A note on my choice of names. For most of the past two centuries, it has been common to refer to Mary Shelley as "Mary" and Percy Shelley as "Shelley". More recently many writers, such as Anna, now refer to them both by their given names. For my part, what matters is that fact that this is the manner in which they invariably referred to one an other; and so I stick with the old ways. I hope this will offend no one.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, from portraits in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!--yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost forever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest.--A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise.--One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!--For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ is an example of his extraordinary poetic talent; in particular these lines show his ability to weave together philosophical ideas and striking imagery within a short section of verse. In this way the poem is reminiscent of Shelley’s famous sonnets such as ‘Ozymandias’ and ‘England in 1819’. However, ‘Mutability’ was written before these other works, which were composed in 1817 and 1819 respectively. The exact date of composition for ‘Mutability’ is not known: the editors of the Longman edition of The Poems of Shelley assign it to ‘winter 1815-16 mainly on grounds of stylistic maturity’. However, the opening lines ‘suggest a late autumn or winter night, but this could have been equally well a night in 1814’.

The ‘On This Day’ blog series thus far has focused on the bicentenaries of events from 1815: if the most likely dating for ‘Mutability’ places its composition in the winter of 1815, the poem must have lingered in the mind of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who would include lines from ‘Mutability’ in Chapter II, Vol II of Frankenstein (1818). Mary Shelley did not begin writing this novel (her first full-length work) until the summer of 1816, which she spent with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John William Polidori in Geneva.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. Mont Blanc and the Glacier des Bossons from above Chamonix, dawn 1836.

It is interesting that we see Percy Shelley’s maturity emerging in ‘Mutability’, as the editors of the Longman Poems of Shelley establish. This maturity can be understood as Shelley’s fine-tuning of his philosophical expressions into a more coherent idealism. The poem’s almost universal application to any ‘man’ who lives on to the ‘morrow’ may be why Mary Shelley chose to place two stanzas (ll.9-16) in her first novel. They appear just before Victor Frankenstein reencounters his creation for the first time since its ‘birth’. He sets off on a precipitous mountain climb to the glaciers of Mont Blanc – alone – in an attempt to combat his anxiety and melancholy state of mind:

The sight of the awful and majestic in nature had indeed always the effect of solemnizing my mind, and causing me to forget the passing cares of life. I determined to go alone, for I was well acquainted with the path, and the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene.

Victor’s view of the valley, the ‘vast mists’, and the rain pouring from the dark sky, prompt him to lament the sensibility of human nature. As in P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’, the narrator considers the inconstancy of the mind. This meditation presents a powerful contradiction that inspires both hope and hopelessness by reminding the reader that a potential for change is always present, whether fortunes be good or bad, whether the individual is positively or negatively affected by his/her surroundings. Either way, all might be completely altered over a short space of time as the human mind responds to external influences. Just as Percy Shelley writes ‘Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; / Nought may endure but Mutability’, Mary Shelley’s protagonist considers how ‘If our impulses were confined to hunger, thirst, and desire, we might be nearly free; but now we are moved by every wind that blows, and a chance word or scene that that word may convey to us’. Lines 9-16 of Shelley’s poem are inserted in the novel after this sentence. Percy Shelley read and edited the draft of Mary’s Frankenstein, and Charles E. Robinson (editor of the Frankenstein manuscripts) has described the possibility of the Shelleys being ‘at work on the Notebooks at the same time, possibly sitting side by side and using the same pen and ink to draft the novel and at the same time to enter corrections’. The inclusion of the lines from ‘Mutability’ could even have been a joint decision.

Sir Walter Scott’s favourable review of Frankenstein from 1818 (when the novel was published anonymously) assumes this poetical insert to be the same authorial voice as its surrounding prose: ‘The following lines […] mark, we think, that the author possesses the same facility in expressing himself in verse as in prose.’ But instead, the implication is that Mary’s prose seamlessly leads into Percy Shelley’s verse, and illustrates the unity of their diction and their collaborative writing arrangement at this time.

A page from Mary Shelley’s journal (1814) showing both Mary and Percy’s hands. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Mary Shelley’s journal shows that the Shelleys read S T Coleridge’s poems in 1815. Lines 5-8 of ‘Mutability’ indicate the possibility of a Coleridgean interest based on STC’s conversation poem ‘The Eolian Harp’. As Coleridge describes ‘the long sequacious notes’ which ‘Over delicious surges sink and rise’, Percy Shelley writes: ‘Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings / Give various response to each varying blast’. The Aeolian Harp or wind-harp (named after Eolus or Aeolus, classical god of the winds) is an image that reoccurs in Romantic poetry and prose. However it is significant that P B Shelley used it in common parlance with Mary, i.e. when writing letters. On 4 November 1814, he writes to her:

I am an harp [sic] responsive to every wind. The scented gale of summer can wake it to sweet melody, but rough cold blasts draw forth discordances & jarring sounds.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works. Beyond the Frankenstein notebooks, there are even instances of the Shelleys altering and/or influencing each other’s compositions in a reciprocal literary dialogue (something my work as a PhD candidate at the University of York is seeking to identify and explore in depth). If ‘Mutability’ was written in winter 1815 (or even earlier), maybe Mary Shelley looked over it, and kept it in mind in relation to her own creative writing – and therefore the poem found its way into her first novel. These details suggest that the Shelleys’ literary relationship was blossoming in the winter of 1815 (exactly 200 years ago), prior to their most significant collaboration on Frankenstein in 1816-1818.

References:

S. T. Coleridge, The Complete Poems ed. by William Keach (London: Penguin, 1997 repr. 2004) p. 87, 464.

Charles E. Robinson (ed.), ‘Introduction’ in Mary Shelley, The Frankenstein Notebooks Vol I (London: Garland, 1996), p. lxx.

Sir Walter Scott, ‘Remarks on Frankenstein’ in Mary Shelley: Bloom’s Classic Critical Views (New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008) p. 93.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: A Norton Critical Edition ed. by J. Paul Hunter (London: 1996 repr. 2012) pp. 65-67.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Mutability’ in The Poems of Shelley Vol I ed. by Geoffrey Matthews and Kelvin Everest (London: Longman, 1989) pp. 456-7.

William Godwin: Political Justice, Anarchism and the Romantics

Yet at least in the permanence of the printed word Godwin’s influence on Shelley remains. It is most apparent in Shelley’s political poems, which echo Godwin’s views on the state and his anarchistic vision of society.

Guest Contributors continues with Simon Court's brilliantly concise discussion of William Godwin's influence of the romantic poets. This account contains generous quotes from Godwin himself, and students of Shelley will no doubt hear much of Godwin in Shelley's poetry. But Godwin's influence was not limited to Shelley's political poetry, it can also be seen throughout Shelley's extensive philosophical prose.

Now having said that, it would be tempting to reduce Shelley's "intellectual system" to a rehashed amalgam of Godwin's thinking; many scholars have made this mistake. The fact is that while Shelley was influenced by Godwin, he a sophisticated philosopher in his own right - not an abject disciple. For example, Godwin had, as Simon points out, an incredibly "optimistic view of human nature." He quite literally believed that the world could be changed just by talking people into the change - no revolution required! He was a perfectibilist, and we can definitely see that tendency in the younger Shelley. But as Shelley grew in intellectual power, he came to see the world in a much more nuanced way.

As Terence Hoagwood points out, "Shelley advocates explicitly the active political displacement of [tyrannous structures] with another political structure: such a political advocacy is inimical to Godwin." (Hoagwood 6) Indeed, Prometheus Unbound also seems to point directly to some kind of revolution while veering away from any utopian resting place - both anathema to Godwin.

All of this is fodder for another blog post. For now, let's turn to Simon's account of Godwin's impact on Shelley and the Romantics. Remember: CONTEXT IS EVERYTHING!

William Godwin: Political Justice, Anarchism and the Romantics, by Simon Court

William Godwin, painting by William Henry Pickersgill

William Godwin was a major contributor to the radicalism of the Romantic movement. A leading political theorist in his own right as the founder of anarchism, Godwin provided the Romantics with the central idea that man, once freed from all artificial political and social constraints, stood in perfect rational harmony with the world. In this natural state man could fully express himself. This idea was first articulated in An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, published in 1793, and was immediately seized upon by Coleridge as an inspiration for his misplaced venture into ‘pantisocracy’. Later, it heavily influenced Shelley in his political poems.

Mary Wollstonecraft, by John Opie, 1797

Godwin’s impact was personal as well as intellectual. He married Mary Wollstonecraft, whose Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was one of the earliest feminist texts. He was good friends with Coleridge and later became the father-in-law of Shelley when his daughter, Mary, married the poet in 1816. Yet despite the idealistic ambitions of his principles, Godwin singularly failed to match up to them in his own life, behaving particularly hypocritically towards Mary and Shelley.

Godwin’s political views were based on an extremely optimistic view of human nature. He adopted, quite uncritically, the Enlightenment ideal of man as fully rational, and capable of perfection through reason. He assumed that “perfectibility is one of the most unequivocal characteristics of the human species, so that the political as well as the intellectual state of man may be presumed to be in the course of progressive improvement”. For Godwin, men were naturally benevolent creatures who become the more so with an ever greater application of rational principles to their lives. As human knowledge increases and becomes more widespread, through scientific and educational advance, the human condition necessarily progresses until men realise that rational co-operation with their fellows can be fully achieved without the need for state government. And, Godwin thinks, the end of the reliance on the state will also herald the disappearance of crime, violence, war and poverty. This belief in the inexorable perfectibility of man and progress towards self-government knew no bounds. Thus we find Godwin speculating that human beings may even eventually be able to stop the physical processes of fatigue and aging: for if the mind will one day become omnipotent, “why not over the matter of our own bodies….in a word, why may not man be one day immortal?”

On the other side of this sparkling coin lies the corrosive state, and here Godwin asserts that the central falsehood, perpetuated by governments themselves, is the belief that state control is necessary for human society to function. Rather, Godwin claims, once humanity has rid itself of the wholly artificial constraints placed upon it by the state, men will be free to live in peaceful harmony. For Godwin, “society is nothing more than an aggregation of individuals”, whereas “government is an evil, an usurpation upon the private judgement and individual conscience of mankind”. The abolition of political institutions would bring an end to distinct national identities and social classes, and remove the destructive passions of aggression and envy which are associated with them. Men will be restored to their natural condition of equality, and will be able to rebuild their societies in free and equal association, self-governed by reason alone.

Godwin’s utopian portrayal may be highly radical, but he was not a revolutionary. He believed political revolutions were always destructive, hateful and irrational – indeed, the immediate impulse to write Political Justice came from the murderous bloodshed in the recent French Revolution. And whilst Godwin never called himself an anarchist – for him, ‘anarchy’ had a negative meaning associated with French Revolutionary violence – his vision was recognisably anarchist. For Godwin, social progress could only be obtained through intellectual progress, which involved reflection and discussion. This is necessarily a peaceful process, where increasing numbers come to realise that the state is harmful and obstructive to their full development as rational creatures, and collectively decide to dissolve it. He was convinced that eventually, and inevitably, all political life will be structured around small groups living communally, which will choose to co-operate with other communities for larger economic purposes.

In addition to the artificial constraints placed on man by political institutions, Godwin identifies the private ownership of land, or what he termed “accumulated property”, as a major obstacle to human progress. And here, like all utopian thinkers, we find that Godwin’s criticism of the present reality proves to be far more convincing that his predictions of the future. For he observes that “the present system of property confers on one man immense wealth in consideration of the accident of his birth” whilst “the most industrious and active member of society is frequently with great difficulty able to keep his family from starving”. This economic injustice leads to an immoral dependence: “Observe the pauper fawning with abject vileness upon his rich benefactor, and speechless with sensations of gratitude for having received that, which he ought to have claimed with an erect mien, and with a consciousness that his claim was irresistible”. For Godwin, only the abolition of private property and the dismantling of the hereditary wealth which goes with it will free mankind from “brutality and ignorance”, “luxury” and the “narrowest selfishness”. Yet once freed:

Every man would have a frugal, yet wholesome diet, every man would go forth to that moderate exercise of his corporal functions that would give hilarity to the spirits: none would be made torpid with fatigue, but all would have leisure to cultivate the kindly and philanthropic affections of the soul, and let loose his faculties in the search of intellectual improvement. What a contrast does this scene present us with the present state of human society, where the peasant and the labourer work, till their understandings are benumbed with toil, their sinews contracted and made callous by being forever on the stretch, and their bodies invaded with infirmities and surrendered to an untimely grave?

In this utopia, or egalitarian arcadia, all the immoral vices of the present world, oppression, fraud, servility, selfishness and anxiety, are banished, and all men live “in the midst of plenty”, and equally share “the bounties of nature” – “No man being obliged to guard his little store, or provide with anxiety and pain for his restless wants, each would lose his own individual existence in the thought of the general good”, and “philanthropy would resume the empire which reason assigns her”. In this agrarian idyll, “the mathematician, the poet and the philosopher will derive a new stock of cheerfulness and energy from recurring labour that makes them feel they are men” (a world, incidentally, in which only “half an hour a day, seriously employed in manual labour by every member of the community, would sufficiently supply the whole with necessaries”).

Another highly radical idea raised by Godwin in Political Justice is the immorality of marriage. For Godwin:

“Co-habitation is not only an evil as it checks the independent progress of mind; it is also inconsistent with the imperfections and propensities of man. It is absurd to expect that the inclinations and wishes of two human beings should coincide through a long period of time. To oblige them to act and to live together, is to subject them to some inevitable portion of thwarting, bickering and unhappiness. This cannot be otherwise, so long as man has failed to reach the standard of absolute perfection.”

As such “the institution of marriage is a system of fraud”, and “the worst of all laws”. Moreover, “marriage is an affair of property, and the worst of all properties” (although this didn’t prevent Godwin marrying twice, first Mary Wollstonecraft in 1797 and then Mary Jane Clairmont in 1801). Inevitably, Godwin asserts, the institution of marriage will be abolished with all the other types of “accumulated property” in the new, free society. And although sexual relationships will continue because “the dictates of reason and duty“ will regulate the propagation of the species, “it will [not] be known in such a state of society who is the father of each individual child”, because “such knowledge will be of no importance”, with the “abolition of surnames”.

The vision of political society portrayed in Political Justice served as a direct and immediate inspiration for the Romantic ‘pantisocrats’ Coleridge and Southey, and contributed to their youthful flirtation throughout 1794 with the idea of migrating to North America to set up a rural commune (see Coleridge and the Pantisocratic pipe-dream). On a personal level, Coleridge first met Godwin and wrote the appreciative poem ‘To Godwin’ in 1794, but it was from 1799 onwards, when Godwin’s public reputation had waned, that they became good and mutually supportive friends (see Coleridge and Godwin: A Literary Friendship ).

By contrast, Shelley’s personal relationship with Godwin was far more turbulent: beginning in adoration but ending in despair. In 1811, Shelley started corresponding with Godwin, who was now a bookshop owner with a modest income, and offered himself as both an admirer and provider of financial support, which Godwin accepted in equal measure. A year later they met. Unsurprisingly, Shelley took Godwin’s pronouncements on marriage and ‘free-love’ to be a rational justification for him abandoning his first wife Harriet and eloping to Europe with Godwin’s sixteen-year-old daughter Mary, in July 1814. But Godwin reacted as furiously and as disapprovingly as any protective father would, and he refused to see Shelley and Mary on their return (whilst still being prepared to demand that money be sent to him under another name, to avoid scandal). By August 1820 Shelley was in such extreme debt himself, having previously obtained credit on the (false) assumption that he would soon inherit the family estate from his father, that he was finally forced to refuse Godwin’s constant demands for money, writing “I have given you ….the amount of a considerable fortune, & have destituted myself.” Within two years Shelley was dead.

Yet at least in the permanence of the printed word Godwin’s influence on Shelley remains. It is most apparent in Shelley’s political poems, which echo Godwin’s views on the state and his anarchistic vision of society. For instance, in The Masque of Anarchy (1819), which was written as a response to the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, Shelley describes how non-revolutionary, passive resistance can morally defeat tyrants, and how men can become free:

“Then they will return with shame,

To the place from which they came,

And the blood thus shed will speak

In hot blushes on their cheek:

Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many – they are few!”

A tax lawyer by profession and living with a novelist and two cats, Simon Court indulges his passion for history by diving into the Bodleian Library at every opportunity. He has previously written about the English Civil War and has also written a biography of Henry VIII for the ‘History in an Hour’ series. When not immersed in the past he can be found in the here and now, watching Chelsea Football Club.

This post first appeared on the blog of the Wordsworth Trust on 4 October 2015

Works Cited

Hoagwood, Terrence. Skepticism and Ideology: Shelley's Political Prose and its Philosophical Context from Bacon to Marx. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1988. Print

- Mary Shelley

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Anna Mercer

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Byron

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay