In the Footsteps of Mary and Percy Shelley. By Anna Mercer

One of the great things about studying Shelley is where it can take you if you are intrepid. In the course of his short life he traveled to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Devon, France, Switzerland and Italy - and some of the places he visited are among the most sublime and picturesque in Europe. Join Anna Mercer for a trip to Shelley's Mont Blanc!

My Guest Contributor series continues with another travel feature by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in completing her thesis as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which was published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. A new article on this subject is due to appear in the forthcoming issue of the same magazine.

One of the great things about studying Shelley is where it can take you if you are intrepid. In the course of his short life he traveled to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Devon, France, Switzerland and Italy - and some of the places he visited are among the most sublime and picturesque in Europe. I have an important trip planned to Lerici in Italy where he died and have both written and audio-visual material planned for publication in May.

In the meantime enjoy Anna's record of her visit to Geneva and Chamonix. I myself made this trip and I can tell you it is absolutely stunning at any time of the year. You can watch my VLOG about my visit to the Villa Diodati here.

In June 2016 I made a pilgrimage to an area in Europe known for its sublime scenery. I have read so much about the snowy peaks of the Alps and the shores of Lake Geneva, primarily from two sources that figure in my life because of my PhD research at the University of York. I am studying Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, two Romantic authors who, before their marriage but after their romantic union, spent the summer in the environs of Geneva and Chamonix in 1816, exactly 200 years before I arrived there.

Percy Shelley had originally thought of leaving England for Italy. The Shelleys were instead convinced to head to Cologny near Geneva by their travellng companion Claire Clairmont, Mary’s step-sister, who in London had begun an affair with Lord Byron.

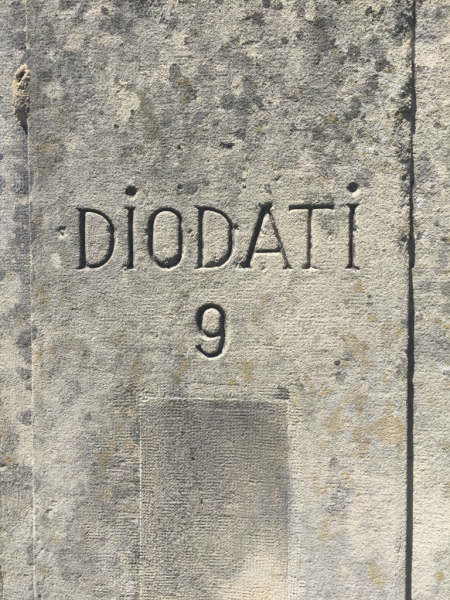

On 13 May 1816 the Shelleys and Claire arrived in Geneva, followed on 25 May by Byron and his physician Dr. John Polidori. By June, both parties had taken residences close to each other on the shores of the lake; Byron stayed at the Villa Diodati. Incessant rain often prevented them from going out on the water in the evenings, and even stopped Percy, Mary and Claire from returning to their own lodgings.[1] The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 has devastated the weather across Europe, and 1816 is recalled now as ‘the year without a summer’.

I also arrived to an atmospherically rainy Geneva:

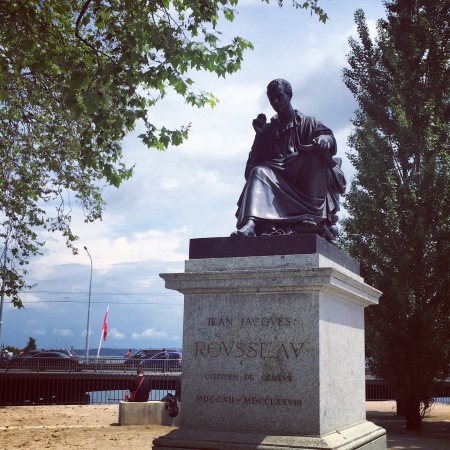

The weather eventually cleared, and we explored the town. Like the Shelleys, we were intrigued by the literary greats who had graced the city, among the Rousseau.

During the 1816 summer, Percy, Mary and Claire stayed at Maison Chapuis but often spent time at Byron’s grander lodgings nearby. Geneva is where Mary Shelley began writing her most famous and enduring novel, Frankenstein (first published in 1818). Mary’s terrifying novel – according to her 1831 introduction – was ostensibly inspired by a ‘waking dream’ she had after hearing Percy and Byron’s discussions on ‘the nature of the principle of life’ to which she ‘was a devout but nearly silent listener’. This account of her literary genius is characteristically modest, as her silence is in all likelihood overplayed; the community at Geneva in 1816 offered a stimulating intellectual environment and Percy and Mary collaborated on the novel as well as many other works.

Mary began writing Frankenstein in June 1816. The Shelleys met Byron on 27 May, and he took up residence at Diodati on 10 June, and by June 22 Percy Shelley and Byron went on a tour of Lake Geneva together. So, although Mary only recorded the composition of Frankenstein in her journal in July, it is likely the novel was started between 10-22 June.[2]

In a previous post here at www.grahamhenderson.ca, I reviewed the excellent exhibition on Frankenstein at the Bodmer Foundation Library and Museum: Frankenstein: Creation of Darkness. We were treated with a walk around the grounds of the Villa Diodati itself.

Percy and Mary included descriptions of their travels in the 1817 publication History of a Six Weeks’ Tour. Mary’s view of Geneva was muted to say the least:

There is nothing […] in it that can repay you for the trouble of walking over its rough stones. The houses are high, the streets narrow, many of them on the ascent, and no public building of any beauty to attract your eye, or any architecture to gratify your taste. The town is surrounded by a wall, the three gates of which are shut exactly at ten o’clock, when no bribery (as in France) can open them (101-2).

However, the dramatic weather offered her respite:

The lake is at our feet, and a little harbour contains our boat, in which we still enjoy our evening excursions on the water. Unfortunately we do not now enjoy those brilliant skies that hailed us on our first arrival to this country. An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house; but when the sun bursts forth it is with a splendour and heat unknown in England. The thunder storms that visit us are grander and more terrific than I have ever seen before. We watch them as they approach from the opposite side of the lake, observing the lightning play among the clouds in various parts of the heavens, and dart in jagged figures upon the piny heights of Jura, dark with the shadow of the overhanging cloud, while perhaps the sun is shining cheerily upon us. One night we enjoyed a finer storm than I had ever before beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads amid the darkness (99-100).

I am particularly fascinated by this jointly-authored publication History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, Mary’s first foray into print (besides her early light verses published in her father’s library). The text of this volume is an intermingling of voices, the provenance of each section being drawn from a joint journal, numerous letters and original words composed for the edition. I will be discussing the History in a paper at the British Association for Romantic Studies conference in York in July, 2017.

On our first day in Geneva, after wandering around and dodging the rain, we immediately set off to cross the border. We were staying in an idyllic, isolated chalet in France, and the first place we wanted to visit the next day was the site of many inspirations for both Percy and Mary: the town of Chamonix, which rests under the imposing gaze of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak.

Our travels from Geneva to the French Alps reminded me of Mary Shelley’s third novel, The Last Man (1826), in which the protagonist Lionel and his companion Adrian (a Percy Shelley-esque figure) make a similar trajectory:

We left the fair margin of the beauteous lake of Geneva, and entered the Alpine ravines; tracing to its source the brawling Arve, through the rock-bound valley of Servox, beside the mighty waterfalls, and under the shadow of the inaccessible mountains, we travelled on; while the luxuriant walnut-tree gave place to the dark pine, whose musical branches swung in the wind, and whose upright forms had braved a thousand storms – till the verdant sod, the flowery dell, and shrubbery hill were exchanged for the sky-piercing, untrodden, seedless rock, “the bones of the world, waiting to be clothed with every thing necessary to give life and beauty”** Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Norway.

This excerpt concludes with a quotation taken from Mary Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft. Her Letters written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark inspired Mary in her own travel writing. This was a text in which the author sought ‘to let my remarks and reflections flow unrestrained’ (Advertisement). The writing of Mary Shelley’s radical parents (her father was William Godwin) were some of the texts the Shelleys were both reading – occasionally aloud together – in 1814, the year of their elopement, and their first journey to the continent. Texts included Letters written during a Short Residence by Wollstonecraft and Caleb Williams by Godwin.[3]

On the day of our arrival in Chamonix, the mountains were not only seemingly inaccessible, but invisible. Low cloud prevented us from identifying Mont Blanc above us, but did not damage the charming nature of the town, now a popular ski-resort, and the drive into the Valley was still dramatic:

Despite the cloud, we decided to get the train to the ‘Mer de Glace’. Perhaps bad weather would have prevented tourists from making the journey in the Shelleys’ day, but in 2016 the Montenvers Railway (opened 1909) takes you right up to the viewing platform.

On arrival, we were sorely disappointed, as we couldn’t see a thing. Mildly upset that we had traveled all this way up and wouldn’t see the glacier itself, my companion convinced me to take the cable car that descends into the mist despite the slightly miserable conditions.

When we landed at the bottom, the glacier was in full view. I will firstly give you Percy Shelley’s description of this natural wonder:

We have returned from visiting the glacier of Montanvert, or as it is called, the Sea of Ice, a scene in truth of dizzying wonder. The path that winds to it along the side of a mountain, now clothed with pines, now intersected with snowy hollows, is wide and steep. […] We arrived at Montanvert, […] On all sides precipitous mountains, the abodes of unrelenting frost, surround this vale: their sides are banked up with ice and snow, broken, heaped high, and exhibiting terrific chasms. The summits are sharp and naked pinnacles, whose overhanging steepness will not even permit snow to rest upon them. Lines of dazzling ice occupy here and there their perpendicular rifts, and shine through the driving vapours with inexpressible brilliance; they pierce the clouds like things not belonging to this earth. The vale itself is filled with a mass of undulating ice, and has an ascent sufficiently gradual even to the remotest abysses of these horrible desarts. It is only half a league (about two miles) in breadth, and seems much less. It exhibits an appearance as if frost had suddenly bound up the waves and whirlpools of a mighty torrent. We walked some distance upon its surface. The waves are elevated about 12 or 15 feet from the surface of the mass, which is intersected by long gaps of unfathomable depth, the ice of whose sides is more beautifully azure than the sky. In these regions every thing changes, and is in motion. This vast mass of ice has one general progress, which ceases neither day nor night; it breaks and bursts for ever: some undulations sink while others rise; it is never the same. The echo of rocks, or of the ice and snow which fall from their overhanging precipices, or roll from their aerial summits, scarcely ceases for one moment. One would think that Mont Blanc, like the god of the Stoics, was a vast animal, and that the frozen blood for ever circulated through his stony veins.We dined (M***, C***, and I) on the grass, in the open air, surrounded by this scene. The air is piercing and clear. We returned down the mountain, sometimes encompassed by the driving vapours, sometimes cheered by the sunbeams, and arrived at our inn by seven o’clock (History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, 164-168).

However, we were not just relieved to be able to see more than cloud, but shocked by the lack of glacier before us.

Carl Hackert, ‘Vue de la Mer de Glace et de l’Hôpital de Blair’ (1781) (Centre d’iconographie genevois).

Percy Shelley’s premonition that Buffon’s ‘sublime but gloomy theory’ that ‘this globe which we inhabit will at some future period be changed into a mass of frost’ (161-2), was entirely unfounded. We knew that the ice was melting – the majority of us do (I am avoiding any political comment here) – but we were still affected by this huge difference across the decades. You can read more on this subject at the British Romantic Writing and Environmental Catastrophe website, an AHRC-funded project at the University of Leeds.

You can now go inside the glacier itself:

When we went back up in the cable car, the clouds had cleared and we had an astounding view of the Mer de Glace and surrounding peaks. This reminded me of Volume II, Chapter II of Frankenstein, as Victor makes the same ascent. He makes it alone, because ‘the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene’. Just as in our visit, in the novel the clouds clear from the protagonist around midday:

It was nearly noon when I arrived at the top of the ascent. For some time I sat upon the rock that overlooks the sea of ice. A mist covered both that and the surrounding mountains. Presently a breeze dissipated the cloud, and I descended upon the glacier.From the side where I now stood Montanvert was exactly opposite, at the distance of a league; and above it rose Mont Blanc, in awful majesty. I remained in a recess of the rock, gazing on this wonderful and stupendous scene. The sea, or rather the vast river of ice, wound among its dependent mountains, whose aerial summits hung over its recesses. Their icy and glittering peaks shone in the sunlight over the clouds. My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy.

On our way back to Chamonix, we had the same luck again – an overwhelming sight.

We returned two days later in marginally better weather to take the cable-car that made the ascent of Mont Blanc itself. To be honest, the cloud had left me confused as to where the peak of this infamous mountain was.

A ride up the side of the mountain to the Aiguille Du Midi took my breath away. This trip is a must for any visitor to the area. We were warned that the visibility would be bad at the top, but when we arrived the clouds cleared and left us with spectacular views. If you are a lover of the Shelleys, you will be further mystified in wondering just what those two incredible authors would have made of the sight, if they could have ascended to 3,842m and see the ‘vast animal’ Mont Blanc this close.

Mont Blanc appears in both of the Shelleys’ works (such as Mary’s Frankenstein and The Last Man), but it is Percy Shelley’s poem dedicated to the mountain that reveals the full extent of their awe. You can read the full poem here, but I will leave you with its final lines:

Mont Blanc yet gleams on high:—the power is there,

The still and solemn power of many sights,

And many sounds, and much of life and death.

In the calm darkness of the moonless nights,

In the lone glare of day, the snows descend

Upon that Mountain; none beholds them there,

Nor when the flakes burn in the sinking sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them:— Winds contend

Silently there, and heap the snow with breath

Rapid and strong, but silently! Its home

The voiceless lightning in these solitudes

Keeps innocently, and like vapour broods

Over the snow. The secret strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome

Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!

And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,

If to the human mind’s imaginings

Silence and solitude were vacancy?

This article is reprinted with the kind permission of the author. It originally appeared 6 February 2017 on her excellent blog which you can find here.

[1] All details from MWS Journals, 103-108. Nb. No journal by Mary (lost) from 13 May 1815 – 21 July 1816.

[2] ‘The impression given by these accounts [Mary Shelley’s intro, PBS’s preface and Thomas Moore] is of a leisurely time-scheme, yet it must in fact have been fairly brief: Byron met Shelley’s party at Sécheron on 27 May, and did not move to the Villa Diodati until 10 June; the journey round Lake Leman began on 22 June, and the novel must have been started between these last two dates’. M. K. Joseph ‘The Composition of Frankenstein’ in Frankenstein ed. J. Paul Hunter (London: Norton, 1996 repr. 2012), 171.

[3] MWS, Journals, 22, 26, 649-50, 684.

Frankenstein at the fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva, review by Anna Mercer

The Frankenstein exhibition at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva provides a journey, in which you first encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which was published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. A new article on this subject is due to appear in the forthcoming issue of the same magazine.

I myself made this visit, twice in fact, and an attest the the extraordinary character of this exhibition. This January I will be introducing an audio-visual component to this space in the form of a series of VLOGs. The inaugural VLOG will focus on the time the Shelley's spent at Diodati and what I believe Diodati stands for. But enough of that, let me turn the podium over to Anna!

In June 2016 I spent five days in Geneva and south east France, travelling in the footsteps of the Shelleys (the details of which – including the Shelleys’ experience, and my own experience, of the Mer de Glace – will be a future blog). On the third day I met Prof. David Spurr from the University of Geneva at the Bodmer Foundation Library and Museum. Spurr had kindly agreed to show us around the current exhibition: Frankenstein: Creation of Darkness, which he curated.

As my partner and I drove across the border from France into Switzerland, and around the beautiful Cologny area of Geneva, we caught a glimpse of Mont Blanc in the distance, a momentous sight; our trip to Chamonix the day before had been so cloudy, rainy and misty that it had seemed as if the mountain was determined to hide from our view. We welcomed the sunshine and we arrived at the Bodmer, which is in a stunning location, and well worth a visit. It opened in 1951, and was initially a research library, but in 2003 an exhibition space was opened, which in itself is an amazing piece of architecture.

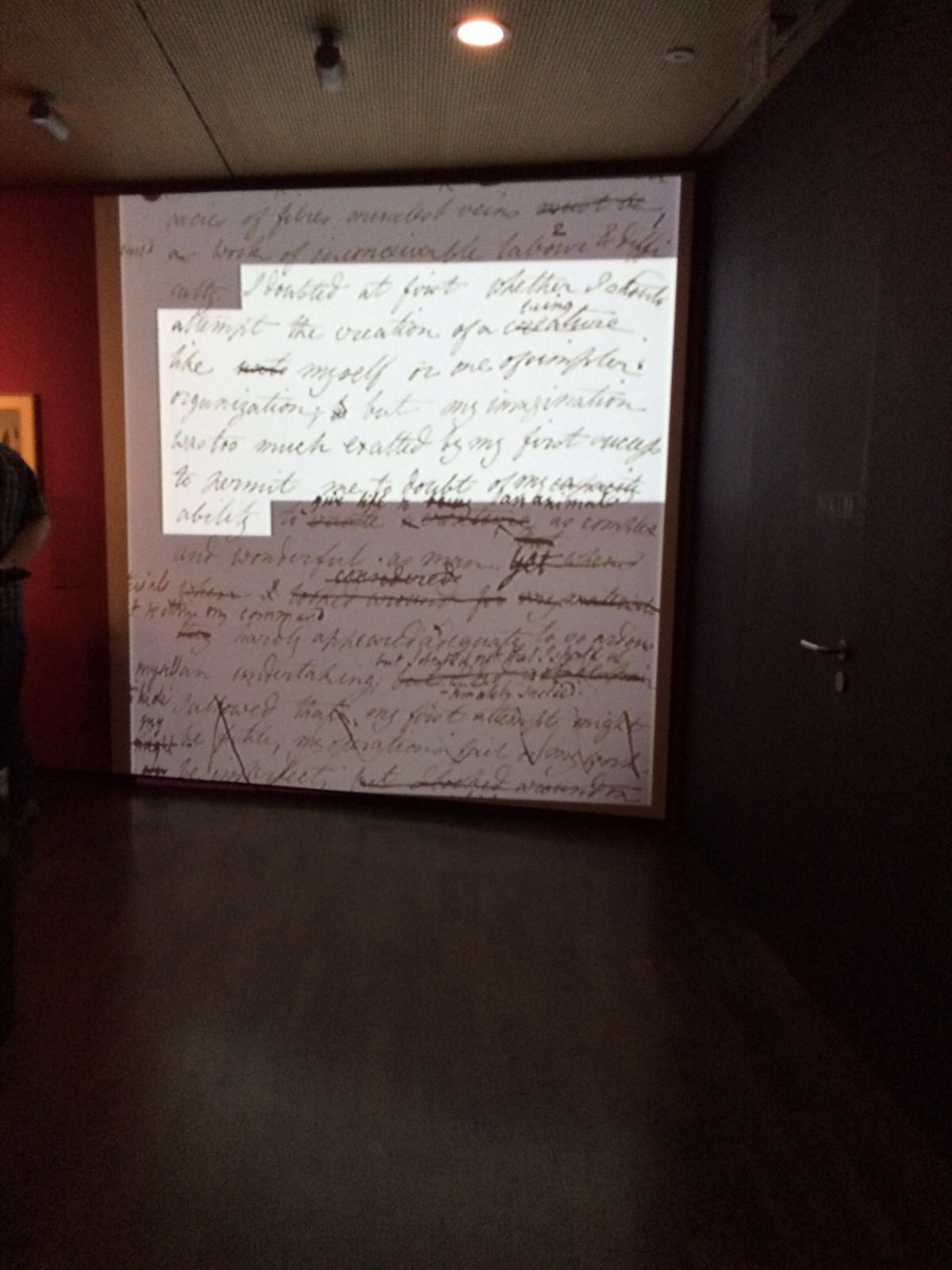

Spurr’s tour of the Frankenstein exhibition took us through the manuscripts, books and pictures on show as a story of the text’s history and conception, and all the many literary and artistic influences on Frankenstein, as well as those things which have been influenced by it. The exhibition has (of course) been set up to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the writing of Mary Shelley’s iconic novel. The blurb tells us that the exhibition considers ‘the origins of Frankenstein, the perspectives it opens and the questions it raises.’

The exhibition provides a journey, in which you firstly encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

Cologny, view of Geneva from the Villa Diodati by Jean Dubois, late 19th century / Centre d’iconographie genevoise, Bibliothèque de Genève

These images are placed on the wall alongside a large glass cabinet holding the treasure of the exhibition: the Frankenstein draft notebooks. The pages on show include the section that would become Vol II, Chapter II of the 1818 Frankenstein where Mary Shelley quotes Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Mutability’. It was exciting to see the original draft of this page, as I often use the manuscript facsimile version in my research. What is fascinating here is that Mary inserts poetry so seamlessly into her dense prose descriptions of Victor’s solitary Alpine travels and fluctuating moods. Moreover, that poetry is composed by her partner Percy Shelley, who then goes over the draft of the novel and makes occasional suggestions to aid her in her task. Within the Frankenstein notebook (which can be also be viewed online at the Shelley-Godwin Archive), you can see how Percy Shelley glosses Mary’s original language, something which is endlessly fascinating.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!-yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost for ever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest. – A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise. – One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!- For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley, ‘Mutability’ (1816). Verses 3 and 4 appear in Frankenstein.

Another particular highlight for me was Mary Shelley’s journal – open on the page which shows her first reference to the composition of Frankenstein – ‘write my story’ (24 July 1816). The bicentenary of this journal entry will be celebrated at an upcoming event I am organising at York and the Keats-Shelley House this month. The choice of which pages to display from these hugely important holographs has been executed wonderfully at the Bodmer exhibition. Mary’s journal has no facsimile (although there is a brilliant print edition, edited by Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert), so to see a volume of it was a powerful reminder that it is a tiny book, heavily worn and containing some of her less decipherable jottings.

The exhibition does not only explore the history of the novel’s author and the scenes that she visited and then used in her text, but also places Frankenstein in a wider literary and socio-political context. As the exhibition explains:

“Mary Shelley’s novel continues to demand attention. The questions it raises remain at the heart of literary and philosophical concerns: the ethics of science, climate change, the technologisation of the human body, the unconscious, human otherness, the plight of the homeless and the dispossessed.”

Some of the exhibits on display are on loan from libraries in the UK, such as the Bodleian and the British Library. Others belong to the Bodmer’s own collection. I was particularly excited to see Mary Shelley’s inscription in the copy of the novel she sent to Lord Byron. This was on sale a while ago at Forbes and eventually went for at least £350,000. She writes: ‘To Lord Byron / from the author’ . Her characteristic modesty is evident here, and to be confronted with this edition reminded me of the complex relationship Mary Shelley actually had with Lord Byron, as she was a major copyist for his works, including The Prison of Chillon and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Canto III. Also on show at the exhibition is the letter from Lord Byron to John Murray explaining that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein (Murray being the publisher who first rejected the work). Frankenstein was published anonymously on January 1, 1818: Byron’s choice to reveal her authorship here is testament to his respect for Mary Shelley as a writer, and his determination to deliver her the credit she deserves.

The signed copy of Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus which went on sale for £350,000. Photo: Peter Harrington

Other literary texts from the period are displayed, including Jane Austen’s Emma (which first appeared in 1816), Polidori’s diary (a subjective record of the infamous events at the Villa Diodati in the summer of 1816), and a copy of Fantasmagoriana (the collection which prompted Byron’s decision to announce a ghost-story competition). Other more idiosyncratic items include the weather report from Geneva in the summer of 1816, showing low temperatures of 7-10 degrees: indeed, it was the year without a summer. Considerable attention is also paid to the relics of Frankenstein as a stage production, including the various castings of the creature.

Spurr gave us fantastic anecdote-enforced fragments of the Shelleys’ history and the story of the exhibition, and then took us along to the Villa Diodati (a 5-minute walk), where we were treated to a stroll round the gardens. The house is privately owned, but beautifully cared for (as we were told) in a way that is in keeping with its momentous history.

It is worth noting just how well the literary texts were placed on display at the exhibition in Geneva, a difficult feat for any curator, as old books are not as blatantly striking as other forms of artwork. This many Shelley texts have not been on display together since Shelley’s Ghost at the Bodleian.

Other non-Shelleyan exhibits include a display of the texts the creature initially reads and learns from: Milton’s Paradise Lost, a volume of Plutach’s Lives, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. Editions of Rousseau remind the visitor that Lord Byron and the Shelleys were also literary tourists when they first travelled to Switzerland in May/June 1816. The exhibition does a superb job in asserting the powerful contribution and legacy these authors created by composing their own works right there, in Geneva, taking their inspirations from the scenes around them. Moreover, it emphasises the creative stimulation provided by the social environment of reading and intellectual discussion at the Villa Diodati.

(Unless mentioned otherwise, all photos are the author’s own).

The Frankenstein exhibition as featured in other articles from the web:

This post first appeared on the blog of the Wordsworth Trust on 3 July 2016 and is reproduced with their kind permission. The original post can be found here

- Mary Shelley

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Anna Mercer

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Byron

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay