What Shelley Means to Me

Allow me to introduce you to Oliver. Oliver popped up one day on my twitter feed. Oliver’s pronouns are they/their and they are a high school student living in Michigan. Oliver has an incredible passion for poetry and Shelley in particular. Oliver started asking for book recommendations - and they devoured them. They started doing research and bringing new findings and perspectives to our twitter feeds. Oliver started engaging with a large cross-section of the online Shelley community - ranging from amateur fans to some of the most respected academic authorities in the world!

Introduction to Oliver

Years ago when my interest in the revolutionary writer Percy Bysshe Shelley was revived, my first instinct was to create a community. I wanted to share my passion for Shelley with a wide audience. And so this site was born.

I devoted a lot of time and money to building it. But I very quickly discovered that the dictum "build it and they will come" did not operate in cyberspace! And so I needed to develop strategies to engage a wider non-academic audience. To do that I created companion amplification outlets on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. The effect was catalytic, and my audience grew rapidly around the world. For example, one of the largest audiences I have on Facebook is in Italy.

But I wanted more! And so I hired technical experts to help me with the search engine optimization of the site. It worked. Almost immediately The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley became more visible and easy to find in the audience grew again.

One audience, however, proved elusive: the younger generation. Where were they? How was I to find them? Did I have to create a TikTok site!? Perhaps I do. In any event, one day I got lucky.

Allow me to introduce you to Oliver. Oliver (they/them) is a high school student living in Midwestern United States. They popped up one day on my Twitter feed. Oliver was inquisitive and eager; asking all kinds of questions and for book recommendations among other things. They seemed particularly interested in Shelley’s more radical, political poetry and essays which was very gratifying to me personally. WhileI know they were nervous at first, that didn't prevent them from rapidly integrating into the community and interacting with an incredibly wide range of Shelleyans; including some of the most distinguished academic scholars in the world! We started to joust with Shelley-pals like Bysshe Coffey on a wide range of subjects.

It's suddenly occurred to me, that I should be asking a young person such as Oliver to write for this site. And so I did. And Oliver agreed! And am I ever glad I did and they did! What Oliver produced was heartfelt, poignant and uplifting. If I never do anything again with this site, this will be enough and I will be happy. Having fired a young person’s mind with a passion for Shelley is more than I could've hoped for. There is a forest in every acorn.

Thank you, Oliver, for you fearless, inquiring mind, thank you for taking a chance; and thank you for writing this beautiful essay. Onward!!

What Percy Bysshe Shelley Means to Me, a Young Person From Minority and Marginalized Groups

by Oliver

Shelley to me is a person who could see hope and light in the darkness that surrounds people. To me he feels like someone who was a protector. And not just a protector of his loved ones alone, but also of people who have faced harsh words from others who in order to feel better about themselves bring others down.

That man was not a poet who just wrote about politics and nature but a writer and poet for the people who can’t get up in the morning because depression and anxiety are pushing them down. He is a guardian to lost children and teenagers who have to face the fact that their parents are struggling and not listening to their needs. Shelley speaks for those who aren’t listened to by authority figures.

To me, Percy is the poet of the different and silenced people of oppressed groups. He spoke in words that may be hard to understand to some but which nonetheless get the meaning across. He writes for the lost and hurt - people who have suffered because of their oppressors. His poetry is something that should be cherished by the people for whom it was written. And it also deserves attention from the wider general public.

I look at my small collection of books I have about him and by him. They sit on my shelf and it feels like he’s always been there for me. I read his poems and seek to learn his messages. I believe that he’s been here since I first experienced loss in my life. He feels like a spirit that watches over us and swoops into our minds whenever he is needed. It seems like he’s always there when it feels like I can’t do anything right and yet I’m trying so hard to do things the right way. I learned from him that I don’t want to do everything that adults and authority figures say I must. He supports my belief that I’m my own person and don’t have to follow their way of thinking just because I’m a teenager. He supports my belief that I don’t have to conform to their ways of thinking; because I’m not like them at all. I am not a student of my school, I feel like I am a student of Shelley and my mentors in these studies.

This isn’t everything I want to say about Percy Shelley and definitely is not the last of how I’ll write and speak of him. Hopefully we will see no end to people sharing his words with others and speaking them in times when it seems right and. His legacy will be kept alive in this way!

Oliver is a high school student living in Michigan. Their favourite poem by Shelley is The Mask of Anarchy and right now they are reading Richard Holmes biography of PBS: “Shelley, The Pursuit.” However, Oliver’s favourite biography is the one by James Bieri. When asked what question they might ask Percy were they to meet him, Oliver suggested this: “How do you think people will see your life once you’re gone.” I would love to get an answer to that myself! Oliver would one day like to be a writer and a member of the Keats Shelley Association of America. You can find Oliver on Twitter here.

“Fear not for the future - Percy Shelley”

The Peterloo Massacre and Percy Shelley by Paul Bond

Paul Bond’s essay is nothing less than a tour de force encapsulating and documenting Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his own era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand his radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond.

In the early autumn, my online “Shelley Alert” trip wire came alive with a link to an article published by Paul Bond on the World Socialist Web Site (“WSWS”) under the auspices of the International Committee of the Fourth International (“ICFI”). Paul, it turns out, is an active member of the Trotskyist movement and has been writing for the WSWS since its launch in 1998. It also turns out he is an ardent admirer of Percy Shelley. That someone like Paul would be interested in Shelley and that the ICFI would publish his article about Shelley did not surprise me in the least. Though I suspect it might arouse the curiosity of a goodly portion of Shelley’s current fan base.

Before we delve further into this, let’s find out exactly what the WSWS is? Understanding this may explain a lot:

The World Socialist Web Site is published by the International Committee of the Fourth International, the leadership of the world socialist movement, the Fourth International founded by Leon Trotsky in 1938.

The WSWS aims to meet the need, felt widely today, for an intelligent appraisal of the problems of contemporary society. It addresses itself to the masses of people who are dissatisfied with the present state of social life, as well as its cynical and reactionary treatment by the establishment media.

Our web site provides a source of political perspective to those troubled by the monstrous level of social inequality, which has produced an ever-widening chasm between the wealthy few and the mass of the world's people. As great events, from financial crises to eruptions of militarism and war, break up the present state of class relations, the WSWS will provide a political orientation for the growing ranks of working people thrown into struggle.

We anticipate enormous battles in every country against unemployment, low wages, austerity policies and violations of democratic rights. The World Socialist Web Site insists, however, that the success of these struggles is inseparable from the growth in the influence of a socialist political movement guided by a Marxist world outlook.

The standpoint of this web site is one of revolutionary opposition to the capitalist market system. Its aim is the establishment of world socialism. It maintains that the vehicle for this transformation is the international working class, and that in the twenty-first century the fate of working people, and ultimately mankind as a whole, depends upon the success of the socialist revolution.

You can learn more about them here.

For those of you familiar with the radical Percy Shelley, this will, of course, make sense. Shelley has been an inspiration to those on the left from the early 1800s. I have written extensively about this in my articles “My Father’s Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys”, “Percy Bysshe Shelley in Our Time” and “Jeremy Corbin is Right: Poetry Can Change the World”.

I think the fact that the WSWS has published an extensive article exploring Shelley’s radicalism is an important and salutary moment. It should help to reconnect Shelley to a new generation of radicals. The principal reason that Shelley remains relevant today is almost exclusively connected to his radicalism. His love poetry is exquisite and reminds us that PB was a three dimensional person. But there is an enormous amount of brilliant love poetry out there; and precious little radical poetry - having said that a great deal of Shelley’s love poetry is in fact a very radical variant of love poetry.

But it is Shelley’s radicalism that makes him stand out as a giant among his contemporaries. Little wonder then that Eleanor Marx proudly declaimed in a famous speech in 1888: “We claim his as a socialist.” Shelley’s radicalism inspired generations of activists and radicals; radicals who, explicitly inspired by Shelley, went on to change the world for the better. Is there a better example of this than the effect Shelley had on Pauline Newman, one of the founders of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union? You can read more about this in my article “The Story of the Mask of Anarchy: From Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire”. And please read Michael Demson’s brilliant graphic novel of the same name. Links to buy it are in my article.

Two of the best biographies of Shelley were written by life-long members of the left. The first, Kenneth Neill Cameron (an avowed Marxist), penned The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical. The other, Paul Foot (the greatest crusading journalist of his generation), authored The Red Shelley. You can read Paul Foot’s spellbinding address to the 1981 International Marxism Conference in London here. It took me over two hundred hours to transcribe and properly footnote his speech!

For both Engels and Marx, Shelley was an inspiration:

Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

Marx:

The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of Socialism.

Eleanor Marx supplied the principle reason for these assessments of Shelley. She wrote,

More than anything else that makes us claim Shelley as a Socialist is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery.

This grim portrayal of the tyranny faced by the citizens of Shelley’s and Marx’s eras has an equally grim, modern resonance. One need to look no further than Marxist-inspired writers such as Astra Taylor (The People’s Platform) and Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) to come to grips with the fact that the situation has, if anything, got worse. Our modern “possessing class” of digital overlords threaten not simply to strip the people of their labour, but to turn our very lives into the raw materials that feed the rapacious, insatiable demands their modern “surveillance capitalism”.

However, let me turn the floor over to Paul Bond whose essay is something of a tour de force that encapsulates Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand this radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond. You can follow Paul on Twitter @paulbondwsws and the World Socialist Web Site @WSWS_Updates.

The caption photo at top is of Eleanor Marx (middle) with her two sisters - Jenny Longuet, Laura Marx, father Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Eleanor was a champion of PBS.

The Peterloo Massacre and Shelley

by Paul Bond

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, a critical event in British history. On August 16, 1819, a crowd of 60,000 to 100,000 protestors gathered peacefully on Manchester’s St. Peter’s Field. They came to appeal for adult suffrage and the reform of parliamentary representation.The disenfranchised working class—cotton workers, many of them women, with a large contingent of Irish workers—who made up the crowd were struggling with the increasingly dire economic conditions following the end of the Napoleonic Wars four years earlier.

Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest the speakers and sent cavalry of Yeomanry and a regular army regiment to attack the crowd. They charged with sabres drawn. Eighteen people were killed and up to 700 injured.

On August 16 of this year the WSWS published an appraisal of the massacre.

The Peterloo Massacre elicited an immediate and furious response from the working class and sections of middle-class radicals.

The escalation of repression by the ruling class that followed, resulting in a greater suppression of civil liberties, was met with meetings of thousands and the widespread circulation of accounts of the massacre. There was a determination to learn from the massacre and not allow it to be forgotten or misrepresented. Poetic responses played an important part in memorialising Peterloo.

Violent class conflict erupted across north western England. Yeomen and hussars continued attacks on workers across Manchester, and the ruling class launched an intensive campaign of disinformation and retribution.

At the trial of Rochdale workers charged with rioting on the night after Peterloo, Attorney General Sir Robert Gifford made clear that the ruling class would stop at nothing to crush the development of radical and revolutionary sentiment in the masses. He declared: “Men deluded themselves if they thought their condition would be bettered by such kind of Reform as Universal Suffrage, Annual Parliaments, and Vote by Ballot; or that it was just that the property of the country ought to be equally divided among its inhabitants, or that such a daring innovation would ever take place.”

Samuel Bamford (1788–1872), 'The Radical', Silk Weaver of Middleton by Charles Potter

Samuel Bamford, a reformer and weaver who led a contingent of several thousand marchers to Manchester from the town of Middleton, said he spent the evening of the massacre “brooding over a spirit of vengeance towards the authors of our humiliation.” Bamford told the judge at his trial for sedition that he would not recommend non-violent protest again.

Workers took a more direct response, even as the military were being deployed widely against the population. Despite the military presence, and press claims that the city had been subdued, riots continued across Manchester.

Two women were shot by hussars on August 20. A fortnight after Peterloo, the most affected area, Manchester’s New Cross district, was described in the London press as a by-word for trouble and a risky area for the wealthy to pass through. Soldiers were shooting in the area to disperse rioters. On August 18, a special constable fired a loaded pistol in the New Cross streets and was attacked by an angry crowd, who beat him to death with a poker and stoned him.

There was a similar response elsewhere locally, with riots in Oldham and Rochdale and what has been described by one historian as “a pitched battle” in Macclesfield on the night of August 17.

Crowds in their thousands welcomed the coach carrying Henry Hunt and the other arrested Peterloo speakers to court in Salford, the city across the River Irwell from Manchester. Salford’s magistrates reportedly feared a “tendency to tumult,” while in Bolton the Hussars had trouble keeping the public from other prisoners. The crowd shouted, “Down with the tyrants!”

While the courts meted out sharper punishment to the arrested rioters, mass meetings and protests continued across Britain. Meetings to condemn the massacre took place in Wakefield, Glasgow, Sheffield, Huddersfield and Nottingham. In Leeds, the crowd was asked if they would support physical force to achieve radical reform. They unanimously raised their hands.

These were meetings attended by tens of thousands and they did not end despite the escalating repression. The Twitter account Peterloo 1819 News (@Live1819) is providing a useful daily update on historical responses until the end of this year.

A protest meeting at London’s Smithfield on August 25 drew crowds estimated at 15,000-40,000. At least 20,000 demonstrated in Newcastle on October 11. The mayor wrote dishonestly to the home secretary, Lord Sidmouth, of this teetotal and entirely orderly peaceful demonstration that 700 of the participants “were prepared with arms (concealed) to resist the civil power.”

The response was felt across the whole of the British Isles. In Belfast, the Irishman newspaper wrote, “The spirit of Reform rises from the blood of the Manchester Martyrs with a giant strength!”

A meeting of 10,000 was held in Dundee in November that collected funds “for obtaining justice for the Manchester sufferers.” That same month saw a meeting of 10,000 in Leicester and one of 12,000 near Burnley. In Wigan, just a few miles north of the site of Peterloo, around 20,000 assembled to discuss “parliamentary reform and the massacre at Manchester.” The yeomanry were standing ready at many of these meetings.

The state was determined to suppress criticism. Commenting on the events, it published false statements about the massacre and individual deaths. Radical MP Sir Francis Burdett was fined £2,000 and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for “seditious libel” in response to his denunciation of the Peterloo massacre. On September 2, he addressed 30,000 at a meeting in London’s Palace Yard, demanding the prosecution of the Manchester magistrates.

Richard Carlile

Radical publisher Richard Carlile, who had been at Peterloo, was arrested late in August. He was told that proceedings against him would be dropped if he stopped circulating his accounts of the massacre. He did not and was subsequently tried and convicted of seditious libel and blasphemy.

The main indictment against him was his publication of Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. Like Bamford, Carlile also concluded that armed defence was now necessary: He wrote, “Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform should never go unarmed—retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.”

In Chudleigh, Devon, John Jenkins was arrested for owning a crude but accurate print of the yeomanry charging the Peterloo crowd when Henry Hunt was arrested. A local vicar, a magistrate, informed on Jenkins, whose major “crime” was that he was sharing information about Peterloo. Jenkins was showing the print to people, using a magnifying glass in a viewing box. The charge against Jenkins argued that the print was “intended to inflame the minds of His Majesty’s Subjects and to bring His Majesty’s Soldiery into hatred and contempt.”

Against this attempt to suppress the historical record there was a wide range of efforts to preserve the memory of Peterloo. Verses, poems and songs appeared widely. In October, a banner in Halifax bore the lines:

With heartfelt grief we mourn for thoseWho fell a victim to our causeWhile we with indignation viewThe bloody field of Peterloo.

Anonymous verses were published on cheap broadsides, while others were credited to local radical workers. Many recounted the day’s events, often with a subversive undercurrent. The broadside ballad, “A New Song on the Peterloo Meeting,” for example, was written to the tune “Parker’s Widow,” a song about the widow of 1797 naval mutineer Richard Parker.

Weaver poet John Stafford, who regularly sang at radical meetings, wrote a longer, more detailed account of the day’s events in a song titled “Peterloo.”

The shoemaker poet Allen Davenport satirised in song the Reverend Charles Wicksteed Ethelston of Cheetham Hill—a magistrate who had organised spies against the radical movement and, as the leader of the Manchester magistrates who authorised the massacre, claimed to have read the Riot Act at Peterloo.

Ethelston played a vital role in the repression by the authorities after Peterloo. At a September hearing of two men who were accused of military drilling on a moor in the north of Manchester the day before Peterloo, he told one of them, James Kaye, “I believe that you are a downright blackguard reformer. Some of you reformers ought to be hanged; and some of you are sure to be hanged—the rope is already round your necks; the law has been a great deal too lenient with you.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Clint (after Amelia Curran) c. 1829

Ethelston was also attacked in verse by Bamford, who called him “the Plotting Parson.” Davenport’s “St. Ethelstone’s Day” portrays Peterloo as Ethelston‘s attempt at self-sanctification. Its content is pointed— “In every direction they slaughtered away, Drunken with blood on St. Ethelstone’s Day”—but Davenport sharpens the satire even further by specifying the tune “Gee Ho Dobbin,” the prince regent’s favourite. (These songs are included on the recent Road to Peterloo album by three singers and musicians from North West England—Pete Coe, Brian Peters and Laura Smyth.)

The poetic response was not confined to social reformers and radical workers. The most astonishing outpouring of work came from isolated radical bourgeois elements in exile.

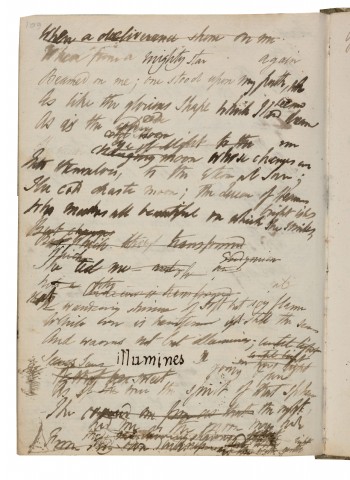

On September 5, news of the massacre reached the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) in Italy. He recognised its significance and responded immediately. Shelley’s reaction to Peterloo, what one biographer has called “the most intensely creative eight weeks of his whole life,” embodies and elevates what is greatest about his work. It underscores his importance to us now.

Franz Mehring, circa 1900

Even among the radical Romantics, Shelley is distinctive. He has long been championed by Marxists for that very reason. Franz Mehring famously noted: “Referring to Byron and Shelley, however, [Karl Marx] declared that those who loved and understood these two poets must consider it fortunate that Byron died at the age of 36, for had he lived out his full span he would undoubtedly have become a reactionary bourgeois, whilst regretting on the other hand that Shelley died at the age of 29, for Shelley was a thorough revolutionary and would have remained in the van of socialism all his life.” (Karl Marx: The Story of His Life, Harvester Press, New Jersey, 1966, p.504)

Shelley came from an affluent landowning family, his father a Whig MP. Byron’s continued pride in his title and his recognition of the distance separating himself, a peer of the realm, from his friend, a son of the landed gentry, brings home the pressures against Shelley and the fact that he was able to transcend his background.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s childhood and education were typical of his class. But bullied and unhappy at Eton, he was already developing an independence of thought and the germs of egalitarian feeling. Opposed to the school’s fagging system (making younger pupils beholden as servants to older boys), he was also enthusiastically pursuing science experiments.

He was expelled from Oxford in 1811 for publishing a tract titled “The Necessity of Atheism.” That year he also published anonymously an anti-war “Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things.” This was a fundraiser for Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, imprisoned for libel after accusing Viscount Castlereagh of mistreating United Irish prisoners. Long thought lost, a copy was found in 2006 and made available by the Bodleian Library in 2015.

Ireland was a pressing concern. Shelley visited Ireland between February and April 1812, and his “Address to the Irish People” from that year called for Catholic emancipation and a repeal of the 1800 Union Act passed after the 1798 rebellions. Shelley called the act “the most successful engine that England ever wielded over the misery of fallen Ireland.”

Shelley’s formative radicalism was informed by the French Revolution. That bourgeois revolution raised the prospect of future socialist revolutionary struggles, the material basis for which—the growth of the industrial working class—was only just emerging.

Many older Romantic poets who had, even ambivalently, welcomed the French Revolution as progressive reacted to its limitations by rejecting further strivings for liberty. Shelley denounced this, writing of William Wordsworth in 1816:

In honoured poverty thy voice did weave

Songs consecrate to truth and liberty, —

Deserting these, thou leavest me to grieve,

Thus having been, that thou shouldst cease to be.

In 1811, Shelley visited the reactionary future poet laureate Robert Southey. He had admired Southey’s poetry, but not his politics, writing, “[H]e to whom Bigotry, Tyranny, Law was hateful, has become the votary of those idols in a form most disgusting.” Southey furnished Shelley with his introduction to William Godwin, whose daughter Mary would become Shelley’s wife.

Mary Shelley, 1849, Richard Rothwell

Godwin’s anarchism reflects the utopianism of a period before the emergence of a mass working class, although his novel Caleb Williams (1794) remains powerful. Shelley learned from Godwin, but was also attuned to social, political and technological developments.

Shelley’s 1813 philosophical poem Queen Mab, incorporating the atheism pamphlet in its notes, sought to synthesise Godwin’s conception of political necessity with his own thinking about continuing changes in nature. Where some had abandoned ideas of revolutionary change because of the emergence of Napoleon after the French Revolution, Shelley strove to formulate a gradual transformation of society that would still be total.

He summarised his views on the progress of the French Revolution in 1816, addressing the “fallen tyrant” Napoleon:

I did groan

To think that a most unambitious slave,

Like thou, shouldst dance and revel on the grave

Of Liberty.

He concluded:

That Virtue owns a more eternal foe

Than Force or Fraud: old Custom, legal Crime.

And bloody Faith the foulest birth of Time.

This was a statement of continued commitment to radical change and an overhaul of society. Queen Mab’s radicalism was recognised and feared. In George Cruikshank’s 1821 cartoon, “The Revolutionary Association,” one placard reads “Queen Mab or Killing no Murder.”

Eleanor Marx (middle) with her two sisters - Jenny Longuet, Laura Marx, father Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

What marks Shelley as revolutionary is his ongoing assessment of political and social developments. He was neither politically demoralised by the trajectory of the French Revolution nor tied to outmoded ways of thinking about it. He was able to some extent to carry the utopian revolutionary optimism forward into a period that saw the material emergence of the social force capable of realising the envisaged change, the working class.

His commitment to revolutionary change was “more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract,” as Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling wrote in 1888. It was a concrete striving that had to find direct political expression.

This is what makes Shelley’s response to Peterloo significant. Hearing the “terrible and important news” he wrote, “These are, as it were, the distant thunders of the terrible storm which is approaching. The tyrants here, as in the French Revolution, have first shed blood. May their execrable lessons not be learnt with equal docility!”

He began work immediately on a series of poems and essays, which he intended to be published together. In The Masque of Anarchy: Written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester, he identified Murder with “a mask like Castlereagh,” (Lord Castlereagh, the leader of the House of Commons, responsible for defending government policy), Fraud as Lord Eldon, the lord chancellor, and Hypocrisy (“Clothed with the Bible, as with light, / And the shadows of the night”) as Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth. The poem’s Anarchy is “God, and King, and Law!” Shelley’s “Anarchy we are all so afraid of is very present with us,” wrote Marx and Aveling, “[A]nd let us add is Capitalism.”

Its 91 stanzas are a devastating indictment of Regency Britain and the poem’s ringing final words—regularly trotted out by Labour leaders, with current party leader Jeremy Corbyn adapting its last line as his main slogan—still reads magnificently despite all such attempts at neutering:

And that slaughter to the Nation

Shall steam up like inspiration,

Eloquent, oracular;

A volcano heard afar.

And these words shall then become

Like Oppression’s thundered doom

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again—again—again—

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number—

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

Shelley was not making holiday speeches. The shaking off of chains is found across the Peterloo poems, and Shelley was grappling with how this might be achieved. In the unfinished essay “A Philosophical View of Reform” he tries to understand the sources of political oppression and the obstacles to its removal. There are indications he was moving away from the gradualism of Queen Mab—“[S]o dear is power that the tyrants themselves neither then, nor now, nor ever, left or leave a path to freedom but through their own blood.”

This is a revolutionary appraisal.

Shelley saw the poet’s role in that process. In the “Philosophical View,” he advanced the position, “Poets and philosophers are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” He later incorporated this into “A Defence of Poetry” (1820), explaining, “[A]s the plowman prepares the soil for the seed, so does the poet prepare mind and heart for the reception of new ideas, and thus for change.”

The Peterloo poems adopt various popular forms and styles. Addressing a popular audience with his attempt at a revolutionary understanding suggests a sympathetic response to the emergence of the working class as a political force, and the poems are acute on economic relations. As Marx and Aveling said: “…undoubtedly, he knew the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution.” In Song to the Men of England( 1819), he asked:

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

Those rich robes your tyrants wear?

Leigh Hunt; portrait by Benjamin Haydon

Shelley sent the collection to his friend Leigh Hunt’s journal, but Hunt did not publish it. Publication would, of course, have inevitably resulted in prosecution, although other publishers were risking that. When Hunt did finally publish The Mask of Anarchy in 1832, he justified earlier non-publication by arguing that “the public at large had not become sufficiently discerning to do justice to the sincerity and kind-heartedness of the spirit that walked in this flaming robe of verse.”

Advanced sections of the working class, however, understood the poems as they were intended. Shelley’s poetry was read and championed by a different audience than Hunt’s radical middle class.

As Friedrich Engels wrote in 1843 to the Swiss Republican newspaper: “Byron and Shelley are read almost exclusively by the lower classes; no ‘respectable’ person could have the works of the latter on his desk without his coming into the most terrible disrepute. It remains true: blessed are the poor, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven and, however long it may take, the kingdom of this earth as well.”

The next major upsurge of the British working class, Chartism, drew explicitly on Shelley’s inspiration and work. The direct connection between the generation of Peterloo and the Chartists, many of whom were socialists, found a shared voice in the works of Shelley.

Manchester Hall of Science, c. 1850 (formerly toe Owenite Hall of Science).

Engels continued:

While the Church of England lived in luxury, the Socialists did an incredible amount to educate the working classes in England. At first one cannot get over one’s surprise on hearing in the [Manchester] Hall of Science the most ordinary workers speaking with a clear understanding on political, religious and social affairs; but when one comes across the remarkable popular pamphlets and hears the lecturers of the Socialists, for example [James] Watts in Manchester, one ceases to be surprised. The workers now have good, cheap editions of translations of the French philosophical works of the last century, chiefly Rousseau’s Contrat social, the Système de la Natureand various works by Voltaire, and in addition the exposition of communist principles in penny and twopenny pamphlets and in the journals. The workers also have in their hands cheap editions of the writings of Thomas Paine and Shelley. Furthermore, there are also the Sunday lectures, which are very diligently attended; thus during my stay in Manchester I saw the Communist Hall, which holds about 3,000 people, crowded every Sunday, and I heard there speeches which have a direct effect, which are made from the special viewpoint of the people, and in which witty remarks against the clergy occur. It happens frequently that Christianity is directly attacked and Christians are called ‘our enemies.’” (ibid.)

Richard Carlile published Queen Mab in the 1820s, and pirated editions produced by workers led to it being called a “bible of Chartism.”

Chartist literary criticism provides the most moving and generous testament to Shelley’s legacy in the working class. The Chartist Circular (October 19, 1839) said Shelley’s “noble and benevolent soul…shone forth in its strength and beauty the foremost advocate of Liberty to the despised people,” seeing this in directly political terms: “He believed that, sooner or later, a clash between the two classes was inevitable, and, without hesitation, he ranged himself on the people’s side.”

Friedrich Engels in his early 20s.

Engels was a contributor to the Chartist Northern Star, which had a peak circulation of 80,000. In 1847, Thomas Frost wrote in its pages of Shelley as “the representative and exponent of the future…the most highly gifted harbinger of the coming brightness.” Where Walter Scott wrote of the past, and Byron of the present, Shelley “directed his whole thoughts and aspirations towards the future.” Shelley had summed up that revolutionary optimism in Ode to the West Wind (1820): “If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?”

Shelley found his champions in the working class, quite rightly, so it is worth concluding with the stanza Frost quoted from Revolt of Islam (1817) as a marker of what should be championed in Shelley’s work, and the continued good reasons for reading him today:

This is the winter of the world;—and here

We die, even as the winds of Autumn fade,

Expiring in the frore and foggy air.—

Behold! Spring comes, though we must pass, who made

The promise of its birth—even as the shade

Which from our death, as from a mountain, flings

The future, a broad sunrise; thus arrayed

As with the plumes of overshadowing wings,

From its dark gulf of chains, Earth like an eagle springs.

Professor Michael Demson on the Real-World Impact of Shelley's Writing. A Summary by Jonathan Kerr.

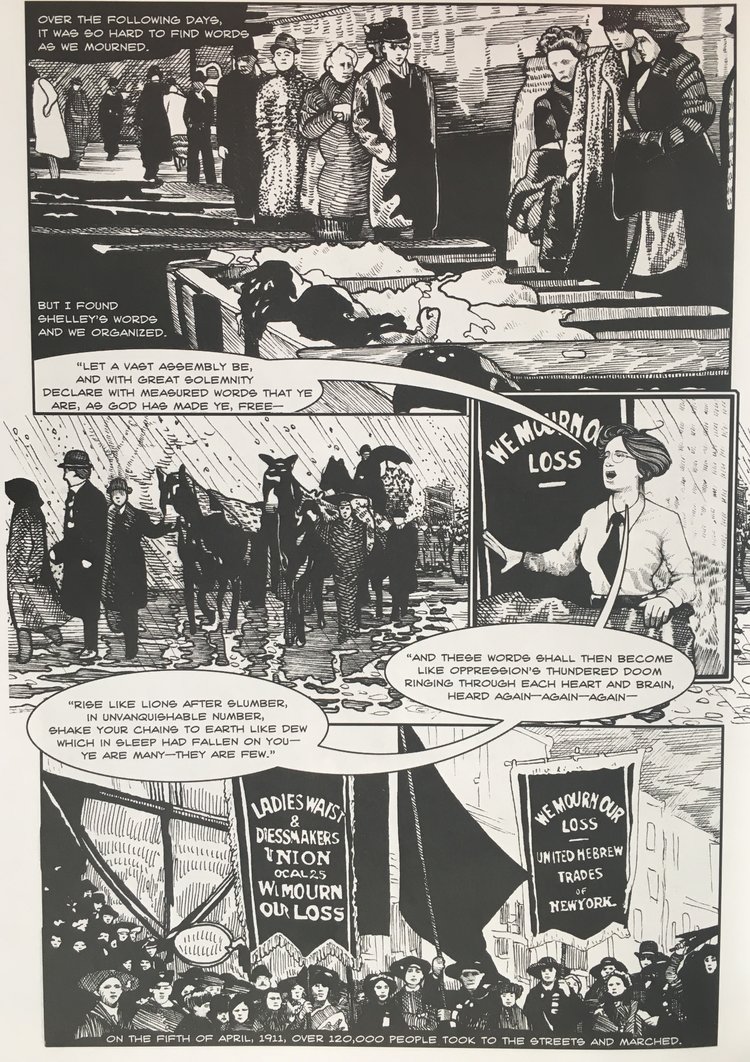

Shelley’s poetry, Michael Demson argues, gave American workers a kind of writing that helped them to understand the political and economic forces to which they were subjected. “The Mask of Anarchy” was especially important in this context: written in easy-to-understand language, this poem attacks the power imbalances that helped to keep the powerful empowered and the poor disenfranchised. The conditions that made this sort of thing possible when Shelley lived—corrupt legal systems, unequal access to education, and working conditions that kept labourers underpaid and vulnerable—remained largely unchanged a century later in America. This is why, Demson alleges, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” could act as such a catalyzing force for New York’s industrial workers, not only providing common people with a language for understanding their problems, but also helping them to build a sense of community.

Michael Demson, “‘Let a great Assembly be’: Percy Shelley’s ‘The Mask of Anarchy,’” published in The European Romantic Review, Volume 22, Number 5, p. 641-665

a précis by Jonathan Kerr.

In “‘Let a great Assembly be,'” Michael Demson unearths powerful evidence for the real-world impact of Shelley’s writing. Many literary scholars throughout history have dismissed Shelley’s politics as naïve, out-of-touch, or disingenuous, a kind of adolescent posturing. By contrast, Demson not only reasserts Shelley’s deep commitment to radical causes; he also demonstrates that Shelley’s political poetry had concrete social impact in the decades and centuries following the poet’s death. Far from an elite writer speaking only to learned readers, Shelley used his poetry to expose and redress problems afflicting everyday people—and this effort paid off.

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), whose labour activism was influenced by Shelley's writing.

Demson makes his case by investigating the role Shelley’s writing played in America’s early twentieth-century unions, and New York’s International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in particular. Shelley’s poetry, Demson argues, gave American workers a kind of writing that helped them to understand the political and economic forces to which they were subjected. “The Mask of Anarchy” was especially important in this context: written in easy-to-understand language, this poem attacks the power imbalances that helped to keep the powerful empowered and the poor disenfranchised. The conditions that made this sort of thing possible when Shelley lived—corrupt legal systems, unequal access to education, and working conditions that kept labourers underpaid and vulnerable—remained largely unchanged a century later in America. This is why, Demson alleges, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” could act as such a catalyzing force for New York’s industrial workers. In Demson’s words, “the language of ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ became the common tongue among workers, not only articulating their miserable conditions in a manner that brought them together, but also providing the terms of and for their protest” (651). As Demson suggests here, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” not only offered common people a language for understanding their problems, but also helped workers to build a sense of community from culture and shared political goals.

Pauline Newman (), whose labour activism was influenced by "The Mask of Anarchy."

No figure in New York’s labour movement was more influential than Pauline Newman (1887-1986) for organizing workers and forcing workplace reform. At the same time, no writer was more important to Newman’s efforts than Percy Shelley. Newman, born in modern-day Lithuania to Jewish parents, fought anti-Semitic and misogynistic laws in her home country and America to win herself an education; following the Newmans’ move to New York City’s Lower East Side, she worked at several factories in order to help her family stay afloat; in fact, Newman was just nine years old when she took her first job. This experience gave her a first-hand understanding of the dismal conditions afflicting lower-class workers. As she worked long hours in New York’s factory grind, Newman taught herself English and quickly became interested in Socialism. While still in her early twenties, Newman rose to prominence as an organizer for the ILGWU, helping to lead the cause toward unionization in America’s blue-collar industries. It was around this time that Newman also became introduced to Shelley’s writing by an English professor at New York’s City College.

As Demson shows, Newman believed that true change for workers required not only new laws and systems of regulation, but education and literacy: these were the tools required for achieving a cultural (and not merely legislative) sea change. Newman helped to organize union reading groups that brought workers (and particularly female workers) together. Shelley was an especially popular author for these reading groups. This is because poems like “The Mask of Anarchy” addressed the major problems affecting labourers in Shelley’s time and in Newman’s: low pay, dangerous working conditions, and degrading treatment by employers. But by bringing people together through culture, Demson argues, Shelley also inspired class pride and even helped to build bridges between New York’s immigrant populations.

Pauline Newman was not the only influential unionist who championed Shelley. Demson points out that Shelley’s writings were also extremely popular subjects of study at the Workers’ University, an institution founded in 1918 by the ILGWU. Demson writes that “Shelley’s poetry was taught at the… Workers’ University to hundreds of laborers as the first poet in history to voice their struggles” (646). This helped to build the growing image of Shelley as a poet of the people, and his writings increasingly acted as a source of education, community-building, and protest for workers across America. Shelley’s influence on these circles of labour organizers and reformers leads Demson to a powerful conclusion: “‘The Mask of Anarchy’ played a very real role to bring about substantive change in the… realities of countless laborers in a time of political crisis” (646).

Cell from Michael Demson's, Masks of Anarchy

Demson argues that Shelley was not writing primary for the downtrodden of his own time: rather, “Shelley may have conceived of the reception of ‘The Mask of Anarchy,’ and his commitment to reform, in a larger… historical framework” (644)—that is to say, when Shelley wrote, he may have had in mind future communities of readers, taking up his revolutionary call generations after his own death. Shelley’s readers in the workers’ unions and universities explored by Demson answered such a call. As they did so, they confirmed Shelley’s view that the truth of a work like “The Mask of Anarchy” means that its power will be felt not only in its own time, but in the decades and centuries after.

Want more? In Masks of Anarchy, a graphic novel published by Verso Books, Demson gives us a fictionalized account of how Shelley’s great poem inspired reformers and changed history. You can find it at local book stores everywhere; you can also find more about Demson’s novel here.

Jonathan Kerr has recently obtained his PhD in English from the University of Toronto. His research explores changing ideas about nature and human nature in the writings of Shelley and his contemporaries. He is currently at Mount Alison University on a post doc.

Keats’s Ode To Autumn Warns About Mass Surveillance

John Keats’s ode To Autumn is one of the best-loved poems in the English language. Composed during a walk to St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, on September 19 1819, it depicts an apparently idyllic scene of harvest home, where drowsy, contented reapers “spare the next swath” beneath the “maturing sun”. The atmosphere of calm finality and mellow ease has comforted generations of readers, and To Autumn is often anthologised as a poem of acceptance of death. But, until now, we may have been missing one of its most pressing themes: surveillance.

Introduction.

In his wonderful graphic novel, Masks of Anarchy (reviewed by me here) Professor Michael Demson offers a glimpse into the sort of surveillance ("spying") to which Shelley was subjected. His letters were read, he was followed, he was the subject of specific investigatiuons authorized by Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary who presided of England's massive spying apparatus. Sidmouth was an arch-conservative figure in the Georgian period. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

As home secretary in the ministry of the earl of Liverpool, from June 1812 to January 1822, Sidmouth faced general edginess caused by high prices, business failures, and widespread unemployment. To crush demonstrations both by manufacturers and by Luddites (anti-industrial machine-smashing radicals) he increased the summary powers of magistrates. At his insistence the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended in 1817, and he introduced four of the coercive Six Acts of 1819, which, among other provisions, limited the rights of the people to hold public meetings and to circulate political literature.

These measures are among the most draconian anti-democratic measures ever enacted by an English government. It is easy to see why Shelley fell afoul of the authorities. From a very young age he was constantly and openly rebelling against the government and social conventions of the day. Much of his prose and poetry explicitly reacts to actions taken by Lord Sidmouth and in fact Lord Sidmouth is one of the three named agents of Anarchy in the Mask of Anarchy:

Clothed with the Bible, as with light, / And the shadows of the night, / Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy / On a crocodile rode by. And many more Destructions played / In this ghastly masquerade, / All disguised, even to the eyes, / Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

Shelley learning of Peterloo. Imagined by Michael Demson in Masks of Anarchy. Buy it here.

Note the specific reference to spies here. This now famous poem, which had enormous political influence over succeeding generations, was never published in his life time - directly as a consequence of laws enacted by Lord Sidmouth. PMS Dawson and Kenneth Neill Cameron (among others) offer penetrating insights into the effect this had on Shelley. He came to the attention of the authorities very early thanks to his visit to Ireland in 1812 (when he was 20) to support the cause of separation and the repeal of the Act of Union. A trunk of his, containing letters and copies of his Address to the Irish People, was detained at the border and forwarded to the Home office where its contents were inspected by Lord Sidmouth who personally authorized the surveillance of Shelley. Shelley never once stopped publishing (or attempting to publish) excoriating critiques of the government. For example: Letter in Defence of Richard Carlile, A Proposal for Putting Reform to the Vote, An Address to the People on the Death of the Princess Charlotte and A Philosophical View of Reform.

The effect of the government's attention however made Shelley fearful and at times even (justifiably) paranoid. It is surely one of the principle reasons he went into a self-imposed exile in Italy. If we do not understand just how pervasive and intrusive government surveillance was during this period, we cannot understand the poets and essayists of the time.

Richard Marggraf Turley (see below) has now offered a tantalizing, penetrating and brilliantly written insight into the effect of Lord Sidmouth's repressive laws on another famous poet of the period: John Keats. Keats reacted to the government's mass surveillance in a very different way, and I will turn it over now to Richard to tell the story.

Keats’s Ode To Autumn Warns About Mass Surveillance and Social Sharing.

by Richard Marggraf Turley

Richard Marggraf Turley. Photo: Sara Penrhyn Jones

John Keats’s ode To Autumn is one of the best-loved poems in the English language. Composed during a walk to St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, on September 19 1819, it depicts an apparently idyllic scene of harvest home, where drowsy, contented reapers “spare the next swath” beneath the “maturing sun”.

The atmosphere of calm finality and mellow ease has comforted generations of readers, and To Autumn is often anthologised as a poem of acceptance of death. But, until now, we may have been missing one of its most pressing themes: surveillance.

The opening of the second stanza appears to be a straightforward allusion to personified autumn: “Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?” But that negative is odd, and hints at a more troubling side to the famous poem. Keats, a London boy, was walking in Winchester’s rural environs to get away from it all – but rather than describing a peaceful stroll, the poem seems to form an anxious meditation on the impossibility of privacy.

St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, in 2010. Peter Trimming/Geograph.org, CC BY-SA

Seen thee

We might assume mass surveillance is a modern phenomenon, but “surveillance” is a Romantic word, first introduced to English readers in 1799. It acquired a chilling sub-entry in 1816 in Charles James’s Military Dictionary: the condition of “existing under the eye of the police”.

But why would Keats have been thinking about spies in the St Giles cornfield? Rewind six days to September 13, 1819, when Henry “Orator” Hunt was entering London to stand trial for treason.

The political reformer had been arrested in Manchester for speaking at the Peterloo Massacre. Hunt was welcomed to the capital by a crowd of 300,000, with Keats, whose literary circle included political radicals, among those lining the streets to catch a glimpse of the government’s greatest bugbear.

London was on lock down. The Bank of England had closed its doors, the entrance to Mansion House was packed with constables and the artillery was on standby. Spies mingled with the Orator’s supporters, listening out for murmurs of popular uprising.

These were dangerous times, which To Autumn perhaps acknowledges with its opening allusion to close conspiracy and loading (weapons): Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun / Conspiring with him how to load and bless / With fruit …

Usually a garrulous letter writer, Keats waited until September 18 – the day before he wrote his ode – to describe Hunt’s procession to his brother and sister-in-law, and then in only the sketchiest terms. He notes the huge numbers but carefully distances himself from the cheering crowds, claiming it had taken him all day to feel “among men”.

Keats is uncharacteristically circumspect, almost as if he feared his correspondence might be intercepted – and perhaps for good reason.

Keats posted two letters during Hunt’s pageant, to his fiancé Fanny Brawne, and to his friend Charles Brown. The first letter arrived without mishap, but Brown’s went missing for 11 days. Later, Keats told him he believed the letter “had been stopped from curiosity” – that is, read by third parties.

The Massacre of Peterloo. George Cruikshank/Wikimedia

The truth was more mundane: Keats had got Brown’s address wrong, and the missive duly turned up on September 24. The letter has since been lost, and we can only guess at its contents, but it’s not inconceivable that, in the midst of Hunt’s maelstrom, Keats had been more candid about his support for the “hero of Peterloo”.

What we do know is that when Keats was writing his great ode on September 19, he suspected his private correspondence, posted during one of the most controversial political marches of the age, was in the hands of government spies.

Spies and informers

Keats’s creative antennae were already attuned to the issue of surveillance before this incident. His long poem Lamia, finished that same September, describes its heroine being tracked through the streets of Corinth by “most curious” spies (compare the phrase Keats used to refer to his missing letter: “stopped from curiosity”). That poem opens with a queasy scene in which Hermes transforms Lamia from serpent to woman. The price is information: Lamia agrees to give up the location of a nymph’s “secret bed” to the priapic god.

A rosy-hued Winchester cornfield might seem a long way from buzzing Corinth, or the violent scenes at Peterloo, or indeed the convulsed capital itself. But the field’s apparent calm is actually a fault line in Keats’s supposedly idyllic poem: the reapers, whose hooks lie idle, ought to be working flat out.

Landowners often grumbled about the laziness of Hampshire’s (poorly paid) casual labourers. It could be that Keats’s ode unwittingly drops the delinquent reapers in it, the poem’s lens giving them away at their “secret bed” (to recall Lamia’s betrayal of the sleeping nymph).

To Autumn is full of directed acts of invigilation: looking (patiently), watching (hours by hours), and seeking abroad (Keats’s first draft was more ominous: “whoever seeks for thee”). All the while those poor labourers were oblivious to the fact that their furtive nap was being observed, and carefully recorded.

Because let’s not forget, Keats is describing actual workers, real people whose slacking off he reports as unthinkingly as we might share our own peers’ political views or locations on social media. As casually as a Google car might capture a moonlighting worker up a ladder outside someone’s house.

When we take all this into account, To Autumn begins to read as an all-seeing optic, internalising the very surveillance culture Keats worried about, and itself becoming a spy transcript.

The ode is an early example of how art and literature process the psychological impacts of intrusive supervision. Written (in Keats’s mind) under surveillance, and bearing the marks of that imaginative pressure, the poem offers itself as a powerful document of what happens to communities, to social groups – to sociability itself – when watching, informing and being informed on become the norms of human interaction.

Richard Marggraf Turley is an award-winning Welsh writer and critic, author of Wan-Hu's Flying Chair and The Cunning House, as well as books on the Romantic poets. He was born in the Forest of Dean and lives in West Wales, where he teaches English Literature and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University. He is the University’s Professor of Engagement with the Public Imagination. You can find him on Twitter and here on the web. This article was originally published by The Conversation and you can read it here. It is republished here under a Creative Commons Licence and with the permission of the author. Thank you, Richard.

Shelley Lives - Taking the Revolutionary Poet Shelley to the Streets.

Last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. Read his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience. I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. The revolutionary Shelley would be ecstatic!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing on my site: The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. Mark Summers came late to Shelley - he first encountered him when the newly discovered Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things was published for the first time in late 2015. But he was a quick learner, and I think he has a better sense of Shelley than many people who have been studying him for thirty years.

Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics and history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller.

Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. What I love most about it is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

One of Mark's dreams was to "take Shelley to the streets". There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Then there was the early 20th Century union organizer Pauline Newman who deployed Shelley's poetry to great effect while founding the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. I wrote about that in Masks of Anarchy by Michael Demson. I also recently reported on a highly unusual but effective use of Shelley's The Mask of Anarchy by English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton: Shelley Storms the Fashion World With Mask of Anarchy.

Well, last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. What follows is his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience - including some very practical ones such as the correct use of a megaphone! I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. It is easy for us to chat amiably about Shelley in seminar rooms or at conferences, to comment on our FaceBook pages or Twitter accounts - it is entirely another thing altogether to go to a protest and read Shelley aloud to demonstrators. Yet this is EXACTLY how I think Shelley would have wanted his poetry to be heard. The closest I have come to Mark's experience pales in comparison: I have taken to working Shelley into all my speeches. And what I have taken away from the experience is very similar to what Mark learned. So grab a coffee or a whiskey (or both) and settle in for a terrific read.

Suits, Poetry and Megaphones; My Experience with Shelley at #TakeBackBrum 2016 - by Mark Summers

In previous posts and articles I have described some of the ways in which the works of the great philosopher and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley have stood the test of time. My central point is that beneath the establishment whitewash, Shelley’s work is as relevant to radical politics now as it was two centuries ago; his concerns are our concerns. So it has been an idea of mine to take Shelley back to where he belongs – the streets of Britain, via a megaphone!

Protest and Poetry

This year the Conservative Party held its annual conference in central Birmingham between the 2nd and 5th October. As a means of protesting the Government’s austerity measures which has seen the poorer and more vulnerable members of society paying for the excess and incompetence of a broken financial system, the People’s Assembly organized a weekend of protest in the city. With our presence at the start of the Sunday protest march, the Birmingham branch of Republic Campaign drew attention to the fact that monarchy is one of the few institutions completely shielded from the cuts inflicted on the rest of society. This presented the perfect opportunity to debut my ‘Street Shelley’ plan especially as between 10,000 and 20,000 people would be queuing up to march past.

Deciding that road transport and parking would be a nightmare I took the train into Birmingham. It was an almost surreal experience as protestors laden with banners, flags and leaflets rubbed shoulders (literally in the case of a crowded train) with conference delegates in suits and carefully coiffured hair!. I had chosen my poems beforehand, England in 1819, Masque of Anarchy and Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things. Three of the most radical and hard hitting of Shelley’s pieces. The major problem I needed to overcome was a total lack of experience of poetry recitation! My original plan had been to include some stanzas from the great chartist poets such as Gerald Massey.

Gerald Massey, Chartist, mid 1850's. From Samuel Smiles' Brief Biographies, 1876.

But powerful as these works are (I must get around to writing about them very soon) they proved far trickier for a novice to handle than the fluid lines of Shelley. Considering the fact that I was also using a megaphone in a restless crowd I decided to play safe by letting the words of the poems do the work.

Learning Quickly

As a shorter sonnet, England in 1819 was suitable for reading in its entirety. But the longer poems needed more careful consideration. One of the delights of reading both Mask of Anarchy and Poetical Essay at your leisure is the way in which Shelley structures his material, diverting now this way, now that way to provide background and develop his theme. This would simply not work for a shifting crowd where the aim is for impact in an environment with competing demands for attention. The best plan would be to choose portions in the hope of hooking people in to discover more. Selecting the material from Mask of Anarchy was a relatively straightforward task with Shelley deftly creating distinct points of tension within its tripartite structure. This means that groups of 10 or 12 stanzas are distributed through the poem which have both internal coherence and impact. So, for example, the following section works as a unit, especially as it contains one the most famous lines in radical poetry "Ye are many—they are few."

Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another ;

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number.

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

…….

[Through to]

……

Paper coin—that forgery

Of the title-deeds, which ye

Hold to something from the worth

Of the inheritance of Earth.

’Tis to be a slave in soul

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

Reciting the poetry was an experience with very steep vertical learning curve. For example, I quickly discovered that it was more effective to actually turn down the megaphone volume and raise the volume of my voice. In this way I realized just how well it works as a visceral language with a weight capable of projection. Lines such as

’Tis to see your children weak

With their mothers pine and peak,

could be delivered with energy and passion, the whole thing becoming quite a cathartic experience. Strangely, despite having spent much time over the past few months with these works I discovered that the meaning of a few words and lines were less obvious than I originally thought.

Image from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, a brilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Shelley Lives!

The reaction of the protestors was mixed. Many of them were simply bemused, but I did draw a small round of applause at one point. More gratifyingly were the people who came up to me and enquired further about the poems which fulfilled a central aim of piquing interest. One person in particular wanted me to place Shelley in the historical sweep of radical dissent. The surprising and depressing fact was that he was an English History graduate for whom radicalism was presented as a half-hearted account of Marxism in the 19th Century! The majestic sweep and variety of radical thought over four centuries had largely passed him by – what an indictment of the education system.

Will I continue – absolutely! The sense of catharsis may have just been simply the result of over-oxygenation of course, but the surge of energy was wonderful. It was also a humbling experience to be a vessel for ideas and emotions far beyond my own abilities to articulate. I felt a great sense of connection, as though the past two centuries had simply evaporated and the man himself was still amongst us. I discovered patterns and connections which had not occurred to me when reading the material quietly and alone. I hope Shelley would have approved of what I had done to his poetry.

For me the work of Shelley is not an artifact to be studied and analyzed but a continuing personal inspiration for my political engagement. I am sure it will be the same for many more people when we release him from the sanitized, gilded cage in which the establishment has trapped him.

Let me tell you something Mark, Shelley, who went to his grave without seeing Mask of Anarchy published, would be overjoyed. Overjoyed because he wrote his poetry to inspire people to change the world the way you have been inspired. But I think his joy would be profoundly tinged with sadness, a sadness which stems from the realization that the world has not changed so very much from his times; the poor are still oppressed, and the rich have grown ever wealthier. Shame on us all.

Mark's article can be found here at his terrific website, New Leveller. It is reprinted with his permission. The banner image at the top of the post comes from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, abrilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. By Mark Summers

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the brink of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing here before. One of Mark's stated goals is to "take Shelley to the streets". I have more to report about this later. There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics/history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller. Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. I first discovered him as a result an article of his which appeared in openDemocracy. I re-published here recently.

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!.

What comes next is Mark's follow-up to his important openDemocracy piece. Mark wrote his article in the summer of 2016; since then Donald Trump was elected President of the United States - making Mark's article prescient and even more compelling. Enjoy!

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet

"Ye are many, they are few!"

The anniversary of two events of primary importance in England's radical history occur in August; the birth of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley on the 4th (in 1792) and the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, England on the 16th (in 1819). Last summer (27 July 2016) my thoughts Shelley’s great Poetical Essay on the State of Things was published on openDemocracy and it is a suitable moment to consider the relevance of another of his great works inspired by events in Manchester, the Mask of Anarchy (you can read it here). Like the openDemocracy article, this post is neither intended as a literary study of Shelley’s work nor an account of the origins of Shelley’s radical opinions. There are many people far better qualified for this task and I can only draw your attention to two examples, Paul Foot’s excellent article from 2006 or the materials on this fascinating blogsite by Graham Henderson. In both my openDemocracy article and the present post I have two aims. Firstly to outline my claim to Shelley as part of the tradition with which I identify and secondly to assess the importance of Shelley’s work and the invaluable lessons it has for us now.

Although popular pressure had been building for reform since the start of the French Revolution in 1789, economic depression and high unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 intensified demands for change. In 1819 a crowd variously estimated at being between 60,000 and 100,000 had gathered in St Peters Field in Manchester to protest and demand greater representation in Parliament. The subsequent overreaction by Government militia forces in the shape of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry led to a cavalry charge with sabres drawn. The exact numbers were never established but about 12 to 15 people were killed immediately and possibly 600-700 were injured, many seriously. For more information on the complex serious of events, go to this British Library resource and this campaign for a memorial. [Editor's note: For more on the Mask of Anarchy, follow this link to my review of Michael Demson's graphic novel, Masks of Anarchy]

Shelley was in Italy when news reached him of the events in Manchester and he set down his reaction in the poem Mask of Anarchy which contains the immortal lines contained in the title of my post. The work simmers over 93 stanzas with a barely controlled rage leading to a call to action and a belief that the approach of non-violent resistance (an approach followed by Gandhi over a century later) would allow the oppressed of England to seize the moral high ground and achieve victory. Such was the power of the poem that it did not appear in public until 1832, the year of the Great Reform Act which extended the voting franchise.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

Anarchy – Chaos and Confusion as a Method of Control

An excellent place to start thinking about the relevance of the poem is with the eponymous evil villain, Anarchy. He leads a band of three tyrants which are identified as contemporary politicians, Murder (Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh), Fraud ( Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon) and Hypocrisy (Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth). But Shelley widens the cast of villains in his description to include the Church, Monarchy and Judiciary.

Last came Anarchy : he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood ;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown ;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone ;

On his brow this mark I saw—

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

The promotion of anarchy with its attendant fear of chaos and disorder was one of the most serious accusations which could be levelled at authority. The avoidance of anarchy was also a concern of English radicals ever since the Civil War in the 1640s and Shelley was making the gravest personal attack with his explicit individual accusations. But Shelley’s attack is pertinent, the implicit threat of confusion and chaos to subdue a population for political ends is something which we experience today. The feeling of powerlessness which can result from an apparently confusing and chaotic situation is something which the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis has termed ‘oh dearism’. In our own time he has identified recent Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne as deliberately using such a tactic. Likewise the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has been variously accused of being a threat to national security or a threat to the economy .

The 1819 Peterloo massacre occurred at a time of heightened external tension with fear that the French revolution would spread to Britain. The fear was not unfounded and various groups around the country emerged with such an intent, in many cases inspired by Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man which the Government had been trying to unsuccessfully suppress. The existence of an external threat combined with homegrown radicals was explicitly used as a reason for a policy of political repression and censorship. Likewise today an external threat, Islamic State combined with an entirely separate perceived internal threat (employee strike action) has been cited as justification for a whole range of measures including invasive communication monitoring (so called ‘Snoopers Charter’) without requisite democratic controls and a repressive Trade Union Bill seeking to shackle the ability of unions to garner support and carry out industrial action.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

The Nature of Freedom

The nature of freedom is a problem which has bothered both libertarians and republicans for generations. In Mask of Anarchy where Shelley is enumerating the injustice suffered by the poor he clearly defines freedom in terms of the state of slavery, a core republican premise:

What is Freedom? Ye can tell

That which Slavery is too well,

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own

The essence of freedom which has financial independence as a core component is clearly articulated over a number of stanzas, starting with:

‘’Tis to work and have such pay

As just keeps life from day to day

In your limbs, as in a cell

For the tyrants’ use to dwell,

‘So that ye for them are made

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade,

With or without your own will bent

To their defence and nourishment.

In our own time freedom is frequently constrained by insufficient financial resources as a result of hardship caused by issues such as disability support cuts, chronic low wages and a zero-hours contract society. Shelley would have no problem with identifying Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley, playing with multi-million pounds football clubs while his workforce toil in iniquitous conditions for a pittance; or Sir Philip Green impoverishing British Home Stores pensioners to pile up a vast fortune for his wife in Monaco.

Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Shelley's Mask of Anarchy is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!.

Non-Violent Resistance – A Way Forward

I pointed out that in the 1811 Poetical Essay, Shelley was searching for a peaceful way to elicit change in an oppressive hierarchical society. By 1819 Shelley has settled on his preferred solution of non-violent resistance.

Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war,

‘And let Panic, who outspeeds

The career of armèd steeds

Pass, a disregarded shade

Through your phalanx undismayed.

Nonviolent resistance is not an instant solution and takes years of persistent and widespread enactment to be successful. A partial victory was secured in the 1830s with the Great Reform Act (1832) and the Abolition of Slavery Act (1834). But history has proved that it is a viable strategy, the independence of India being an eloquent testament.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

This article is republished with the kind permission of the author. It appeared originally on Mark's superb blogsite (www.newleveller.net) on 7 August 2016.

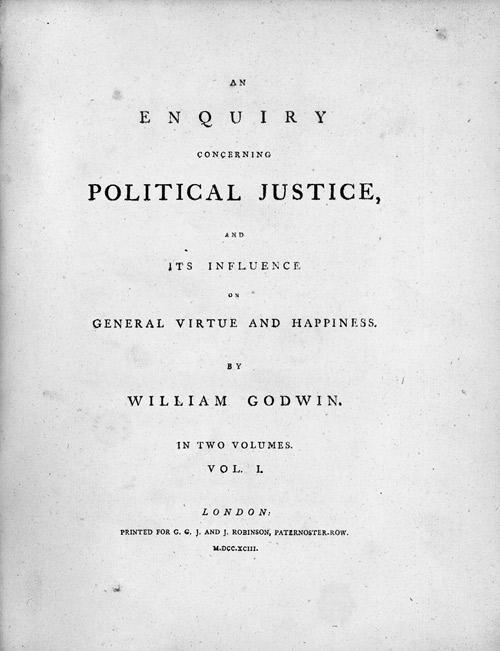

William Godwin: Political Justice, Anarchism and the Romantics

Yet at least in the permanence of the printed word Godwin’s influence on Shelley remains. It is most apparent in Shelley’s political poems, which echo Godwin’s views on the state and his anarchistic vision of society.

Guest Contributors continues with Simon Court's brilliantly concise discussion of William Godwin's influence of the romantic poets. This account contains generous quotes from Godwin himself, and students of Shelley will no doubt hear much of Godwin in Shelley's poetry. But Godwin's influence was not limited to Shelley's political poetry, it can also be seen throughout Shelley's extensive philosophical prose.