Frankenstein at the fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva, review by Anna Mercer

The Frankenstein exhibition at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva provides a journey, in which you first encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which was published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. A new article on this subject is due to appear in the forthcoming issue of the same magazine.

I myself made this visit, twice in fact, and an attest the the extraordinary character of this exhibition. This January I will be introducing an audio-visual component to this space in the form of a series of VLOGs. The inaugural VLOG will focus on the time the Shelley's spent at Diodati and what I believe Diodati stands for. But enough of that, let me turn the podium over to Anna!

In June 2016 I spent five days in Geneva and south east France, travelling in the footsteps of the Shelleys (the details of which – including the Shelleys’ experience, and my own experience, of the Mer de Glace – will be a future blog). On the third day I met Prof. David Spurr from the University of Geneva at the Bodmer Foundation Library and Museum. Spurr had kindly agreed to show us around the current exhibition: Frankenstein: Creation of Darkness, which he curated.

As my partner and I drove across the border from France into Switzerland, and around the beautiful Cologny area of Geneva, we caught a glimpse of Mont Blanc in the distance, a momentous sight; our trip to Chamonix the day before had been so cloudy, rainy and misty that it had seemed as if the mountain was determined to hide from our view. We welcomed the sunshine and we arrived at the Bodmer, which is in a stunning location, and well worth a visit. It opened in 1951, and was initially a research library, but in 2003 an exhibition space was opened, which in itself is an amazing piece of architecture.

Spurr’s tour of the Frankenstein exhibition took us through the manuscripts, books and pictures on show as a story of the text’s history and conception, and all the many literary and artistic influences on Frankenstein, as well as those things which have been influenced by it. The exhibition has (of course) been set up to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the writing of Mary Shelley’s iconic novel. The blurb tells us that the exhibition considers ‘the origins of Frankenstein, the perspectives it opens and the questions it raises.’

The exhibition provides a journey, in which you firstly encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

Cologny, view of Geneva from the Villa Diodati by Jean Dubois, late 19th century / Centre d’iconographie genevoise, Bibliothèque de Genève

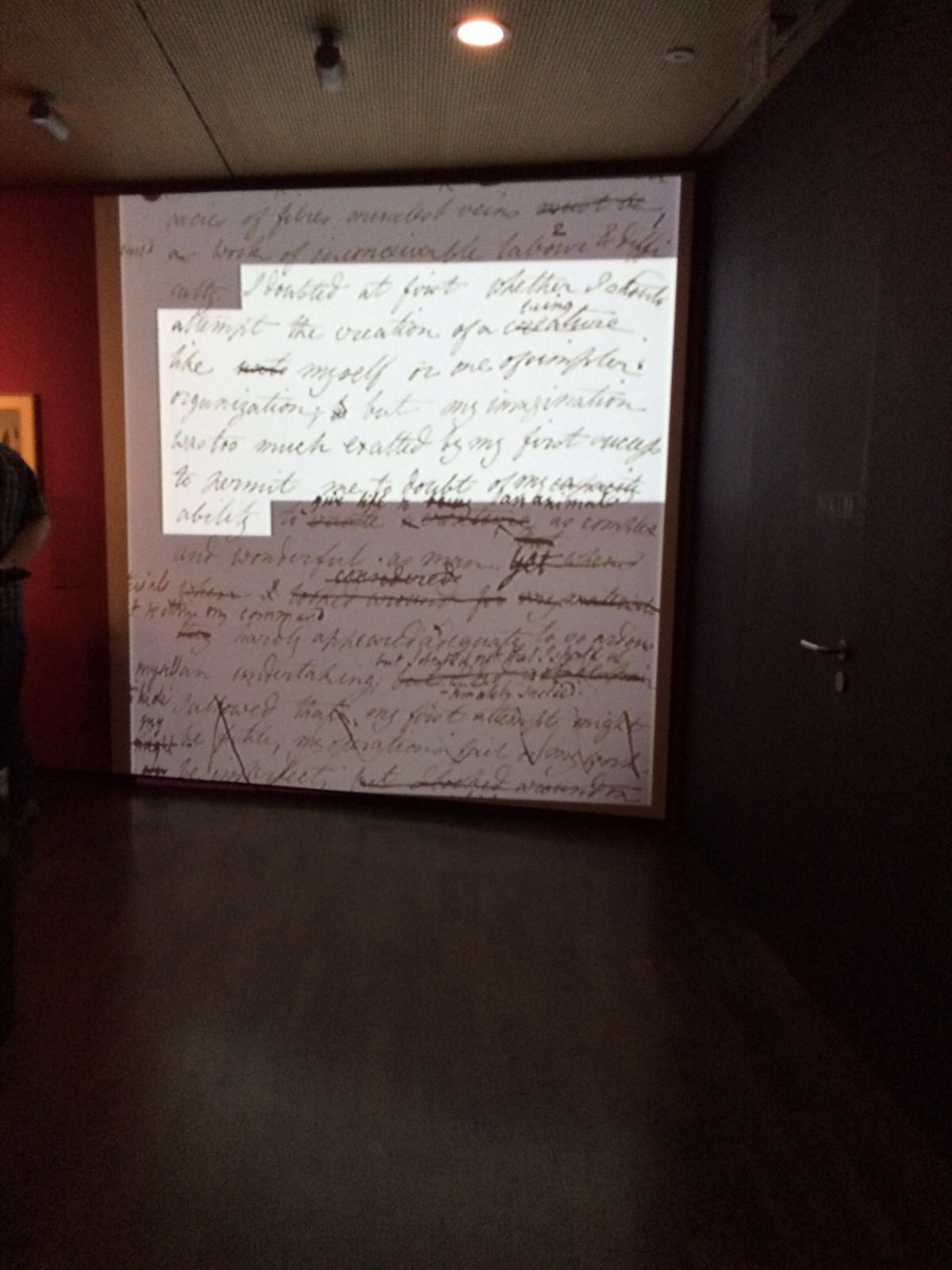

These images are placed on the wall alongside a large glass cabinet holding the treasure of the exhibition: the Frankenstein draft notebooks. The pages on show include the section that would become Vol II, Chapter II of the 1818 Frankenstein where Mary Shelley quotes Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Mutability’. It was exciting to see the original draft of this page, as I often use the manuscript facsimile version in my research. What is fascinating here is that Mary inserts poetry so seamlessly into her dense prose descriptions of Victor’s solitary Alpine travels and fluctuating moods. Moreover, that poetry is composed by her partner Percy Shelley, who then goes over the draft of the novel and makes occasional suggestions to aid her in her task. Within the Frankenstein notebook (which can be also be viewed online at the Shelley-Godwin Archive), you can see how Percy Shelley glosses Mary’s original language, something which is endlessly fascinating.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!-yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost for ever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest. – A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise. – One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!- For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley, ‘Mutability’ (1816). Verses 3 and 4 appear in Frankenstein.

Another particular highlight for me was Mary Shelley’s journal – open on the page which shows her first reference to the composition of Frankenstein – ‘write my story’ (24 July 1816). The bicentenary of this journal entry will be celebrated at an upcoming event I am organising at York and the Keats-Shelley House this month. The choice of which pages to display from these hugely important holographs has been executed wonderfully at the Bodmer exhibition. Mary’s journal has no facsimile (although there is a brilliant print edition, edited by Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert), so to see a volume of it was a powerful reminder that it is a tiny book, heavily worn and containing some of her less decipherable jottings.

The exhibition does not only explore the history of the novel’s author and the scenes that she visited and then used in her text, but also places Frankenstein in a wider literary and socio-political context. As the exhibition explains:

“Mary Shelley’s novel continues to demand attention. The questions it raises remain at the heart of literary and philosophical concerns: the ethics of science, climate change, the technologisation of the human body, the unconscious, human otherness, the plight of the homeless and the dispossessed.”

Some of the exhibits on display are on loan from libraries in the UK, such as the Bodleian and the British Library. Others belong to the Bodmer’s own collection. I was particularly excited to see Mary Shelley’s inscription in the copy of the novel she sent to Lord Byron. This was on sale a while ago at Forbes and eventually went for at least £350,000. She writes: ‘To Lord Byron / from the author’ . Her characteristic modesty is evident here, and to be confronted with this edition reminded me of the complex relationship Mary Shelley actually had with Lord Byron, as she was a major copyist for his works, including The Prison of Chillon and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Canto III. Also on show at the exhibition is the letter from Lord Byron to John Murray explaining that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein (Murray being the publisher who first rejected the work). Frankenstein was published anonymously on January 1, 1818: Byron’s choice to reveal her authorship here is testament to his respect for Mary Shelley as a writer, and his determination to deliver her the credit she deserves.

The signed copy of Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus which went on sale for £350,000. Photo: Peter Harrington

Other literary texts from the period are displayed, including Jane Austen’s Emma (which first appeared in 1816), Polidori’s diary (a subjective record of the infamous events at the Villa Diodati in the summer of 1816), and a copy of Fantasmagoriana (the collection which prompted Byron’s decision to announce a ghost-story competition). Other more idiosyncratic items include the weather report from Geneva in the summer of 1816, showing low temperatures of 7-10 degrees: indeed, it was the year without a summer. Considerable attention is also paid to the relics of Frankenstein as a stage production, including the various castings of the creature.

Spurr gave us fantastic anecdote-enforced fragments of the Shelleys’ history and the story of the exhibition, and then took us along to the Villa Diodati (a 5-minute walk), where we were treated to a stroll round the gardens. The house is privately owned, but beautifully cared for (as we were told) in a way that is in keeping with its momentous history.

It is worth noting just how well the literary texts were placed on display at the exhibition in Geneva, a difficult feat for any curator, as old books are not as blatantly striking as other forms of artwork. This many Shelley texts have not been on display together since Shelley’s Ghost at the Bodleian.

Other non-Shelleyan exhibits include a display of the texts the creature initially reads and learns from: Milton’s Paradise Lost, a volume of Plutach’s Lives, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. Editions of Rousseau remind the visitor that Lord Byron and the Shelleys were also literary tourists when they first travelled to Switzerland in May/June 1816. The exhibition does a superb job in asserting the powerful contribution and legacy these authors created by composing their own works right there, in Geneva, taking their inspirations from the scenes around them. Moreover, it emphasises the creative stimulation provided by the social environment of reading and intellectual discussion at the Villa Diodati.

(Unless mentioned otherwise, all photos are the author’s own).

The Frankenstein exhibition as featured in other articles from the web:

This post first appeared on the blog of the Wordsworth Trust on 3 July 2016 and is reproduced with their kind permission. The original post can be found here

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the British Association for Romantic Studies' the ‘On This Day’ blog. Anna discusses P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ and the inclusion of this poem in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. You can find the original post here.

I think this is an extremely important addition to the Guest Contributors series because it introduces the concept of collaboration. When I was a student in the 1970s and 80s, the idea that Mary had meaningfully collaborated with Shelley* on anything was unheard of. Indeed, the extent of Shelley's involvement in Frankenstein was poorly understood. The modern era has been, however, exceedingly kind to Mary and rather less so for for Shelley. As I have alluded to elsewhere, undergraduates around the world can be forgiven for being literally unaware of a personage by the name Percy Shelley; Mary is all anyone seems to talk about. While on the one hand this may be seen as an much overdue re-balancing of the scales of history, on the other it might be thought of as over-kill. This is where Anna comes in, guiding us through the complicated waters of one of the most interesting literary partnerships in the English language.

I think that today no one should approach the poetry of Shelley without understanding that these two creative people without question influenced one another. This will be a topic for one of my own blogs in the coming months, and I hope Anna will allow me to publish more of her work in this area in the future. Now, an area where Anna and I might disagree would be on the question of whether this poem offers evidence of philosophical idealism. My belief is that even by 1815, Shelley was such a thorough-going philosophical skeptic (in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Drummond) that this is doubtful. This is, however, a quibble, and with that thought, let's turn to one of the modern experts on the subject of Shelleyan collaboration, Anna Mercer.

* A note on my choice of names. For most of the past two centuries, it has been common to refer to Mary Shelley as "Mary" and Percy Shelley as "Shelley". More recently many writers, such as Anna, now refer to them both by their given names. For my part, what matters is that fact that this is the manner in which they invariably referred to one an other; and so I stick with the old ways. I hope this will offend no one.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, from portraits in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!--yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost forever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest.--A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise.--One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!--For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ is an example of his extraordinary poetic talent; in particular these lines show his ability to weave together philosophical ideas and striking imagery within a short section of verse. In this way the poem is reminiscent of Shelley’s famous sonnets such as ‘Ozymandias’ and ‘England in 1819’. However, ‘Mutability’ was written before these other works, which were composed in 1817 and 1819 respectively. The exact date of composition for ‘Mutability’ is not known: the editors of the Longman edition of The Poems of Shelley assign it to ‘winter 1815-16 mainly on grounds of stylistic maturity’. However, the opening lines ‘suggest a late autumn or winter night, but this could have been equally well a night in 1814’.

The ‘On This Day’ blog series thus far has focused on the bicentenaries of events from 1815: if the most likely dating for ‘Mutability’ places its composition in the winter of 1815, the poem must have lingered in the mind of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who would include lines from ‘Mutability’ in Chapter II, Vol II of Frankenstein (1818). Mary Shelley did not begin writing this novel (her first full-length work) until the summer of 1816, which she spent with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John William Polidori in Geneva.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. Mont Blanc and the Glacier des Bossons from above Chamonix, dawn 1836.

It is interesting that we see Percy Shelley’s maturity emerging in ‘Mutability’, as the editors of the Longman Poems of Shelley establish. This maturity can be understood as Shelley’s fine-tuning of his philosophical expressions into a more coherent idealism. The poem’s almost universal application to any ‘man’ who lives on to the ‘morrow’ may be why Mary Shelley chose to place two stanzas (ll.9-16) in her first novel. They appear just before Victor Frankenstein reencounters his creation for the first time since its ‘birth’. He sets off on a precipitous mountain climb to the glaciers of Mont Blanc – alone – in an attempt to combat his anxiety and melancholy state of mind:

The sight of the awful and majestic in nature had indeed always the effect of solemnizing my mind, and causing me to forget the passing cares of life. I determined to go alone, for I was well acquainted with the path, and the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene.

Victor’s view of the valley, the ‘vast mists’, and the rain pouring from the dark sky, prompt him to lament the sensibility of human nature. As in P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’, the narrator considers the inconstancy of the mind. This meditation presents a powerful contradiction that inspires both hope and hopelessness by reminding the reader that a potential for change is always present, whether fortunes be good or bad, whether the individual is positively or negatively affected by his/her surroundings. Either way, all might be completely altered over a short space of time as the human mind responds to external influences. Just as Percy Shelley writes ‘Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; / Nought may endure but Mutability’, Mary Shelley’s protagonist considers how ‘If our impulses were confined to hunger, thirst, and desire, we might be nearly free; but now we are moved by every wind that blows, and a chance word or scene that that word may convey to us’. Lines 9-16 of Shelley’s poem are inserted in the novel after this sentence. Percy Shelley read and edited the draft of Mary’s Frankenstein, and Charles E. Robinson (editor of the Frankenstein manuscripts) has described the possibility of the Shelleys being ‘at work on the Notebooks at the same time, possibly sitting side by side and using the same pen and ink to draft the novel and at the same time to enter corrections’. The inclusion of the lines from ‘Mutability’ could even have been a joint decision.

Sir Walter Scott’s favourable review of Frankenstein from 1818 (when the novel was published anonymously) assumes this poetical insert to be the same authorial voice as its surrounding prose: ‘The following lines […] mark, we think, that the author possesses the same facility in expressing himself in verse as in prose.’ But instead, the implication is that Mary’s prose seamlessly leads into Percy Shelley’s verse, and illustrates the unity of their diction and their collaborative writing arrangement at this time.

A page from Mary Shelley’s journal (1814) showing both Mary and Percy’s hands. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Mary Shelley’s journal shows that the Shelleys read S T Coleridge’s poems in 1815. Lines 5-8 of ‘Mutability’ indicate the possibility of a Coleridgean interest based on STC’s conversation poem ‘The Eolian Harp’. As Coleridge describes ‘the long sequacious notes’ which ‘Over delicious surges sink and rise’, Percy Shelley writes: ‘Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings / Give various response to each varying blast’. The Aeolian Harp or wind-harp (named after Eolus or Aeolus, classical god of the winds) is an image that reoccurs in Romantic poetry and prose. However it is significant that P B Shelley used it in common parlance with Mary, i.e. when writing letters. On 4 November 1814, he writes to her:

I am an harp [sic] responsive to every wind. The scented gale of summer can wake it to sweet melody, but rough cold blasts draw forth discordances & jarring sounds.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works. Beyond the Frankenstein notebooks, there are even instances of the Shelleys altering and/or influencing each other’s compositions in a reciprocal literary dialogue (something my work as a PhD candidate at the University of York is seeking to identify and explore in depth). If ‘Mutability’ was written in winter 1815 (or even earlier), maybe Mary Shelley looked over it, and kept it in mind in relation to her own creative writing – and therefore the poem found its way into her first novel. These details suggest that the Shelleys’ literary relationship was blossoming in the winter of 1815 (exactly 200 years ago), prior to their most significant collaboration on Frankenstein in 1816-1818.

References:

S. T. Coleridge, The Complete Poems ed. by William Keach (London: Penguin, 1997 repr. 2004) p. 87, 464.

Charles E. Robinson (ed.), ‘Introduction’ in Mary Shelley, The Frankenstein Notebooks Vol I (London: Garland, 1996), p. lxx.

Sir Walter Scott, ‘Remarks on Frankenstein’ in Mary Shelley: Bloom’s Classic Critical Views (New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008) p. 93.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: A Norton Critical Edition ed. by J. Paul Hunter (London: 1996 repr. 2012) pp. 65-67.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Mutability’ in The Poems of Shelley Vol I ed. by Geoffrey Matthews and Kelvin Everest (London: Longman, 1989) pp. 456-7.

- Mary Shelley

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Anna Mercer

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Byron

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay