The Peterloo Massacre and Percy Shelley by Paul Bond

Paul Bond’s essay is nothing less than a tour de force encapsulating and documenting Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his own era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand his radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond.

In the early autumn, my online “Shelley Alert” trip wire came alive with a link to an article published by Paul Bond on the World Socialist Web Site (“WSWS”) under the auspices of the International Committee of the Fourth International (“ICFI”). Paul, it turns out, is an active member of the Trotskyist movement and has been writing for the WSWS since its launch in 1998. It also turns out he is an ardent admirer of Percy Shelley. That someone like Paul would be interested in Shelley and that the ICFI would publish his article about Shelley did not surprise me in the least. Though I suspect it might arouse the curiosity of a goodly portion of Shelley’s current fan base.

Before we delve further into this, let’s find out exactly what the WSWS is? Understanding this may explain a lot:

The World Socialist Web Site is published by the International Committee of the Fourth International, the leadership of the world socialist movement, the Fourth International founded by Leon Trotsky in 1938.

The WSWS aims to meet the need, felt widely today, for an intelligent appraisal of the problems of contemporary society. It addresses itself to the masses of people who are dissatisfied with the present state of social life, as well as its cynical and reactionary treatment by the establishment media.

Our web site provides a source of political perspective to those troubled by the monstrous level of social inequality, which has produced an ever-widening chasm between the wealthy few and the mass of the world's people. As great events, from financial crises to eruptions of militarism and war, break up the present state of class relations, the WSWS will provide a political orientation for the growing ranks of working people thrown into struggle.

We anticipate enormous battles in every country against unemployment, low wages, austerity policies and violations of democratic rights. The World Socialist Web Site insists, however, that the success of these struggles is inseparable from the growth in the influence of a socialist political movement guided by a Marxist world outlook.

The standpoint of this web site is one of revolutionary opposition to the capitalist market system. Its aim is the establishment of world socialism. It maintains that the vehicle for this transformation is the international working class, and that in the twenty-first century the fate of working people, and ultimately mankind as a whole, depends upon the success of the socialist revolution.

You can learn more about them here.

For those of you familiar with the radical Percy Shelley, this will, of course, make sense. Shelley has been an inspiration to those on the left from the early 1800s. I have written extensively about this in my articles “My Father’s Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys”, “Percy Bysshe Shelley in Our Time” and “Jeremy Corbin is Right: Poetry Can Change the World”.

I think the fact that the WSWS has published an extensive article exploring Shelley’s radicalism is an important and salutary moment. It should help to reconnect Shelley to a new generation of radicals. The principal reason that Shelley remains relevant today is almost exclusively connected to his radicalism. His love poetry is exquisite and reminds us that PB was a three dimensional person. But there is an enormous amount of brilliant love poetry out there; and precious little radical poetry - having said that a great deal of Shelley’s love poetry is in fact a very radical variant of love poetry.

But it is Shelley’s radicalism that makes him stand out as a giant among his contemporaries. Little wonder then that Eleanor Marx proudly declaimed in a famous speech in 1888: “We claim his as a socialist.” Shelley’s radicalism inspired generations of activists and radicals; radicals who, explicitly inspired by Shelley, went on to change the world for the better. Is there a better example of this than the effect Shelley had on Pauline Newman, one of the founders of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union? You can read more about this in my article “The Story of the Mask of Anarchy: From Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire”. And please read Michael Demson’s brilliant graphic novel of the same name. Links to buy it are in my article.

Two of the best biographies of Shelley were written by life-long members of the left. The first, Kenneth Neill Cameron (an avowed Marxist), penned The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical. The other, Paul Foot (the greatest crusading journalist of his generation), authored The Red Shelley. You can read Paul Foot’s spellbinding address to the 1981 International Marxism Conference in London here. It took me over two hundred hours to transcribe and properly footnote his speech!

For both Engels and Marx, Shelley was an inspiration:

Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

Marx:

The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of Socialism.

Eleanor Marx supplied the principle reason for these assessments of Shelley. She wrote,

More than anything else that makes us claim Shelley as a Socialist is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery.

This grim portrayal of the tyranny faced by the citizens of Shelley’s and Marx’s eras has an equally grim, modern resonance. One need to look no further than Marxist-inspired writers such as Astra Taylor (The People’s Platform) and Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) to come to grips with the fact that the situation has, if anything, got worse. Our modern “possessing class” of digital overlords threaten not simply to strip the people of their labour, but to turn our very lives into the raw materials that feed the rapacious, insatiable demands their modern “surveillance capitalism”.

However, let me turn the floor over to Paul Bond whose essay is something of a tour de force that encapsulates Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand this radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond. You can follow Paul on Twitter @paulbondwsws and the World Socialist Web Site @WSWS_Updates.

The caption photo at top is of Eleanor Marx (middle) with her two sisters - Jenny Longuet, Laura Marx, father Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Eleanor was a champion of PBS.

The Peterloo Massacre and Shelley

by Paul Bond

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, a critical event in British history. On August 16, 1819, a crowd of 60,000 to 100,000 protestors gathered peacefully on Manchester’s St. Peter’s Field. They came to appeal for adult suffrage and the reform of parliamentary representation.The disenfranchised working class—cotton workers, many of them women, with a large contingent of Irish workers—who made up the crowd were struggling with the increasingly dire economic conditions following the end of the Napoleonic Wars four years earlier.

Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest the speakers and sent cavalry of Yeomanry and a regular army regiment to attack the crowd. They charged with sabres drawn. Eighteen people were killed and up to 700 injured.

On August 16 of this year the WSWS published an appraisal of the massacre.

The Peterloo Massacre elicited an immediate and furious response from the working class and sections of middle-class radicals.

The escalation of repression by the ruling class that followed, resulting in a greater suppression of civil liberties, was met with meetings of thousands and the widespread circulation of accounts of the massacre. There was a determination to learn from the massacre and not allow it to be forgotten or misrepresented. Poetic responses played an important part in memorialising Peterloo.

Violent class conflict erupted across north western England. Yeomen and hussars continued attacks on workers across Manchester, and the ruling class launched an intensive campaign of disinformation and retribution.

At the trial of Rochdale workers charged with rioting on the night after Peterloo, Attorney General Sir Robert Gifford made clear that the ruling class would stop at nothing to crush the development of radical and revolutionary sentiment in the masses. He declared: “Men deluded themselves if they thought their condition would be bettered by such kind of Reform as Universal Suffrage, Annual Parliaments, and Vote by Ballot; or that it was just that the property of the country ought to be equally divided among its inhabitants, or that such a daring innovation would ever take place.”

Samuel Bamford (1788–1872), 'The Radical', Silk Weaver of Middleton by Charles Potter

Samuel Bamford, a reformer and weaver who led a contingent of several thousand marchers to Manchester from the town of Middleton, said he spent the evening of the massacre “brooding over a spirit of vengeance towards the authors of our humiliation.” Bamford told the judge at his trial for sedition that he would not recommend non-violent protest again.

Workers took a more direct response, even as the military were being deployed widely against the population. Despite the military presence, and press claims that the city had been subdued, riots continued across Manchester.

Two women were shot by hussars on August 20. A fortnight after Peterloo, the most affected area, Manchester’s New Cross district, was described in the London press as a by-word for trouble and a risky area for the wealthy to pass through. Soldiers were shooting in the area to disperse rioters. On August 18, a special constable fired a loaded pistol in the New Cross streets and was attacked by an angry crowd, who beat him to death with a poker and stoned him.

There was a similar response elsewhere locally, with riots in Oldham and Rochdale and what has been described by one historian as “a pitched battle” in Macclesfield on the night of August 17.

Crowds in their thousands welcomed the coach carrying Henry Hunt and the other arrested Peterloo speakers to court in Salford, the city across the River Irwell from Manchester. Salford’s magistrates reportedly feared a “tendency to tumult,” while in Bolton the Hussars had trouble keeping the public from other prisoners. The crowd shouted, “Down with the tyrants!”

While the courts meted out sharper punishment to the arrested rioters, mass meetings and protests continued across Britain. Meetings to condemn the massacre took place in Wakefield, Glasgow, Sheffield, Huddersfield and Nottingham. In Leeds, the crowd was asked if they would support physical force to achieve radical reform. They unanimously raised their hands.

These were meetings attended by tens of thousands and they did not end despite the escalating repression. The Twitter account Peterloo 1819 News (@Live1819) is providing a useful daily update on historical responses until the end of this year.

A protest meeting at London’s Smithfield on August 25 drew crowds estimated at 15,000-40,000. At least 20,000 demonstrated in Newcastle on October 11. The mayor wrote dishonestly to the home secretary, Lord Sidmouth, of this teetotal and entirely orderly peaceful demonstration that 700 of the participants “were prepared with arms (concealed) to resist the civil power.”

The response was felt across the whole of the British Isles. In Belfast, the Irishman newspaper wrote, “The spirit of Reform rises from the blood of the Manchester Martyrs with a giant strength!”

A meeting of 10,000 was held in Dundee in November that collected funds “for obtaining justice for the Manchester sufferers.” That same month saw a meeting of 10,000 in Leicester and one of 12,000 near Burnley. In Wigan, just a few miles north of the site of Peterloo, around 20,000 assembled to discuss “parliamentary reform and the massacre at Manchester.” The yeomanry were standing ready at many of these meetings.

The state was determined to suppress criticism. Commenting on the events, it published false statements about the massacre and individual deaths. Radical MP Sir Francis Burdett was fined £2,000 and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for “seditious libel” in response to his denunciation of the Peterloo massacre. On September 2, he addressed 30,000 at a meeting in London’s Palace Yard, demanding the prosecution of the Manchester magistrates.

Richard Carlile

Radical publisher Richard Carlile, who had been at Peterloo, was arrested late in August. He was told that proceedings against him would be dropped if he stopped circulating his accounts of the massacre. He did not and was subsequently tried and convicted of seditious libel and blasphemy.

The main indictment against him was his publication of Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. Like Bamford, Carlile also concluded that armed defence was now necessary: He wrote, “Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform should never go unarmed—retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.”

In Chudleigh, Devon, John Jenkins was arrested for owning a crude but accurate print of the yeomanry charging the Peterloo crowd when Henry Hunt was arrested. A local vicar, a magistrate, informed on Jenkins, whose major “crime” was that he was sharing information about Peterloo. Jenkins was showing the print to people, using a magnifying glass in a viewing box. The charge against Jenkins argued that the print was “intended to inflame the minds of His Majesty’s Subjects and to bring His Majesty’s Soldiery into hatred and contempt.”

Against this attempt to suppress the historical record there was a wide range of efforts to preserve the memory of Peterloo. Verses, poems and songs appeared widely. In October, a banner in Halifax bore the lines:

With heartfelt grief we mourn for thoseWho fell a victim to our causeWhile we with indignation viewThe bloody field of Peterloo.

Anonymous verses were published on cheap broadsides, while others were credited to local radical workers. Many recounted the day’s events, often with a subversive undercurrent. The broadside ballad, “A New Song on the Peterloo Meeting,” for example, was written to the tune “Parker’s Widow,” a song about the widow of 1797 naval mutineer Richard Parker.

Weaver poet John Stafford, who regularly sang at radical meetings, wrote a longer, more detailed account of the day’s events in a song titled “Peterloo.”

The shoemaker poet Allen Davenport satirised in song the Reverend Charles Wicksteed Ethelston of Cheetham Hill—a magistrate who had organised spies against the radical movement and, as the leader of the Manchester magistrates who authorised the massacre, claimed to have read the Riot Act at Peterloo.

Ethelston played a vital role in the repression by the authorities after Peterloo. At a September hearing of two men who were accused of military drilling on a moor in the north of Manchester the day before Peterloo, he told one of them, James Kaye, “I believe that you are a downright blackguard reformer. Some of you reformers ought to be hanged; and some of you are sure to be hanged—the rope is already round your necks; the law has been a great deal too lenient with you.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Clint (after Amelia Curran) c. 1829

Ethelston was also attacked in verse by Bamford, who called him “the Plotting Parson.” Davenport’s “St. Ethelstone’s Day” portrays Peterloo as Ethelston‘s attempt at self-sanctification. Its content is pointed— “In every direction they slaughtered away, Drunken with blood on St. Ethelstone’s Day”—but Davenport sharpens the satire even further by specifying the tune “Gee Ho Dobbin,” the prince regent’s favourite. (These songs are included on the recent Road to Peterloo album by three singers and musicians from North West England—Pete Coe, Brian Peters and Laura Smyth.)

The poetic response was not confined to social reformers and radical workers. The most astonishing outpouring of work came from isolated radical bourgeois elements in exile.

On September 5, news of the massacre reached the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) in Italy. He recognised its significance and responded immediately. Shelley’s reaction to Peterloo, what one biographer has called “the most intensely creative eight weeks of his whole life,” embodies and elevates what is greatest about his work. It underscores his importance to us now.

Franz Mehring, circa 1900

Even among the radical Romantics, Shelley is distinctive. He has long been championed by Marxists for that very reason. Franz Mehring famously noted: “Referring to Byron and Shelley, however, [Karl Marx] declared that those who loved and understood these two poets must consider it fortunate that Byron died at the age of 36, for had he lived out his full span he would undoubtedly have become a reactionary bourgeois, whilst regretting on the other hand that Shelley died at the age of 29, for Shelley was a thorough revolutionary and would have remained in the van of socialism all his life.” (Karl Marx: The Story of His Life, Harvester Press, New Jersey, 1966, p.504)

Shelley came from an affluent landowning family, his father a Whig MP. Byron’s continued pride in his title and his recognition of the distance separating himself, a peer of the realm, from his friend, a son of the landed gentry, brings home the pressures against Shelley and the fact that he was able to transcend his background.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s childhood and education were typical of his class. But bullied and unhappy at Eton, he was already developing an independence of thought and the germs of egalitarian feeling. Opposed to the school’s fagging system (making younger pupils beholden as servants to older boys), he was also enthusiastically pursuing science experiments.

He was expelled from Oxford in 1811 for publishing a tract titled “The Necessity of Atheism.” That year he also published anonymously an anti-war “Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things.” This was a fundraiser for Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, imprisoned for libel after accusing Viscount Castlereagh of mistreating United Irish prisoners. Long thought lost, a copy was found in 2006 and made available by the Bodleian Library in 2015.

Ireland was a pressing concern. Shelley visited Ireland between February and April 1812, and his “Address to the Irish People” from that year called for Catholic emancipation and a repeal of the 1800 Union Act passed after the 1798 rebellions. Shelley called the act “the most successful engine that England ever wielded over the misery of fallen Ireland.”

Shelley’s formative radicalism was informed by the French Revolution. That bourgeois revolution raised the prospect of future socialist revolutionary struggles, the material basis for which—the growth of the industrial working class—was only just emerging.

Many older Romantic poets who had, even ambivalently, welcomed the French Revolution as progressive reacted to its limitations by rejecting further strivings for liberty. Shelley denounced this, writing of William Wordsworth in 1816:

In honoured poverty thy voice did weave

Songs consecrate to truth and liberty, —

Deserting these, thou leavest me to grieve,

Thus having been, that thou shouldst cease to be.

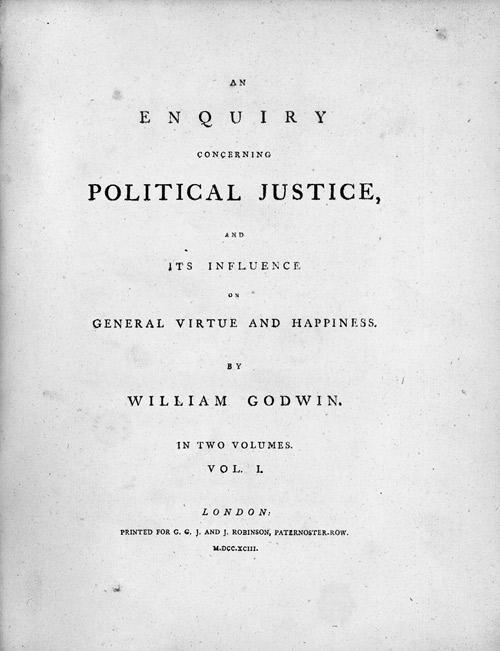

In 1811, Shelley visited the reactionary future poet laureate Robert Southey. He had admired Southey’s poetry, but not his politics, writing, “[H]e to whom Bigotry, Tyranny, Law was hateful, has become the votary of those idols in a form most disgusting.” Southey furnished Shelley with his introduction to William Godwin, whose daughter Mary would become Shelley’s wife.

Mary Shelley, 1849, Richard Rothwell

Godwin’s anarchism reflects the utopianism of a period before the emergence of a mass working class, although his novel Caleb Williams (1794) remains powerful. Shelley learned from Godwin, but was also attuned to social, political and technological developments.

Shelley’s 1813 philosophical poem Queen Mab, incorporating the atheism pamphlet in its notes, sought to synthesise Godwin’s conception of political necessity with his own thinking about continuing changes in nature. Where some had abandoned ideas of revolutionary change because of the emergence of Napoleon after the French Revolution, Shelley strove to formulate a gradual transformation of society that would still be total.

He summarised his views on the progress of the French Revolution in 1816, addressing the “fallen tyrant” Napoleon:

I did groan

To think that a most unambitious slave,

Like thou, shouldst dance and revel on the grave

Of Liberty.

He concluded:

That Virtue owns a more eternal foe

Than Force or Fraud: old Custom, legal Crime.

And bloody Faith the foulest birth of Time.

This was a statement of continued commitment to radical change and an overhaul of society. Queen Mab’s radicalism was recognised and feared. In George Cruikshank’s 1821 cartoon, “The Revolutionary Association,” one placard reads “Queen Mab or Killing no Murder.”

Eleanor Marx (middle) with her two sisters - Jenny Longuet, Laura Marx, father Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

What marks Shelley as revolutionary is his ongoing assessment of political and social developments. He was neither politically demoralised by the trajectory of the French Revolution nor tied to outmoded ways of thinking about it. He was able to some extent to carry the utopian revolutionary optimism forward into a period that saw the material emergence of the social force capable of realising the envisaged change, the working class.

His commitment to revolutionary change was “more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract,” as Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling wrote in 1888. It was a concrete striving that had to find direct political expression.

This is what makes Shelley’s response to Peterloo significant. Hearing the “terrible and important news” he wrote, “These are, as it were, the distant thunders of the terrible storm which is approaching. The tyrants here, as in the French Revolution, have first shed blood. May their execrable lessons not be learnt with equal docility!”

He began work immediately on a series of poems and essays, which he intended to be published together. In The Masque of Anarchy: Written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester, he identified Murder with “a mask like Castlereagh,” (Lord Castlereagh, the leader of the House of Commons, responsible for defending government policy), Fraud as Lord Eldon, the lord chancellor, and Hypocrisy (“Clothed with the Bible, as with light, / And the shadows of the night”) as Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth. The poem’s Anarchy is “God, and King, and Law!” Shelley’s “Anarchy we are all so afraid of is very present with us,” wrote Marx and Aveling, “[A]nd let us add is Capitalism.”

Its 91 stanzas are a devastating indictment of Regency Britain and the poem’s ringing final words—regularly trotted out by Labour leaders, with current party leader Jeremy Corbyn adapting its last line as his main slogan—still reads magnificently despite all such attempts at neutering:

And that slaughter to the Nation

Shall steam up like inspiration,

Eloquent, oracular;

A volcano heard afar.

And these words shall then become

Like Oppression’s thundered doom

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again—again—again—

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number—

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

Shelley was not making holiday speeches. The shaking off of chains is found across the Peterloo poems, and Shelley was grappling with how this might be achieved. In the unfinished essay “A Philosophical View of Reform” he tries to understand the sources of political oppression and the obstacles to its removal. There are indications he was moving away from the gradualism of Queen Mab—“[S]o dear is power that the tyrants themselves neither then, nor now, nor ever, left or leave a path to freedom but through their own blood.”

This is a revolutionary appraisal.

Shelley saw the poet’s role in that process. In the “Philosophical View,” he advanced the position, “Poets and philosophers are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” He later incorporated this into “A Defence of Poetry” (1820), explaining, “[A]s the plowman prepares the soil for the seed, so does the poet prepare mind and heart for the reception of new ideas, and thus for change.”

The Peterloo poems adopt various popular forms and styles. Addressing a popular audience with his attempt at a revolutionary understanding suggests a sympathetic response to the emergence of the working class as a political force, and the poems are acute on economic relations. As Marx and Aveling said: “…undoubtedly, he knew the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution.” In Song to the Men of England( 1819), he asked:

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

Those rich robes your tyrants wear?

Leigh Hunt; portrait by Benjamin Haydon

Shelley sent the collection to his friend Leigh Hunt’s journal, but Hunt did not publish it. Publication would, of course, have inevitably resulted in prosecution, although other publishers were risking that. When Hunt did finally publish The Mask of Anarchy in 1832, he justified earlier non-publication by arguing that “the public at large had not become sufficiently discerning to do justice to the sincerity and kind-heartedness of the spirit that walked in this flaming robe of verse.”

Advanced sections of the working class, however, understood the poems as they were intended. Shelley’s poetry was read and championed by a different audience than Hunt’s radical middle class.

As Friedrich Engels wrote in 1843 to the Swiss Republican newspaper: “Byron and Shelley are read almost exclusively by the lower classes; no ‘respectable’ person could have the works of the latter on his desk without his coming into the most terrible disrepute. It remains true: blessed are the poor, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven and, however long it may take, the kingdom of this earth as well.”

The next major upsurge of the British working class, Chartism, drew explicitly on Shelley’s inspiration and work. The direct connection between the generation of Peterloo and the Chartists, many of whom were socialists, found a shared voice in the works of Shelley.

Manchester Hall of Science, c. 1850 (formerly toe Owenite Hall of Science).

Engels continued:

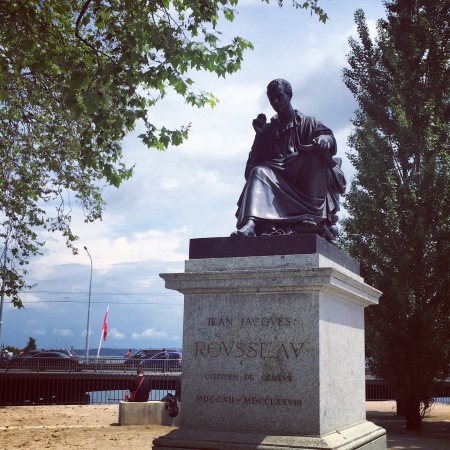

While the Church of England lived in luxury, the Socialists did an incredible amount to educate the working classes in England. At first one cannot get over one’s surprise on hearing in the [Manchester] Hall of Science the most ordinary workers speaking with a clear understanding on political, religious and social affairs; but when one comes across the remarkable popular pamphlets and hears the lecturers of the Socialists, for example [James] Watts in Manchester, one ceases to be surprised. The workers now have good, cheap editions of translations of the French philosophical works of the last century, chiefly Rousseau’s Contrat social, the Système de la Natureand various works by Voltaire, and in addition the exposition of communist principles in penny and twopenny pamphlets and in the journals. The workers also have in their hands cheap editions of the writings of Thomas Paine and Shelley. Furthermore, there are also the Sunday lectures, which are very diligently attended; thus during my stay in Manchester I saw the Communist Hall, which holds about 3,000 people, crowded every Sunday, and I heard there speeches which have a direct effect, which are made from the special viewpoint of the people, and in which witty remarks against the clergy occur. It happens frequently that Christianity is directly attacked and Christians are called ‘our enemies.’” (ibid.)

Richard Carlile published Queen Mab in the 1820s, and pirated editions produced by workers led to it being called a “bible of Chartism.”

Chartist literary criticism provides the most moving and generous testament to Shelley’s legacy in the working class. The Chartist Circular (October 19, 1839) said Shelley’s “noble and benevolent soul…shone forth in its strength and beauty the foremost advocate of Liberty to the despised people,” seeing this in directly political terms: “He believed that, sooner or later, a clash between the two classes was inevitable, and, without hesitation, he ranged himself on the people’s side.”

Friedrich Engels in his early 20s.

Engels was a contributor to the Chartist Northern Star, which had a peak circulation of 80,000. In 1847, Thomas Frost wrote in its pages of Shelley as “the representative and exponent of the future…the most highly gifted harbinger of the coming brightness.” Where Walter Scott wrote of the past, and Byron of the present, Shelley “directed his whole thoughts and aspirations towards the future.” Shelley had summed up that revolutionary optimism in Ode to the West Wind (1820): “If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?”

Shelley found his champions in the working class, quite rightly, so it is worth concluding with the stanza Frost quoted from Revolt of Islam (1817) as a marker of what should be championed in Shelley’s work, and the continued good reasons for reading him today:

This is the winter of the world;—and here

We die, even as the winds of Autumn fade,

Expiring in the frore and foggy air.—

Behold! Spring comes, though we must pass, who made

The promise of its birth—even as the shade

Which from our death, as from a mountain, flings

The future, a broad sunrise; thus arrayed

As with the plumes of overshadowing wings,

From its dark gulf of chains, Earth like an eagle springs.

‘Your sincere admirer’: the Shelleys’ Letters as Indicators of Collaboration in 1821

The Shelleys’ collaborative literary relationship never had a constant dynamic: as with the nature of any human relationship, it changed over time. In Dr. Anna Mercer’s research she aims to identify the shifts in the way in which the Shelleys worked together, a crucial standpoint being that collaboration involves challenge and disagreement as well as encouragement and support. Dr. Mercer suggests despite speculation about an increasing emotional distance between Mary and Percy, the shift in collaboration is not so black-and-white as to reduce the Shelleys’ relationship to one simply of alienation in the later years of their marriage.

INTRODUCTION

This article was originally published on 25 February 2019. It was written prior to the publication of Anna’s book on the subject matter of her essay. The book is every bit as good as I had anticipated and can be purchased directly from the publisher here. Please avoid Amazon at all costs. Another alternative is to simply place the order with your local bookshop. A full review will follow at some point in the future. In the meantime treat this post, and the linked article, as something to whet your appetite.

From the publisher’s description:

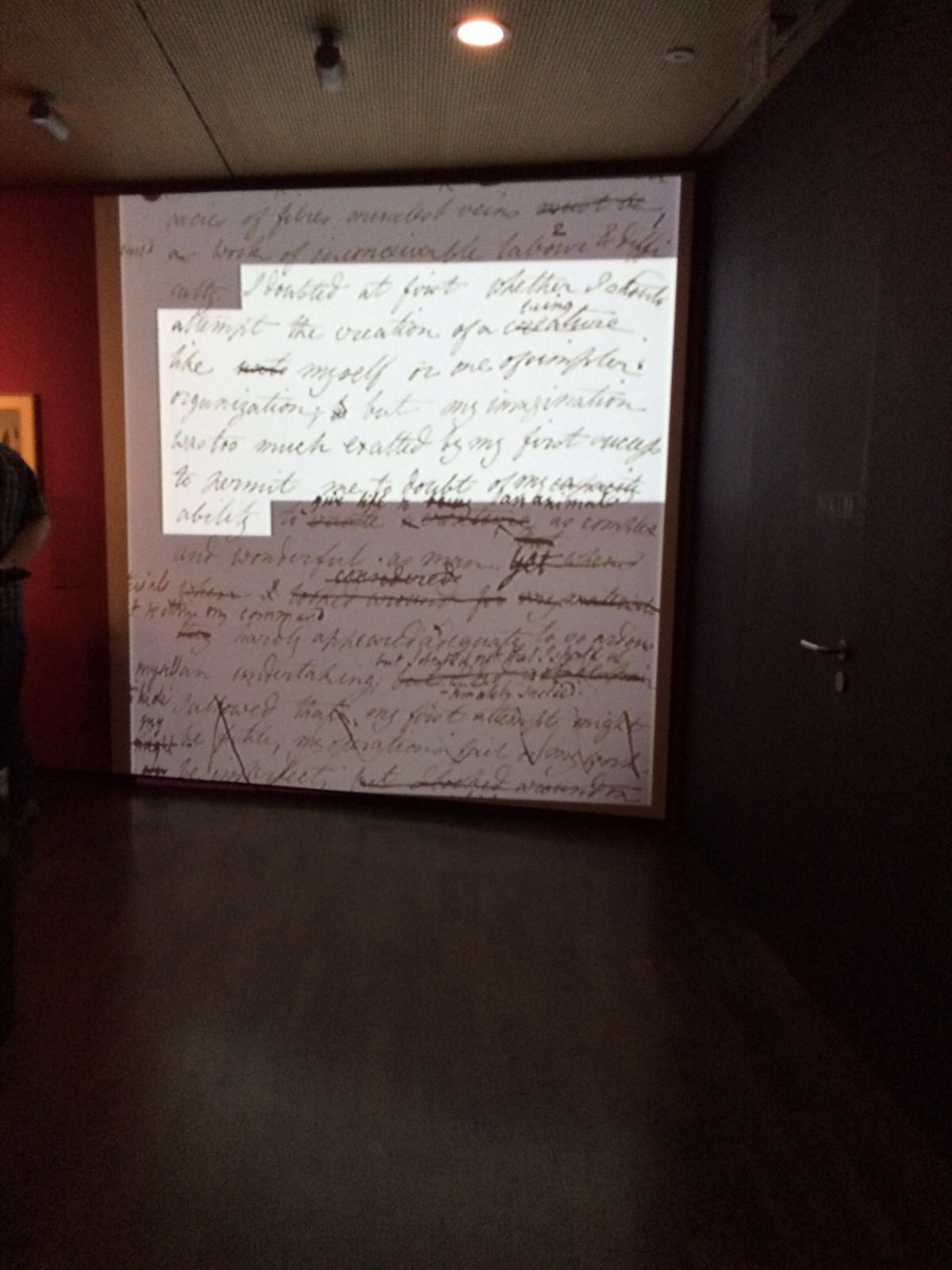

How did Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, two of the most iconic and celebrated authors of the Romantic Period, contribute to each other’s achievements? This book is the first to dedicate a full-length study to exploring the nature of the Shelleys’ literary relationship in depth. It offers new insights into the works of these talented individuals who were bound together by their personal romance and shared commitment to a literary career. Most innovatively, the book describes how Mary Shelley contributed significantly to Percy Shelley’s writing, whilst also discussing Percy’s involvement in her work.

A reappraisal of original manuscripts reveals the Shelleys as a remarkable literary couple, participants in a reciprocal and creative exchange. Hand-written evidence shows Mary adding to Percy’s work in draft and vice-versa. A focus on the Shelleys’ texts – set in the context of their lives and especially their travels – is used to explain how they enabled one another to accomplish a quality of work which they might never have achieved alone. Illustrated with reproductions from their notebooks and drafts, this volume brings Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley to the forefront of emerging scholarship on collaborative literary relationships and the social nature of creativity.

And now the original article from 25 February of this year:

2018 was a bad year for the reputation of Percy Shelley (as opposed to the boom year of 2017 about which I wrote in Shelleyan Top Ten Moments - 2017). 2018 was the year we celebrated the bicentennial of Frankenstein. There were conferences, commemorative coins, plays, movies, articles, readings and even biographies. Most of them were truly amazing. For example, the extraordinary, world-wide Frankenreads event staged on Hallowe’en by the Keats-Shelley Association of America (I wrote about that in Frankenstein Is Coming To Your Neighbourhood ). It was truly a joy to see so many people coming together to discover celebrate Mary’s genius. It could also have been used as an opportunity to shine a light on Mary’s collaborator and husband, Percy Shelley. But that did not happen.

The history of Percy’s reception by the pubic has varied widely over the centuries and has been a subject of many a book. Almost unknown during his life, he came to be lionized by the Victorian public for almost all the wrong reasons - presented as a somewhat simpering, juvenile poet who was yet capable of feats of great lyrical accomplishment. This is a false image of Percy that has persisted to this day. Meanwhile the working class has their own version of Shelley - the fire-breathing radical known to Owens, Engels, Ghandi and Marx of whom the latter remarked, “[Shelley] would always have been in the vanguard of socialism”. I wrote about this phenomenon in My Father’s Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys. Then came TS Eliot and the New Critics in the early part of the 20th Century. Whether through malice or sheer carelessness these folks focused on the fake Shelley created by the Victorians and set out, consciously and deliberately, to destroy his reputation forever. And they very nearly succeeded. Shelley disappeared from sight for decades. The process of recovery only began in the 1950s and 60s thanks to scholars such as Milton Wilson (with whom I had the luck to later complete my masters at the University of Toronto), the great Kenneth Neill Cameron and Earl Wasserman. The recovery was for the most part limited to the academic setting.

After 2017, there was reason to hope that Percy would re-enter the mainstream with an assist from his now much more famous wife. Such hope was founded on the fact that Percy played a small but universally acknowledged role in the creation of Frankenstein. That we understand his role in the creation of the novel is thanks to the meticulous research of Charles Robinson whose book The Original Frankenstein (Penguin Random House) was published with the byline: “Mary Shelley with Percy Shelley”. Perhaps, I had hoped, by shining a light on this fact, we might be able to lead the public to a better understanding of his own profound contributions to our culture. Alas no, and in some cases the portrait that was created in 2018 of Percy departs so far from the truth as to be laughable - as in the case of Haifaa al Mansour’s lamentable teen-angst bio-pic Mary Shelley. I reviewed this movie in my post, The Truth Matters. Those who have had the misfortune of watching this movie may have noticed that I have taken one of the stills from the movie to use as the background to the title page of my post. This image which shows Mary and Percy actually in love with one another may be one of the only accurate details from the entire movie.

Anna Mercer, on the other hand, is an expert a relatively new field: understanding the extent of the collaborative literary relationship that existed between Percy and Mary from their initial meeting in 1814 through to Percy’s death in 1822, as well as considering Mary’s later work. Dr. Mercer is about to publish a book (with Routledge) that aims to identify the textual connections between the works of the two authors, considering the Shelleys’ relationship in terms of literary and stylistic ideas, as opposed to purely biographical studies.

What follows will offer you an insight into her incisive and fascinating work. I can’t wait for the book.

‘Your sincere admirer’: the Shelleys’ Letters as Indicators of Collaboration in 1821 — by Dr. Anna Mercer

The Shelleys’ collaborative literary relationship never had a constant dynamic: as with the nature of any human relationship, it changed over time. In my research I aim to identify the shifts in the way in which the Shelleys worked together, a crucial standpoint being that collaboration involves challenge and disagreement as well as encouragement and support. The Shelleys’ collaborative peak was the work on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1816-1818 (to which Percy Shelley made corrections and alterations). Interest in the Shelleys’ relationship post-1818 suggests that they were not working as closely in the four years immediately preceding Percy’s death in 1822. Fascinating and insightful biographies of the couple, such as Daisy Hay’s Young Romantics, suggest that Mary worked alone on her novel Valperga (published in 1823), and Percy increasingly engaged in literary discussions with others. Evidence for this is in part based on the significance of Percy’s 1821 semi-autobiographical poem Epipsychidion, ‘an idealised history of my life and feelings’,[1] which not only contains a thinly-veiled criticism of Mary’s character, but is in many ways a love poem addressed to another woman, Emilia Viviani. Percy actively hid the poem from Mary. She did not fair copy the poem, and it arrived at the publishers in Percy’s own hand; this is unusual in that Mary was Percy’s ‘usual copyist’.[2] Daisy Hay writes of the Shelleys in 1821:

Shelley’s interest in Emilia slowly waned over the course of 1821 and dissipated by the time of her marriage to an Italian nobleman in September of that year. But the interlude widened the developing rift between Shelley and Mary, and made her more cautious in both her emotional and her intellectual engagement with him.[3]

However, despite this suggesting that the creative process of composition becomes something Percy hides from Mary, I want to suggest that the shift in collaboration is not so black-and-white as to reduce the Shelleys’ relationship to one simply of alienation in the later years of their marriage. One step towards doing this is to consider the Shelleys’ extant letters to each other in these later years. This blog focuses in particular on the letters of 1821 in order to support my suggestion.

Percy Shelley by Amelia Curran. National Portrait Gallery.

Percy’s letters to Mary show a keen intellectual interest in the progress of written work, the potential growth of his own mind, and Mary’s development as a novelist. Entangled within this are demonstrations of remarkable intimacy and tenderness. It is the combination of intellect and genuine affection that marked the Shelleys’ relationship from their initial meeting and dramatic elopement in 1814. A letter from Percy to Mary in July 1821, shows this combination of love and intellectual musings:

My dearest love – […] I spent three hours this morning principally in the contemplation of the Niobe, & of a favourite Apollo; all worldly thoughts & cares seem to vanish from before the sublime emotions such spectacles create: and I am deeply impressed with the great difference of happiness enjoyed by those who live at a distance from these incarnations of all that the finest minds have conceived of beauty, & those who can resort to their company at pleasure. What should we think if we were forbidden to read the great writers who have left us their works. – And yet, to be forbidden to live at Florence or Rome is an evil of the same kind & scarcely of less magnitude. […] Kiss little Babe, and how is he – but I hope to see him fast asleep to-morrow night. – And pray dearest Mary, have some of your Novel prepared for me for my return.[4]

Percy’s ekphrastic descriptions of his reaction to the statues in the Uffizi Palace, Florence are divulged to Mary here in detail. Beyond expecting Mary to understand this response to such artwork, the consideration of the sculptures in Italy is meant to conjure up for his wife a sense of shared experience: they had been living in the country since 1818 and had been on travels together in Europe since the year that they met. In describing his pleasure of experiencing Italy, Percy conveys to Mary his satisfaction in their living there, crucially in relation to the intellectual stimulation it offers, and in turn more subtly by implying her presence there adds to this satisfaction. Percy shows affection for his young son (something he is often criticised for failing to do) and signs off the letter by reminding Mary of her own toil in literature: the anticipation of her novel, Valperga, implies Percy’s interaction with Mary on this work, too. Another letter from Percy to Mary dated August 10th 1821 explores Percy’s interest in Mary’s work:

How is my little darling? And how are you, & how do you get on with your book. Be severe in your corrections, & expect severity from me, your sincere admirer. – I flatter myself you have composed something unequalled in its kind, & that not content with the honours of your birth & your hereditary aristocracy, you will add still higher renown to your name.[5]

Percy is at once concerned with his wife’s progress in writing: ‘expect severity from me’ implies Percy will be critiquing the work. Yet he is also her ‘sincere admirer’ and sees her future legacy as something dependent on her own genius and not just because of her famous literary parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Mary Shelley by R. Rothwell. National Portrait Gallery.

Unfortunately there is only one extant letter from Mary Shelley to Percy Shelley written in 1821. However, also in 1821 Mary Shelley writes a postscript on Percy’s letter to Thomas Love Peacock on March 21st showing a shared intimacy in communication with others. Likewise, Percy completes Mary’s letter to Claire Clairmont a few days later in April.[6] The one letter from Mary to Percy we have from this particular year is less concerned with intellectual affairs but shows the Shelleys’ reliance on one another in a time of crisis. Following the discovery of the ‘Hoppner scandal’, in which the Shelleys were accused of various wrongdoings (the complex details of which I cannot explore fully here, but are well worth reading up on; this is an intriguing unsolved mystery in the Shelleys’ biography), Mary Shelley writes to her husband:

Shocked beyond all measure […] I wrote to you with far different feelings last night – beloved friend – our bark is indeed tempest tost but love me as you have ever done & God preserve my child to me and our enemies shall not be too much for us.[7]

This letter explicitly recalls a much earlier letter written by Mary in 1814 to Percy:

we will defy our enemies & our friends (for aught I see they are all as bad as one another) and we will not part again.[8]

This shows a united front and a defiance that prevails in the Shelleys’ relationship: Mary sees ‘enemies’ as something to be challenged by the Shelleys as a couple, in both 1814 and 1821.

The Grave of Percy Shelley, Non-Catholic Cemetery, Rome.

However, there is evidence elsewhere that intellectual discussions remained a primary concern for Mary in 1821. Mary Shelley writes to Maria Gisborne in November: ‘Do you hear anything of Shelley’s Hellas?’ Hellas was completed by Percy in late October, and is one of the few works of Percy Shelley’s to be published in his lifetime (it was published in February 1822). Although, like Epipsychidion, the manuscript fair copy of Hellas wasn’t sent to the publishers in Mary’s hand,[9] the inclusion of Mary’s queries on the work in this letter show her awareness and possible involvement in the toil required in order to bring this poem to press. In this letter to Maria Gisborne from 1821 Mary also writes: ‘Ollier [the Shelleys’ publisher in England] treats us abominably – I should much like to know when he intends to answer S-’s last letter concerning my affair. I had wished it to come out by Christmas – now there is no hope.’[10] The Shelleys’ literary affairs – in Italy where composition occurs, and back in London where they attempt to publish – are as entangled as ever.

Perhaps most telling in Mary’s letter to Maria Gisborne is the wistful sentence: ‘If Greece be free, Shelley and I have vowed to go, perhaps to settle there, in one of those beautiful islands where earth, ocean, and sky form the Paradise’. Written in November 1821, how strongly this recalls Percy Shelley’s own letter to his wife on 16th August 1821 expressing the wish to relocate to a remote island paradise:

My greatest content would be utterly to desert all human society. I would retire with you & our child to a solitary island in the sea, would build a boat, & shut upon my retreat the floodgates of the world. – I would read no reviews & talk with no authors. – If I dared trust my imagination, it would tell me that there were two or three chosen companions beside yourself whom I should desire. – But to this I would not listen. – Where two or three are gathered together the devil is among them, and good far more than evil impulses – love far more than hatred – has been to me, except as you have been it’s object, the source of all sorts of mischief. So on this plan I would be alone & would devote either to oblivion or to future generations the overflowings of a mind which, timely withdrawn from the contagion, should be kept fit for no baser object.[11]

The Grave of Mary Shelley, The Parish Church of St Peter, Bournemouth.

END NOTES

[1] P B Shelley, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley Vol. II ed. by Frederick L. Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964) 18 June 1822, p. 434.

[2] Newman Ivey White, Shelley Vol II (London: Secker and Warlburg, 1947), p. 255.

[3] Daisy Hay, Young Romantics (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), p. 206.

[4] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 31st July 1821, p. 313,

[5] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 10th August 1821, p. 324.

[6] Mary W Shelley, The Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (3 vols) Vol I ed. by Betty T. Bennett (London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980 repr. 1991), pp. 186-187.

[7] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 204.

[8] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 5.

[9] It was in the hand of Edward Williams.

[10] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 209.

[11] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 15 August 1821, p. 339.

[12] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 210.

[13] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 450.

This article was originally published in Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 on 8 June 2015. It was published under a Creative Commons licence pursuant to which “all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author.”

More about the Journal: “Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 is an open-access journal that is committed to foregrounding innovative Romantic-studies research into bibliography, book history, intertextuality, and textual studies. To this end, we pubRomanticlish material in a number of formats: peer-reviewed articles, reports on individual/group research projects, bibliographical checklists, biographical profiles of overlooked Romantic writers and book reviews of relevant new research. Find out more by clicking here.”

Frankenstein, a Stage Adaptation. Review by Anna Mercer

The last stage production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I saw was a wonderful experience. The Royal Opera House’s ballet version of the novel was captivating and reflected the text’s themes of pursuit and terror with a striking intensity.[i] I’m always wary of adaptations of things I love, but after my positive experience at the ballet in London, I decided to go along to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was visiting New York. This new production by Ensemble for the Romantic Century was held in the Pershing Square Signature Center, a lovely venue. But the play itself was a disappointment overall, with only a few redeeming features.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Directed by Donald T. Sanders. A Production of Ensemble for the Romantic Century. Performed at the Irene Diamond Stage at the Pershing Square Signature Center, New York City.

A review by Anna Mercer.

The last stage production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I saw was a wonderful experience. The Royal Opera House’s ballet version of the novel was captivating and reflected the text’s themes of pursuit and terror with a striking intensity.[i] I’m always wary of adaptations of things I love, but after my positive experience at the ballet in London, I decided to go along to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was visiting New York. This new production by Ensemble for the Romantic Century was held in the Pershing Square Signature Center, a lovely venue. But the play itself was a disappointment overall, with only a few redeeming features.

The Royal Opera's adaptation of Frankenstein, which ran from 2015-16.

One of the many differences between this play and the ballet was the inclusion of Mary Shelley herself as a character. It is always exciting to hear Mary Shelley’s words read aloud on stage, and in this case it was not just the text of her “hideous progeny,” but also excerpts from her letters and journals that were dramatized onstage. However, there were some strange modifications. The composition of the novel is moved to 1819. This is clearly because those behind the production had chosen to emphasise that famous interpretation of Frankenstein as a thinly-veiled account of Mary Shelley’s grief at the loss of her young children. Such readings are outdated and limited, but they create tension and emotion onstage, something played to full effect here by the actors (who, incidentally, use American accents). Other reviewers also disliked the representations of Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley – The New York Times critic Laura Collins-Hughes wrote that “Mia Vallet’s Mary and Paul Wesley’s Percy are jarringly contemporary in affect and lack a vital spark.”[ii]

Moreover, the play – as sadly seems to be the norm in dramatisations of the Shelleys’ lives – pits Percy and Mary against each other. This seems to be for two reasons. Firstly, the tension creates “comic” effect; secondly, it works to champion Mary as a hidden genius underappreciated by her husband. Mary is trying to write, but is visibly exasperated by the comments made by Percy. There is some truth in this – he did suggest adding more polysyllabic, Latinate terms to the Frankenstein manuscript, as you can see for yourself by visiting the (free) online Shelley-Godwin Archive.[iii] However, Mary’s eye-rolling in this scene is added for dramatic effect; the writer/director encourages the audience’s laughter because of her exasperation. We are meant to see Percy’s suggestions as unhelpful, to Mary, to anyone. The lack of any mention of Percy’s literary achievements (besides some short lyrics – none of the longer, philosophical poems) makes his input seem even more arrogant. The play seeks a cheap laugh by entreating a modern audience to mentally respond with: “that’s no improvement! What a pompous guy that Shelley is.”

From "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein," which ran at the Irene Diamond Stage until January 7.

The result is a negative image of both authors. Although space does not permit me to explain more here, most Shelley scholars now agree that Mary and Percy were two participants in a reciprocal collaborative exchange. Mary Shelley invited Percy’s comments on Frankenstein, her first novel. Seek out the work of Charles E. Robinson, a late English Professor who knew the Frankenstein manuscripts better than anyone, and you will find that his commentary explains the two-way creative discussions that went into producing the text.[iv] Percy’s alterations were accepted and included by Mary and they appear in the final published version. As such, any implication that Mary disapproved of his involvement is condescending to her, as it paints her as a pushover and a victim. In presenting Percy as a patronising partner to Mary, the play actually ends up patronising Mary herself.

The National Theatre's stage production of Frankenstein premiered in 2011.

Mary’s father William Godwin is similarly represented as a bully. However, there were some positive aspects of the production as a whole: the set was gorgeous and complex (I speak as someone with no experience in theatre production and set design, I might add!), and the Creature – as is often the case – steals the show. Robert Fairchild’s writhing movements onstage were striking, and his performance was clearly very much influenced by the Danny Boyle production at the National Theatre with Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch. The score – including works by Liszt, Bach, and Schubert on oboe, piano, organ, and harpsichord – and Fairchild’s obvious talent as a dancer made certain scenes from the novel a real success. The mezzo soprano (Krysty Swann) was also a delight.

I understand that tension and misery of experience, including death and isolation, create more drama for a theatre production than an account of the social nature of creativity or the true story behind the genesis of one of the greatest novels in English literature. But I am disappointed by this work of art that ends up crippling another work of art. Those who are unfamiliar with Mary’s oeuvre and talents would leave misinformed and uninterested. For Mary Shelley fans, there were no new insights here, nor was it particularly enjoyable. The focus on Frankenstein and literally nothing else she ever wrote (besides her letters and journals) is becoming perhaps a little tiring, but I hope such a trend is peculiar to this bicentenary year, and that things might improve in the future.

Footnotes

[i] For more on the Royal Opera’s adaptation of Frankenstein, see my review here.

[ii] You can find the New York Times’ full review here.

[iii] Find this excellent archive here.

[iv] Professor Robinson’s long list of books includes an edition of Frankenstein manuscripts, entitled The Frankenstein Notebooks and The Original Frankenstein. You can find an excellent version of Frankenstein, with an introduction written by Robinson, here – but please, buy it from your local bookstore!

Anna Mercer completed her PhD on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley at the University of York in 2017. She has also studied at the University of Cambridge (Jesus College) and the University of Liverpool. She currently works at Keats House, Hampstead and as the Director of Communications for the Keats-Shelley Association of America. Her first monograph will be published by Routledge in 2019. She is on Twitter (@annamercer_) and you can visit her blog here:

The Politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley is a poet and thinker whose ideas have uncanny application to the modern era. His atheism, humanism, socialism, feminism, vegetarianism all resonate today. His critiques of the tyranny and religious oppression of the early 19th century seem eerily applicable to the early 21st century. He is the man who first conceived the concept of massive, non-violent protest as the most appropriate and effective response to authoritarian oppression. I have written about this in Shelley in our Time and What Should We Do to Resist Trump? But it may come as a surprise to many to learn Shelley also turned his mind to issues such as economics and the English national debt.

Today, the British government frames the argument around national debt by referring to the need for ‘us’ to make sacrifices or the fact that ‘we’ have been living beyond ‘our’ means and need austerity to survive economically. Despite evidence to the contrary, this ideology resonates with many people who think that in some way, we are all responsible for the financial crisis. We live within this widespread, false ideology, and some of us fight against it. However, a look back to the nineteenth century reveals that this fight was already taking place, and that capitalism was employing many of the tricks it still uses today. Jacqueline Mulhallen looks at the political life of the radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in her new biography and reveals that there was much more to him than first meets the eye.

Shelley is a poet and thinker whose ideas have uncanny application to the modern era. His atheism, humanism, socialism, feminism, vegetarianism all resonate today. His critiques of the tyranny and religious oppression of the early 19th century seem eerily applicable to the early 21st century. He is the man who first conceived the concept of massive, non-violent protest as the most appropriate and effective response to authoritarian oppression. I have written about this in Shelley in our Time and What Should We Do to Resist Trump? But it may come as a surprise to many to learn Shelley also turned his mind to issues such as economics and the English national debt. For example:

"I forbear to address you as I had designed on the subject of your income as a public creditor of the English Government as it seems you have not the exclusive management of your funds...In vindication of what I have already said allow me to turn your attention to England at this hour. [There follows a detailed examination of the national debt and the unstable political situation in England] The existing government, atrocious as it is, is the surest party to which a creditor can attach himself - he may reason that "it may last my time" - though in the event, the ruin is more complete than in the case of popular revolution."

- Shelley to John and Maria Gisborne, Florence, 6 November 1819

This quote is drawn from a series of letters from Shelley to his friends John and Maria Gisborne. Shelley is discussing the fact that John had invested his money in "British Funds". These were a sort of "savings bond" used to finance England's staggering national debt. By 1815 the national debt had risen to over a billion pounds -- more than 200% of the GDP. Compare this to the modern era:

To the end of his life, Shelley continually pestered John to remove his money from the Funds - he expected ruin for his friend. Shelley's letters demonstrate that his genius extended far beyond poetry and philosophy. The letter also contains the first reference to A Philosophical View of Reform, which Shelley wrote between November 1819 and May 1820: he notes that he had "deserted the odorous gardens of literature to journey across the great sandy desert of Politics." And what an epic journey it turned out to be.

This letter shows a side of Shelley that few have ever seen. and today's guest article by Jacqueline Mulhallen brings this side into sharp focus. The article appeared on the website of Pluto Press, publisher of Jacqueline's book, Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet and Revolutionary. You can find it here. And you can read my own review here. Without further ado, here is the article.

A Philosophical View of Reform: The Politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley

by Jacqueline Mulhallen

Today, the British government frames the argument around national debt by referring to the need for ‘us’ to make sacrifices or the fact that ‘we’ have been living beyond ‘our’ means and need austerity to survive economically. Despite evidence to the contrary, this ideology resonates with many people who think that in some way, we are all responsible for the financial crisis. We live within this widespread, false ideology, and some of us fight against it. However, a look back to the nineteenth century reveals that this fight was already taking place, and that capitalism was employing many of the tricks it still uses today. Jacqueline Mulhallen looks at the political life of the radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in her new biography and reveals that there was much more to him than first meets the eye.

- Introduction from Pluto Press

Debt in the Time of Shelley

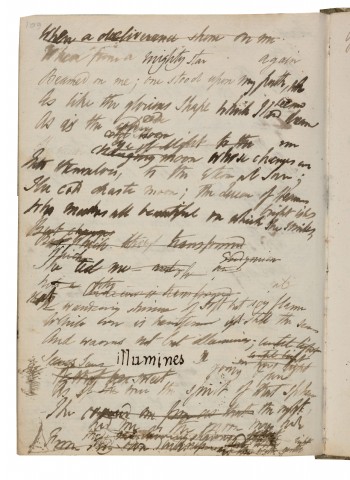

Shelley's drawing affixed to his copy of A Philosophical View of Reform. It demonstrates a quite extraordinary gift for draughtsmanship.

‘In 1819, Percy Shelley was writing A Philosophical View of Reform. In its pages, he is clear about whom he considered responsible for the national debt, which at that time was bigger than it had ever been before – in 1815 the interest amounted to £37,500,000. Shelley, like many people today, fought against the common consensus and blamed the bankers and the nation’s financial institutions. He clearly expressed his contempt in them; the ‘stock jobbers, usurers, directors, government pensions, country bankers: a set of pelting wretches who think of any commerce with their species as a means not an end’ and whose position in society he believed was based on fraud. Shelly himself surprisingly came from the landed aristocracy, however he had no love for this class either, as their existence was built upon force and was what he labelled ‘a prodigious anomaly’. He also talked of the rise of the newly wealthy as a different form of aristocracy who created a double burden on those whose labour created ‘the whole materials of life’. He could see that they together formed one class – ‘the rich’.

It was obvious to Shelley that the national debt had been contracted by ‘the whole mass of the privileged classes towards one particular portion of those classes’ – just as is the case today. ‘If the principal of this debt were paid … it would be the rich who alone could, as justly they ought, to pay it … As it is, the interest is chiefly paid by those who had no hand in the borrowing and who are sufferers in other respects from the consequences of those transactions in which the money was spent’.

Austerity and War in the Nineteenth Century

A Page from A Philosophical View of Reform.

Shelley also expressed what he saw as a clear connection between austerity and war. The national debt was ‘chiefly contracted in two liberticide wars’, against the American revolutionaries and then the French revolutionaries. The money borrowed could have been spent in making the lives of working people better. As it was, the majority of the people in England were observed by Shelley as ‘ill-clothed, ill-fed, ill-educated’. After the Napoleonic Wars unemployment soared and returning soldiers were often found begging in the streets. The condition of all the classes ‘excepting those within the privileged pale’ was ‘singularly unprosperous’, allowing Shelley to comment, ‘The power which has increased is the power of the rich’.

Shelley also believed that anyone whose ‘personal exertions’ were ‘more valuable to him than his capital’ such as surgeons, mechanics, farmers and literary men (people often described as middle class) were only ‘one degree removed from the class which subsists by daily labour’ and therefore should not be classed with the rich. However, Shelley returned again and again to his obsession, the situation of the worker. His essay A Philosophical View of Reform, which on the surface was about the possibilities of reforming the English parliament to make it more representative, contained within it a message about how reform would not be enough. Why demand universal suffrage, he asks, when you can demand a Republic: ‘the abolition of, for instance, monarchy and aristocracy, and the levelling of inordinate wealth, and an agrarian distribution, including the parks and chases of the rich?’

The Radical Questions of the Day

As a boy, Shelley was probably involved in anti-slavery activity in his home town of Horsham in Sussex. His father had been elected to Parliament as an MP to support the anti-slave trade bill in 1790, although some corrupt practices meant that he lost his seat before he was able to vote on the question. But in 1807, the year the slave trade was abolished, the inhabitants of Horsham were particularly active, with a close family friend of the Shelleys standing on an anti-slavery platform.

Shelley also supported the independence of Ireland, arguing that the repeal of the Act of Union with England was a more important issue than Catholic Emancipation (although he supported the campaign for Catholics to sit in the British Parliament). Shelley admired Thomas Paine, the author of The Rights of Man and Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women. He went so far as to try to renounce his inheritance as a member of the wealthy landowning class in favour of his sisters, though he only succeeded in transferring some of this wealth to his brother. He supported women writers including his own wife, Mary Shelley, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and author of Frankenstein.

Percy Shelley believed that equality was the natural state. He was ahead of his time. And yet, in the twenty-first century we still labour in an unequal, class society, and we still live with racism, exploitation and sexism. As is well known, the gap between the rich and the poor has widened to become greater than at any time in the last fifty years.

Legacy

Despite living 200 years ago, Shelley’s legacy is very much with us today, even if it was ignored and ridiculed in his lifetime. He attempted to get A Philosophical View of Reform published in England, but the publisher he submitted the manuscript to ignored him. Not having other contacts in England, Shelley left the essay unfinished. It was not published until 100 years after his death and so was never read by his contemporaries, although he recycled parts of it into his Defence of Poetry. Even nowadays it is not often read or discussed, and it deserves to be better known. Shelley should be honoured as a political thinker, as well as a magnificent poet. In A Defence of Poetry, Shelley describes poets as the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’ and his example shows the way in which poets can be closely involved with the political issues of the day.

Jacqueline Mulhallen wrote and performed in the plays Sylvia and Rebels and Friends. She is the author of The Theatre of Shelley (Open Book Publishers, 2010) and contributed a chapter on Shelley to The Oxford Handbook to Georgian Theatre (OUP, 2014), which was shortlisted for the Theatre Book Prize 2015.

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet and Revolutionary is available to buy from Pluto Press. The foregoing article is reproduced with their kind permission. Visit Jacqueline's website here.

Why the Shelley Conference? By Anna Mercer

The Shelley Conference takes place in London at Institute for English Studies on the 15th and 16th of September. The keynote speakers are Prof. Nora Crook, Prof Kelvin Everest and Prof. Michael O’Neill. The conference is open to everyone - which is just how Shelley would have liked it. He would have also liked the fact that he and his wife are treated as co-equals and creative collaborators. I myself am honoured to be part of the conference and will be speaking on what I call "Romantic Resistance" - Shelley's strategies for opposing political and religious tyrannies. They are surprisingly applicable to our times! Here is co-organizer Anna Mercer on how this amazing conference came

The Shelley Conference takes place in London at Institute for English Studies on the 15th and 16th of September.

The keynote speakers are Prof. Nora Crook (Anglia Ruskin University), Prof Kelvin Everest (University of Liverpool) and Prof. Michael O’Neill (Durham University). The conference is open to everyone - which is just how Shelley would have liked it. He would have also liked the fact that he and his wife are treated as co-equals and creative collaborators. I myself am honoured to be part of the conference and will be speaking on what I call "Romantic Resistance" - Shelley's strategies for opposing political and religious tyrannies. They are surprisingly applicable to our times! Here is co-organizer Anna Mercer on how this amazing conference came to be:

Why the Shelley Conference? By Anna Mercer

Anna Mercer

I was motivated to create ‘The Shelley Conference 2017’ because of my own frustration with the fact that there is no regular event, academic or otherwise, dedicated solely to the study of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s works. Neither is there such an event for Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. The other Romantics enjoy fantastic annual symposiums where experts and lovers of great literature meet; for example I have been lucky enough to attend the Keats Conference in Hampstead and the Coleridge Conference in the South West (held in Bristol, or Somerset). These carefully planned gatherings of world-renowned speakers and literature enthusiasts include walks and other activities in the surroundings loved by Keats and Coleridge. They encourage postgraduate participation, and are jovial and create a sense of community. I know there is also a similar event for Wordsworth in Grasmere; why is there no such event for PBS or MWS?

My research (on the collaborative literary relationship of PBS and MWS) led me to develop the idea of a conference that celebrated both authors. Contemporary criticism thankfully no longer wastes time belittling MWS as minor in comparison to PBS’s genius, or depicting PBS as a tyrannical, corrupt editor of her work. The birth of ‘The Shelley Conference’ was set to chime with this refreshing lack of conflict in contemporary study, something that I admit my work in particular seeks to broaden and develop, particularly through the use of manuscript evidence, in order to understand how the Shelleys worked in a reciprocal literary exchange.

The Shelleys in popular culture, however, remain separated and many misconceptions about their relationship persist in the public consciousness (see for example my review of ‘The Secret Life of Books: Frankenstein’ broadcast on BBC4). I have become increasingly aware that now such Shelley-related events are not limited to a small group of academics, and with social media and the help of other Shelley platforms (including this one!), the Shelleys can be identified for what they are actually are, and what they actually sought to represent: that is, two incredibly talented authors, who dedicated their lives to the study and writing of radical and innovative literature.

The Shelley of the conference title remains ambiguous. Furthermore, I have clearly stated that the conference is two days on the works of PBS and MWS. Our speakers will pay attention to biographical details in order to gauge how their shared lives (and also their shared travels) influence their texts, as opposed to the texts revealing truths about their lives. Can we remove the damaging opinion that the Shelleys’ relationship was something defined by scandal, infidelity, gossip, and anti-establishment teenage pursuits? They certainly would have wished we could do so. Let us return to their writings, and not the many, many biographical speculations created by scholars and other writers, some with good intentions, some without.

It is for this reason that I am delighted to announce the breadth of papers that we have at the conference. We have panels that address philosophy, translation, the reception of these authors, editing, the Shelleys in Italy, the Shelleys and science, radical Shelley (including Graham Henderson’s paper on ‘Romantic Resistance’), utopia and dystopia, and even the Shelleys’ diets. We have speakers from all over the world including Canada and mainland Europe, and we have postgraduates speaking at various stages in their career, as well as more established academics, and other writers: novelists, independent scholars, and poets. Some panels include papers on PBS and MWS side-by-side, others focus solely on one author, with the presumption that the Q&A discussion at the end of the presentations will be broad and energetic, reaching into different spheres of knowledge, and addressing the wider Shelley circle – for example Peacock, Hogg, Claire Clairmont, the Gisbornes, and Byron.

Also, excitingly it is now, in the first part of the 21st century, that the most detailed comprehensive editions of PBS’s works are in production (The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley ed. Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook is already well advanced, with Vol VII published soon, and The Poems of Shelley ed. Kelvin Everest, G. M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan is nearing completion). Michael Rossington and Nora Crook will deliver short presentations on the progress of these editions in an optional session during the lunch break on Friday.

I would like to add that I am indebted to Kelvin Everest, an academic mentor to me since my undergraduate days. He was the pioneer of the first Shelley conferences in Gregynog, and his collection of essays that came from that time can be found here. I am honoured to say that he has been an invaluable advisor to me during this conference, and will also be delivering a keynote lecture, alongside the other plenary talks by Michael O’Neill and Nora Crook.

I also thank Michael Rossington, who similarly has delivered advice and guidance, and my coorganiser Harrie Neal (she speaks on Saturday, with a paper on ‘Mary Shelley’s post-capitalist ecology’).

See the detailed programme here.

Thank you to our sponsors – who, amongst other things, have made it possible for us to charge the reduced fee of £15 only for postgraduates and unwaged delegates:

Thanks also to the support from our host institution, the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies (CECS) at the University of York, and our venue, the Institute for English Studies (IES) in London.

I sincerely hope that the Shelley Conference may occur again in years to come – watch this space.

Sir Humphrey Davy and the Romantics - an Online Course

Professor Sharon Ruston of Lancaster University is offering a free online course through Future Learn called "Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp". These types of course are fun and informative. If you are interested in Shelley you will want to learn more about Davy because Shelley studied him closely. Shelley was one of the last great polymaths - he was well versed with a range of subjects that dwarfs most of his famous contemporaries. Science was one of them. To understand Shelley fully, you need to understand his interest in science - this course can help you to do this.

I am pleased to introduce Sharon Ruston to my readers. Sharon is a Shelley and Romantics scholar who is the Chair of the English Department at Lancaster University. Her main research interests are in the relations between the literature, science and medicine of the Romantic period, 1780-1820. Her first book, Shelley and Vitality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), explored the medical and scientific contexts which inform Shelley's concept of vitality in his major poetry. Her most recent book, Creating Romanticism: Case Studies in the Literature, Science, and Medicine of the 1790s (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) has chapters on Mary Wollstonecraft's interest in natural history, William Godwin's interest in mesmerism, and Humphry Davy’s writings on the sublime. Sharon is currently co-editing the Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy and his Circle, to be published in four volumes by Oxford University Press.

Sharon Ruston, Chair, Department of English, Lancaster University.

Sharon is offering a free online course through Future Learn called "Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp". These types of course are fun and informative. If you are interested in Shelley you will want to learn more about Davy because Shelley studied him closely. Shelley was one of the last great polymaths - he was well versed with a range of subjects that dwarfs most of his famous contemporaries. Science was one of them. To understand Shelley fully, you need to understand his interest in science - this course can help you to do this.

You can find Sharon on Twitter @SharonRuston and at Lancaster University. Here is her guest column.

This autumn you can participate in a free, online course on a man of science whom P. B. Shelley greatly admired, Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829).

Sir Humphry Davy. Thomas Phillips National Portrait Gallery, London

Anyone can sign up and all are welcome from people who know nothing about Davy to those who are already aware of just how fascinating a figure he is. Shelley was certainly interested in Davy: Shelley made copious, extensive notes on one of Davy’s most popular works Elements of Agricultural Chemistry (1813) sometime around 1820. I have speculated on why Shelley was so interested in these in my book Shelley and Vitality, which more generally considered Shelley’s interest in science and medicine.